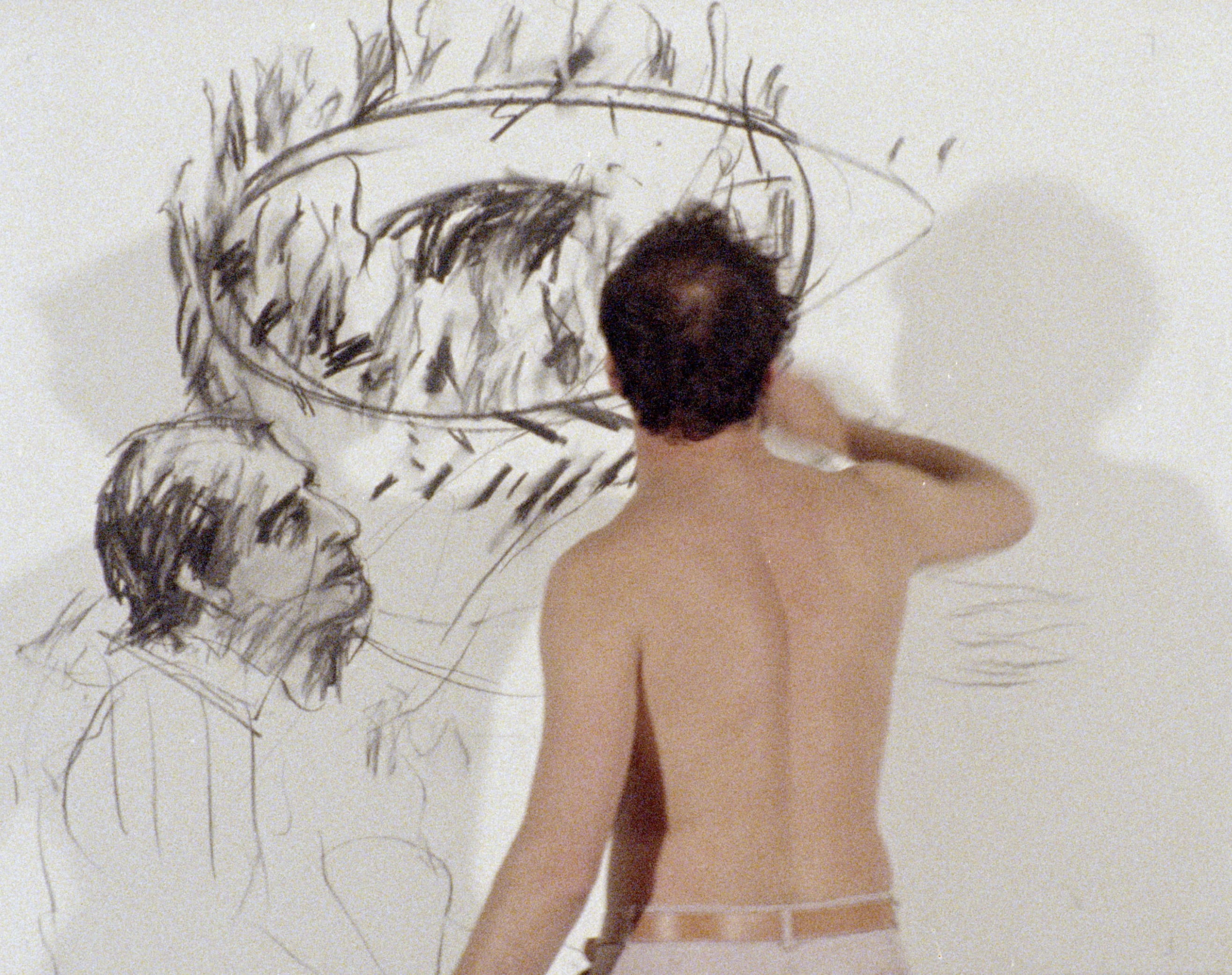

Vetkoek - Fête Galante is a film from the mid-1980s, in a period of the State of Emergency in South Africa – the time preceding the ending of apartheid. It was the first film I made which incorporated fragments of charcoal animation.

I made it using a Bolex 16 millimetre camera that could shoot one frame at a time, which had been lent to me. I set it up in my studio, with one roll of film, and decided that whatever happened in the studio, and whoever entered it whilst I was working on the charcoal drawings, would be included. It was made over a two day period and it records myself, my wife, friends, our daughter Alice, her nanny, her friends, a person who came to the front door asking for food – anybody who was around the house then came into the studio and was filmed.

I showed Vetkoek - Fête Galante to my friend Angus Gibson, who was a film editor, and he pointed out that, in fact, the most interesting thing about it were the animated charcoal drawings. He suggested that I make a film entirely of these charcoal drawings, which at the time was very daunting because it was such a slow way of working. But I took his advice, and that led to the first of the series of ‘Drawings for Projection’, and they all went on from that.

The elements here that continue in all the films that followed on from Vetkoek - Fête Galante were the mixture of text, the masks used in live performance, and, of course, the stop-frame animation.

—William Kentridge, Studio, Johannesburg, October 2021

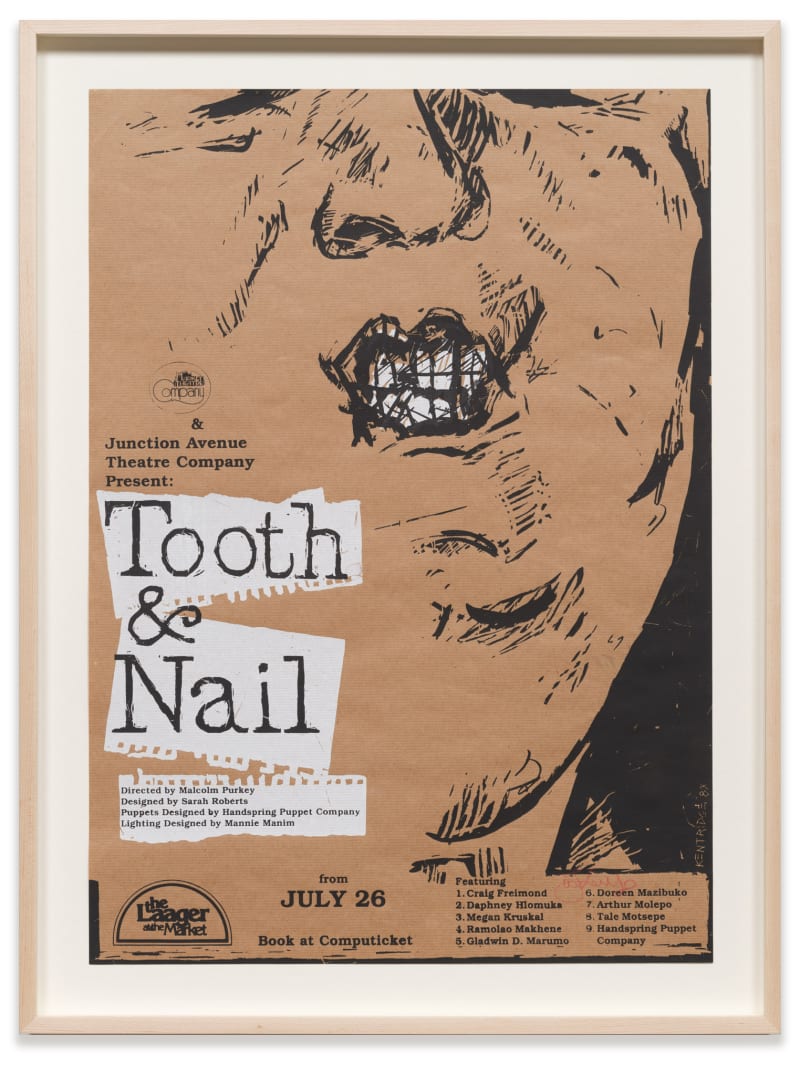

These posters were made in a very simple way: in my studio with a silkscreen, and with a washing line strung across our bedroom and living room. And we'd simply print on a table in the hallway and then hang the prints up to dry with clothes pegs on lines going through our house. These were made with ink and solvents and lacquer thinners - so a toxic atmosphere in which my wife and myself went to sleep every night waiting for them to dry.

I printed these posters, for theatre productions and for small film festivals, on brown paper as a kind of signature of these images which were made. There are very few that actually survived intact.

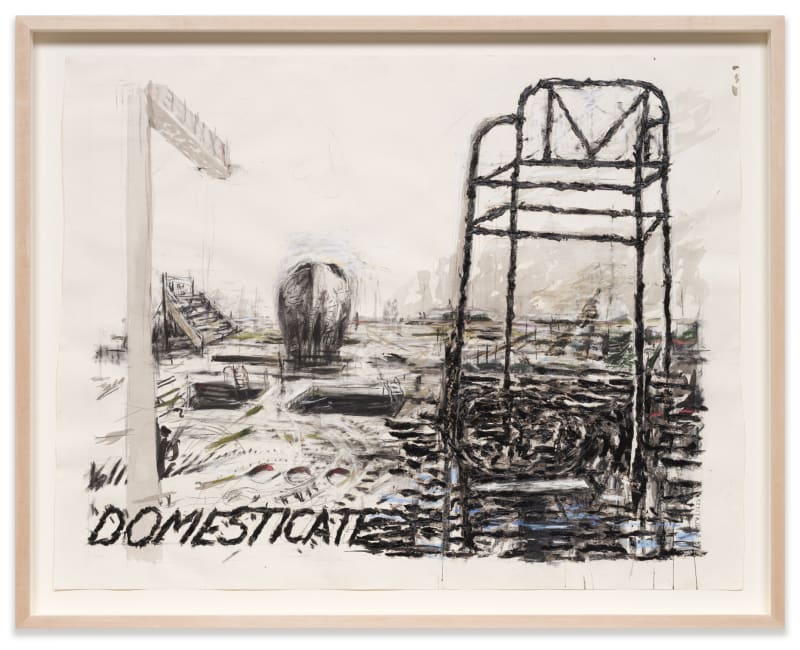

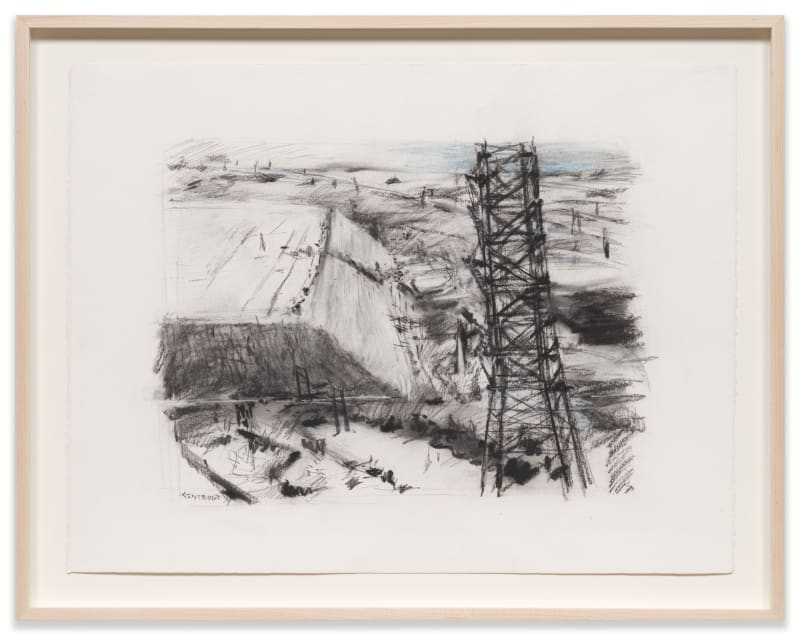

Let Go Scot Free, Domesticate, and East Rand are from a period when I first started drawing the landscape around Johannesburg in 1987. It had come initially as a kind of resistance to the landscape, thinking, this is so different to the traditional landscape, how could it be worth drawing? But when I actually started doing so, there was a great pleasure in understanding the landscape as half-drawn already, full of graphic marks - whether they are a power pylon, an abandoned piece of civil engineering, or the shape of a billboard - they were sort of natural drawings within the landscape. The highveld is very monochromatic, in winter particularly, with harsh sunlight and burnt grass, so it’s a kind of charcoal drawing in nature - a plein air drawing that nature does itself.

It was also a time when I was experimenting with different materials, not quite daring to go into oil paint; I was working with charcoal, bitumen, which is in the Domesticate drawing, and with some gouache, as in Let Go Scot Free.

Let Go Scot Free was made at a time towards the end of apartheid when it seemed that the end result would be that every villain in the entire history of what had happened to people under apartheid would be absolved of their deeds, which, in fact, later on proved to be the case, with the transition to democracy.

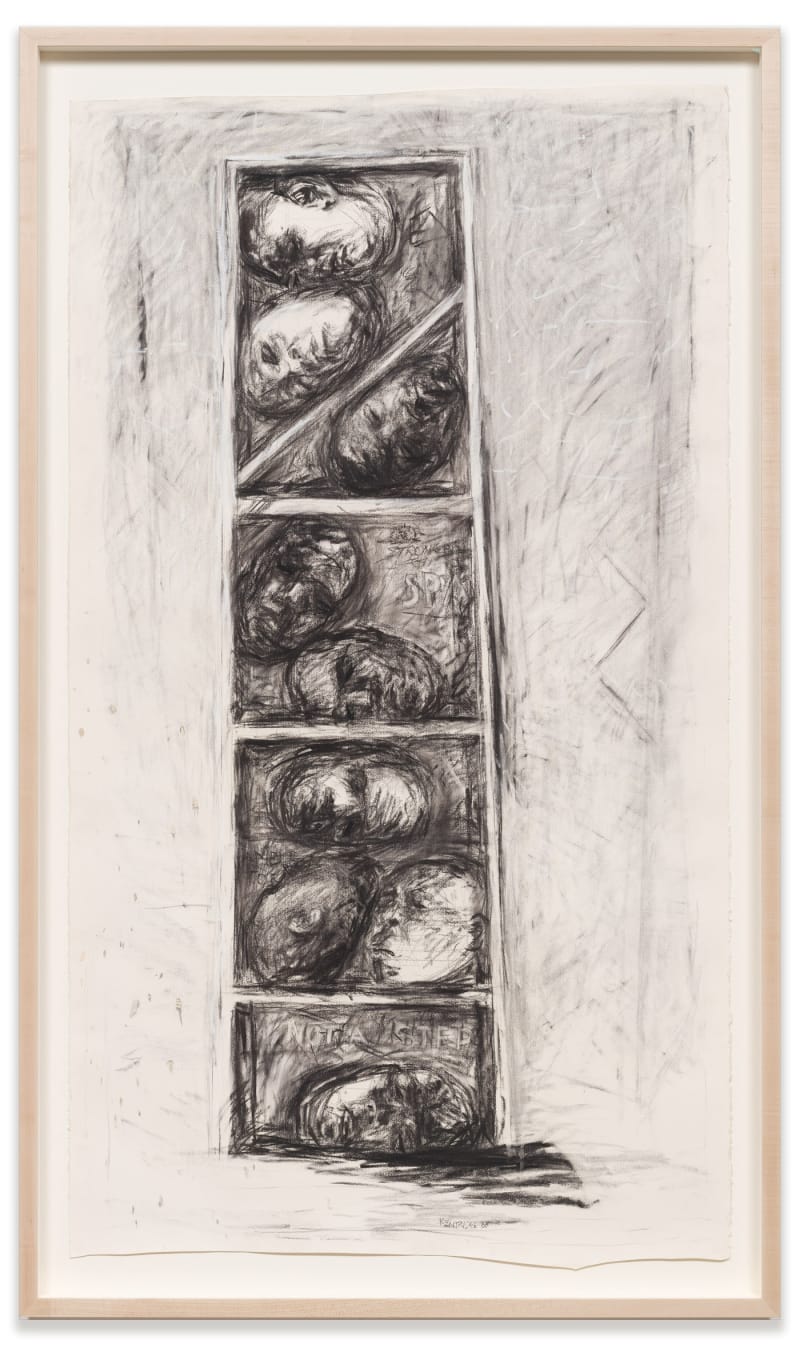

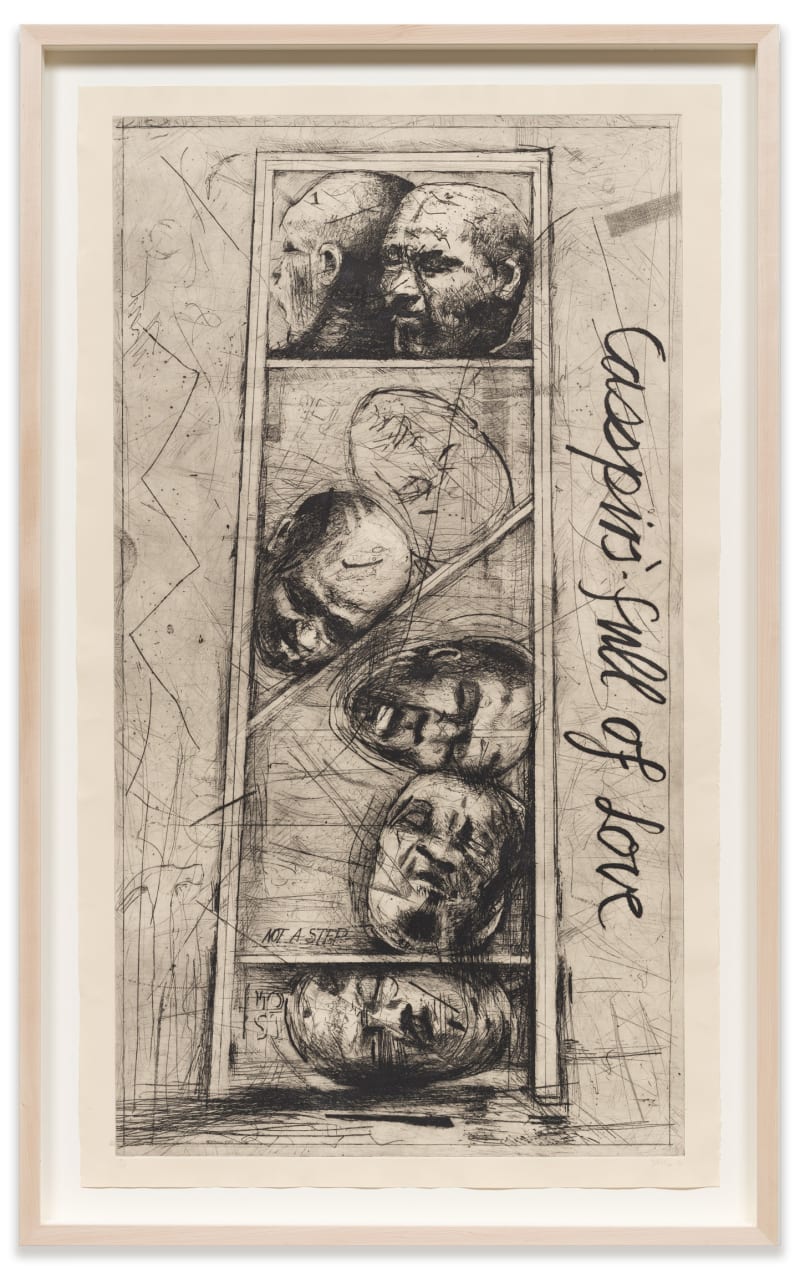

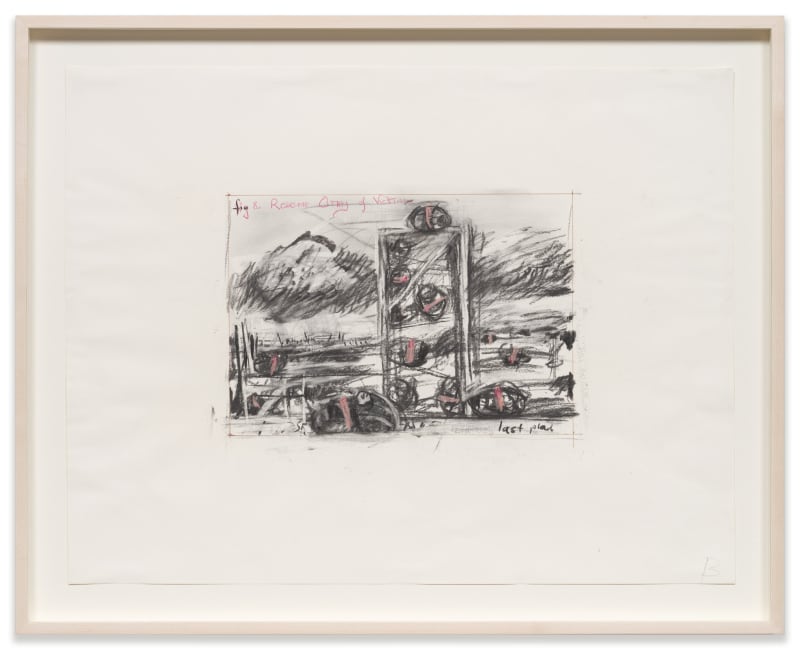

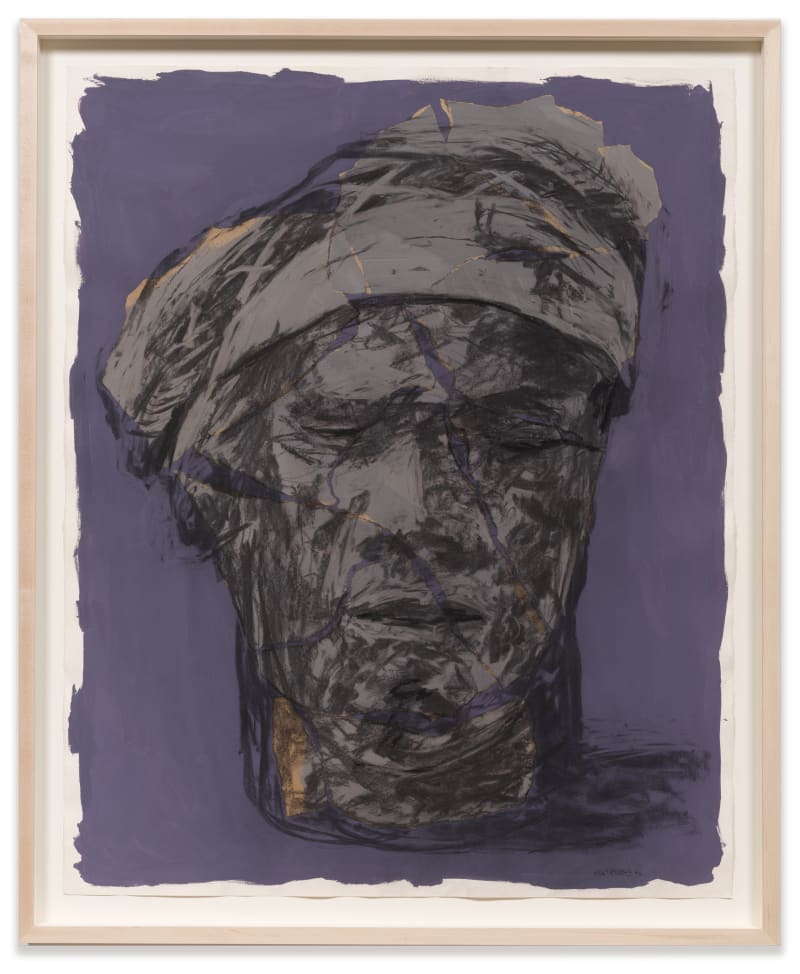

Casspirs Full of Love, the Study for Reserve Army and the Heads are a series of drawings, etchings, silkscreens, and collages that came from the late 1980s and early ’90s, the last years of apartheid in South Africa. They started when I was in Italy for a few months when my wife was on maternity leave: I’d seen some paintings by Giotto in Santa Maria Novella, and had started doing drawings of them when I visited an exhibition of Tony Cragg’s. One of his pieces were casts of beets that had been roughly carved like faces, shown as a pile of heads. Having seen this, I went back to the studio, where I had my drawings of the Giottos, and cut the heads off the saints, then just arranged them into pile, which later became the grouping of heads in their shelves in Casspirs Full of Love.

I’d had that title for a long while: it was from a radio programme called 'Forces Favourites', in which mothers sent messages to their sons serving as conscripts in the South African army. They would usually come with fairly standard messages of, you know, "look after yourself", "longing for you to come home", and so on. But there was one in which a mother sent a message to her son with what she called “Casspirs Full of Love”. A casspir was a military armoured vehicle used by the police and army conscripts against township residents when townships were becoming ungovernable in the period that led to the end of apartheid. And so to have this mixture of these vehicles of violence described as vessels of love was kind of the irony that held me. So, the title was waiting for an image and when these heads were drawn, the image and the title came together.

The Casspirs Full of Love image also makes its way, briefly, into the first of the ‘Drawings for Projection’ films, Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City after Paris, which was made in 1989.

The large Heads were a series of individual charcoal heads drawn on different coloured gouache sheets of paper, painted on brown paper, torn up and rearranged, as a sort of fractured sculpture that had been roughly put back together - kind of heads as ruins. They were based partly on photographs of Ife or Benin Bronzes, and partly on the basis of newspaper photographs of people in the streets of Johannesburg.

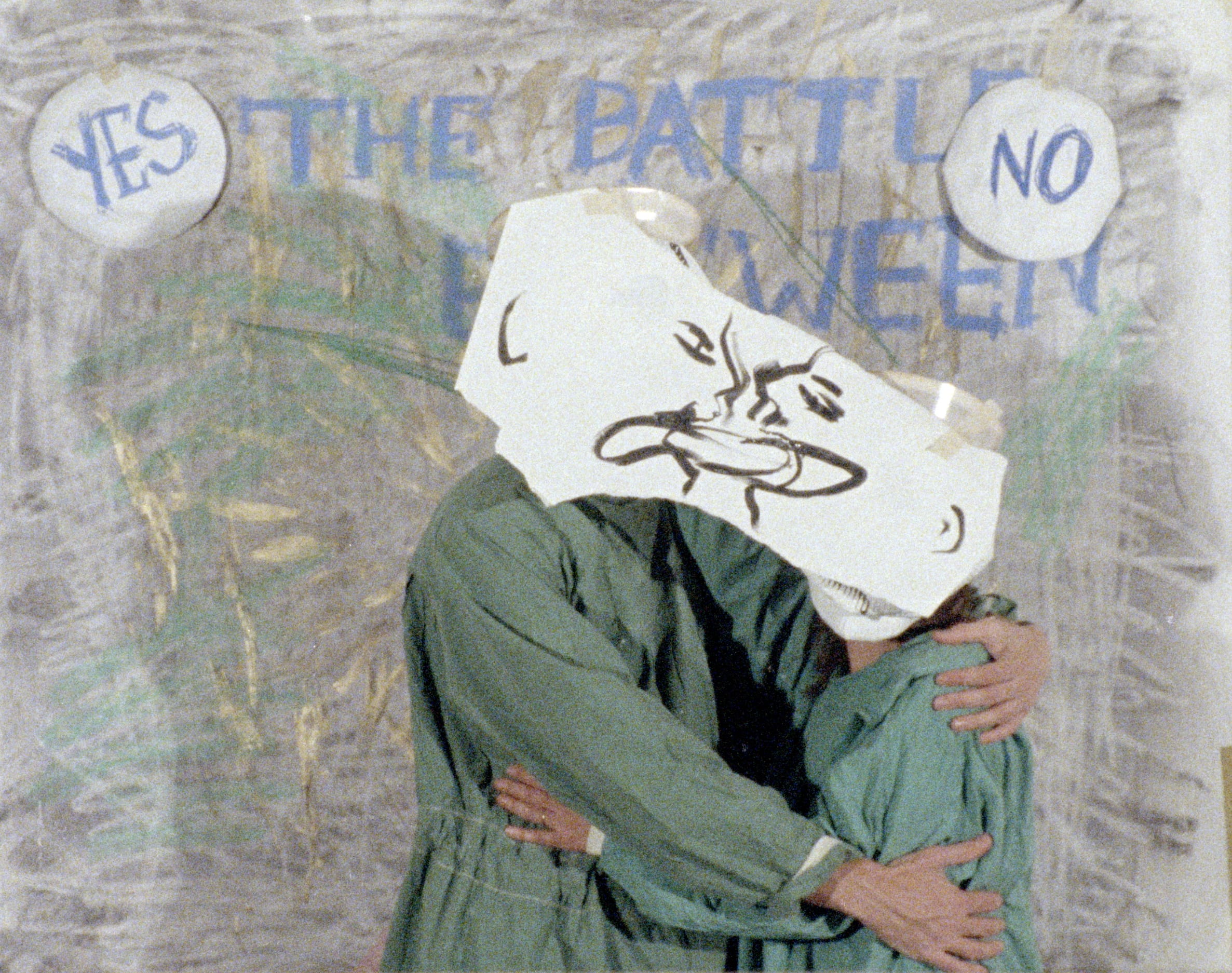

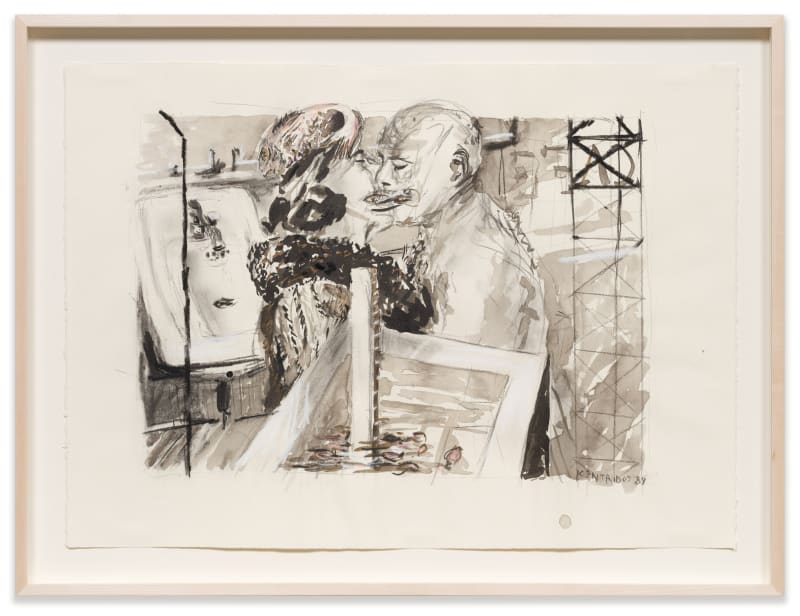

These are a series of images of couples kissing, or almost kissing. They had begun with playing in the film, Vetkoek - Fête Galante, which includes this image of ‘no', ‘yes’ and 'noise'. Of the impossibility of yes and no, of the certainty of either of them, and the world existing somewhere in the chaos between. It is an image of kissing, of tongues in each other's mouths, but also of words not finding their place.

There are many different versions of that on show here, from the animated film, to small drawings, to the large-scale screenprint we made at the Caversham Press in the KwaZulu-Natal part of South Africa.