Rineke Dijkstra

Since the early 1990s, Rineke Dijkstra has produced a complex body of photographic and video work, offering a contemporary take on the genre of portraiture. Her subjects are often caught in a moment of transition. They might be a new soldier at the inception of their career, a young mother following the recent birth of her child, or a young girl growing up in a culture that is unfamiliar to her. By limiting contextual information and focusing on subtle details, such as posture and gaze, Dijkstra encourages the viewer to look closely at her subjects.

"Night Watching,” 2019

The centerpiece of Rineke Dijkstra's first exhibition at the Marian Goodman Gallery in London is the triptych video installation Night Watching, commissioned by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam on the occasion of the 350th anniversary of Rembrandt's death.

Gunners of District II under Captain Frans Banninck Cocq and Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch, known as The Night Watch, 1642, oil on canvas

379.5 cm (12.4 ft) x 453.5 cm (14.8 ft).

Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

Filmed in front of Rembrandt's iconic painting The Night Watch, over the course of six evenings when the museum was closed to the public, Dijkstra invited fourteen diverse groups of people to talk about the artwork's creation, reception, and possible interpretation. What unfolds over thirty-five minutes is one of the most engaging, enlightening, and perceptive artworks about how we look at, talk about, and give meaning to art.

"For Dijkstra, this is a way not only of facing up to Rembrandt, but an exploration of what portraits are really about. We're looking at people looking at people; a nice circularity, she reflects, and a testament to the power and mystery of the form."

– Andy Dickson

In conversation with Rineke Dijkstra, Financial Times, 6 March, 2020

Night Watching was intentionally filmed using different off-set viewpoints, producing a triptych that is not a uniform panorama, to communicate the importance of multiple perspectives and to allow the diversity of Dijkstra’s groups to have full effect. Four Dutch teenage girls chat about whether Rembrandt gave the only woman in the painting the face of his wife Saskia, who died the year the painting was completed. A group of Japanese businessmen consider the painting’s potential for tourism and marketing, especially through Instagram, while their more junior colleagues remain dutifully silent. A group of young artists discuss, with studied intensity, what it must feel like to create a masterpiece that is memorialized in the canon of art history, wondering about the burdens and rewards that might ensue.

When exhibited at the Rijksmuseum in Autumn 2019, Night Watching was presented in a space adjacent to Rembrandt’s painting, offering visitors a direct dialogue with the artwork that remains “off-set” in Dijkstra’s video installation. Night Watching could be seen as a sequel to Dijkstra’s I See A Woman Crying, 2009, a comparable video portrait in which a group of 12-year-old children from a Liverpool primary school look at a work by Picasso. The painting again remains “off-set,” invisible to Dijkstra’s viewer; we observe only the children as they reflect on Picasso’s masterpiece, describe what they see, and react to each other’s observations.

This scenography of the “original,” an incomplete image in our memories, is at the heart of Dijkstra’s practice and philosophy as an artist. A portrait is always separate from the tangible reality of its subject – an image of a person, or group of people, whose emotions and thoughts, pasts and futures, individuality or similarity, are always at one remove from our immediate grasp. Yet, as with Rembrandt’s portraits from four hundred years ago, their subjects can be uncannily present, alive before you, speaking silently but directly. This intimate connection to the past – knowing a moment is gone while feeling it to be a part of the present – permeates Dijkstra’s approach to portraiture.

However, Night Watching is unlike I See A Woman Crying in that it has a substantive structure. By giving screen time to such a variety of groups, from students to accountants, Dijkstra’s Night Watching becomes a series of group portraits – just like The Night Watch itself. And, as the work unfolds, the viewer is drawn ever deeper into the richness and complexity shared by all good group portraits. The first groups in the film speculate about what they are seeing: a dog painted in a vague manner, an intensely lit girl. The groups in the middle of the film link their visual observations to personal reflections. The groups at the end of the film look at the painting from an art-historical perspective; the university students see it in the context of seventeenth-century society, whereas it slowly dawns on the budding artists that a masterpiece is made primarily by parties other than the artist. We realize that the issues raised by Night Watching go far beyond The Night Watch. What connects the members of a group? What aspects of the relationships in a group are visible? What exactly happens when people look at a painting?

In one scene, featuring three Dutch accountants confidently attired in their business suits, the eldest proudly points out his connection to the central protagonist in the painting, Frans Banninck Cocq. He explains how, some years before, he received a medal from the City of Amsterdam for people who made themselves “useful” to the city, named in honor of the seventeenth-century mayor. His colleague, after a slight pause, dryly retorts: “I don’t begrudge you this medal, but… to me, he comes across as an arrogant prick.”

In this witty triangular exchange, the famous painting both elevates and deflates a short conversational joust, demonstrating Dijkstra’s interest in the role of self-reflection in art. Sensitively attuned to the history of Dutch portraiture and to portrait photography, Dijkstra’s Night Watching is its own self-reflexive group portrait. A document of cultural anthropology, it obliquely mirror-images those watching Rembrandt with those observing them. Like the painted figures who seek the light of hope and strength in the shadows of darkness, the viewer becomes part of the psychological terrain that connects Dijkstra’s aesthetic journey to the famous painting.

In Night Watching, we also become distinctly aware that our exchanges are ultimately what create value – our relationships with families and strangers, cultures and histories, desires and needs, as well as our communications through talking or sharing, being present or absent, being remembered or forgotten. In this time of social distancing, requiring us to observe and learn from afar, these ideas around value become particularly meaningful and strikingly apposite.

Family Portraits

"Family portraits have been around for many centuries. They are often made for parents whose children have grown up, left home, and started lives of their own. For the parents, the portrait is a reminder of the old family ties that they treasure. Often, it also represents their desire to preserve and capture those family ties, as a way of protecting them from all the changes ahead. Like a magical shield against time."

– Rineke Dijkstra, March 2020

"When I make a family portrait, I sometimes think of the novel 'The Picture of Dorian Gray' by Oscar Wilde. In that book, the young Dorian Gray makes a wish that he will always remain the way he looks in his portrait. His wish is granted: the real Dorian Gray literally stops aging. Instead, his portrait grows older over time. While Dorian remains the same, the portrait slowly transforms from an attractive young man into a hideous old monster. The portrait takes over the work of changing. But that doesn't make Dorian happy. I think of that book because I am very well aware that the families I portray will go on living with their portraits. Every day, they will see how I depicted them, how they were frozen at a more or less random point in a past that recedes further and further away. Meanwhile, the family has continued to evolve. The differences are barely visible from day to day, and it's the unchanging portrait that makes them conscious of all these changes. The portrait becomes a kind of baseline, a lasting reminder that time goes by and you don't have to fight it. Change is the heart of life, and that's exactly what Dorian Gray forgot.” – Rineke Dijkstra, March 2020

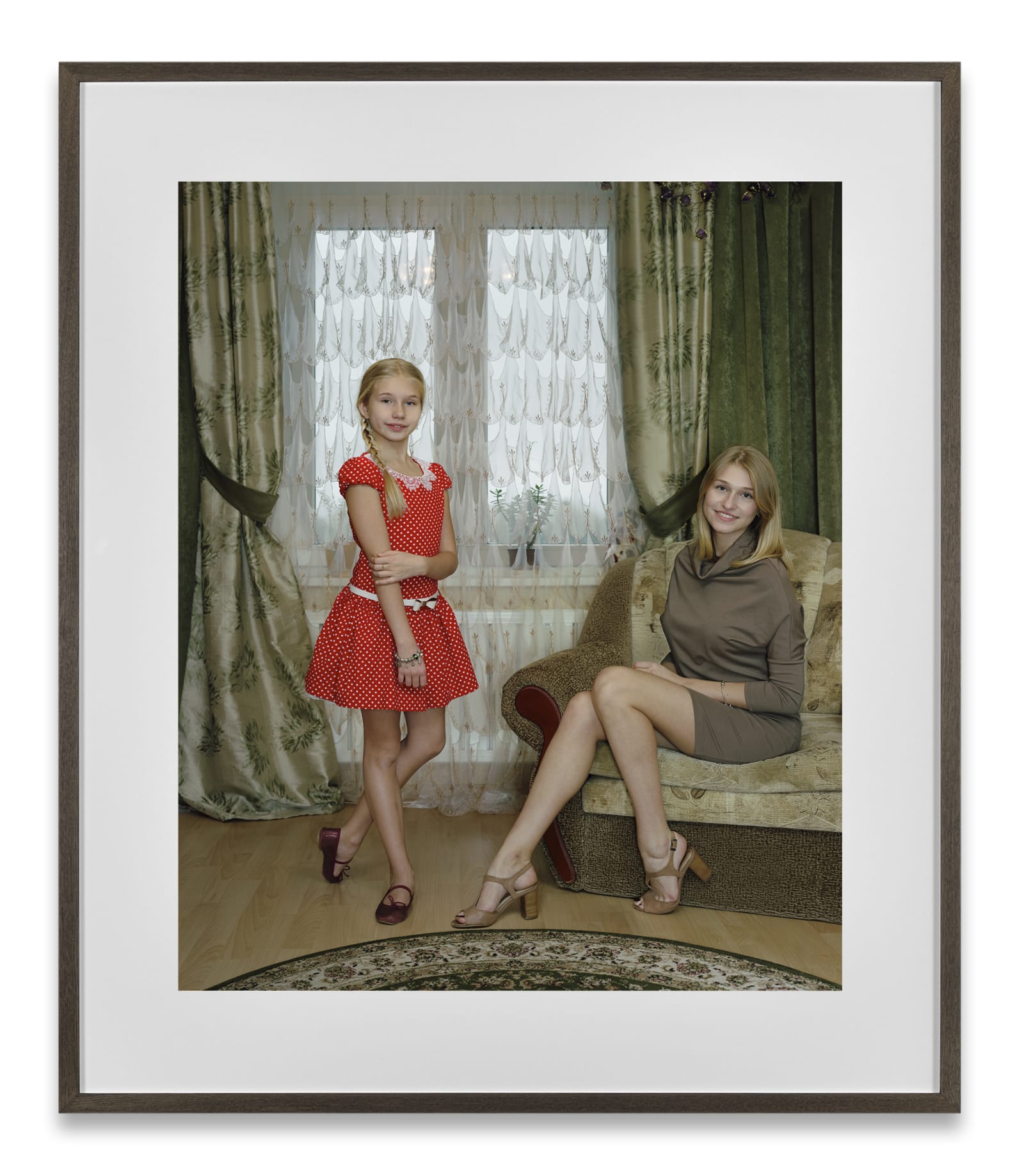

In the main ground floor gallery, the exhibition features eight photographs from Dijkstra’s “Family Portraits” series, which started in 2012 as an ongoing commission project and has since evolved to include families selected by the artist.

Taken within the intimacy of a family home or garden, only one generation of a family is photographed, with neither parents nor grandparents pictured. Comprising portraits of children within their domestic environs, this newer series by Dijkstra develops her longstanding interest in the journey from childhood to adulthood.

For this exhibition, Dijkstra photographed two families living in London, producing Alessandro and Sofia, London, February 9, 2020 and Arden and Miran, London, February 16, 2020.

The children’s names suggest the diversity of London, an international city. Indeed, Alessandro and Sofia are son and daughter of an Italian father and British Sierra Leonean mother, and Arden and Miran are sons of Kurdish parents. More importantly, the settings of the photographs are the children’s homes. In the short time since these photographs were taken, we are now more conscious than ever that one’s home is an intimate and unique space, separated from the world outside. It is in our homes that we take refuge, but equally cultivate our interests, carve out our emotional spaces, and build lives which are uniquely ours.

Employing a wide-format, tripod-based photographic film camera – an analogue technology used in photographic family portraiture for over a century – Dijkstra directs the children to pose with no particular facial expression, to be natural in front of the camera, while being aware that a portrait is being made. Taken in their own spaces and habitats, the resulting images carry both a vulnerability and an assuredness. Dijkstra carefully curates the settings, allowing certain details like pot plants or favorite socks to create nuanced symbolism, reminding us of our own childhood idiosyncrasies and allowing a story to evolve. Two brothers sit together on the same chair, their styles of dress and hair clearly marking their individual personalities and different stages in life.

The youth of Dijkstra’s sitters is often juxtaposed with the formality of their position in spaces defined by the tastes of parents and older family. In Albertine and Andras, Untersiemau, Germany, August 23, 2016, we wonder how these young, barefoot siblings might mature and develop as they sit between different influences and pulses of time: a baroque-style velvet sofa, a classical architectural column, and a contemporary artwork. Their barefoot freedom contrasts with the attired formality of The Grandchildren of Denise Saul, New York, October 15, 2012. Seen together, the works bear witness to two very different forms of imaging, which is less to do with Dijkstra than with the family members outside the frame of the picture.

In Sophie and Alice, Savolinna, Finland, August 3, 2013, two young women look out to meet the lens of Dijkstra’s camera directly. Centered within the frame, one holds a contrapposto stance, traditional to the work of the Italian Old Masters, which can be seen in many of Dijkstra’s portraits; the other sits in a more relaxed manner, with arms on knees. While both are clearly aware they are being photographed, they maintain a neutral expression. Dijkstra has highlighted both the lack of overt intervention and the intensity of gaze that characterizes her approach: “I hardly give any directions and I demand a concentration that is decisive for the photographs.” She is interested in capturing people at moments when their poses have occurred naturally and unconsciously.

As such, Dijkstra’s work recalls an ethnographic style of portraiture reminiscent of photographers working in the 1960s. Yet the luminosity of Dijkstra’s use of color – for example, the dappled light seeping through the tree canopy – enhances the objectivity of this typically cold documentary style of portraiture and recalls the warmth of seventeenth-century Dutch painting. This complex combination of influences on Dijkstra’s approach to portraiture is striking. The inkjet print also has an imposing scale at over fifty inches tall, with the standing figure occupying much of the frame.

The minimal setting contrasts with the specificity of the location disclosed in the artwork’s title: the photograph was taken near the family’s vacation home in Savolinna, a town in the southeast lakeland area of Finland, on August 3, 2013. The sisters are caught in a specific moment in their unfolding personal histories. The wooded steps, upon which they stand or sit, recede into the shadows of the tree canopy to suggest they are poised to journey into adulthood. As a double portrait, the dominating subject is the familial relationship between the sisters, who share a strong resemblance and whose intersecting paths will be both similar and different. Characteristic of Dijkstra’s penetratingly psychological approach to portraiture, the relationship between the pair is also held in play with the relationship between subject and photographer, subject, and viewer.

Commissions

Over the last few years, Rineke has taken on a number of private commissions for family portraits - some of which you can see below. These commissions only portray children or grandchildren and are taken in the family home or garden. If you are interested in finding out more about commissioning Rineke to make a portrait, please contact us here for further details.

Inquire

Parks

In 1998, a decade and a half before she started taking portraits of children in their homes, Dijkstra visited Berlin’s Tiergarten park to photograph children and adolescents at play. Over the next eight years she extended the project to include major parks in Amsterdam, Barcelona, Liverpool, Madrid, Brooklyn (New York), and Xiamen (China).

Parque de la Ciudadela, Barcelona, June 4, 2005

Archival inkjet print

Image: 29 1/2 x 37 in. (75 x 94 cm)

Frame: 42 3/4 x 50 x 1 1/2 in. (108.6 x 127 x 3.8 cm)

Edition of 10

(10160)

Sefton Park, Liverpool, June 10, 2006

Archival inkjet print

Image: 44 5/16 x 55 1/8 in. (112.5 x 140 cm)

Frame: 53 1/4 x 64 x 1 1/2 in. (135.3 x 162.6 x 3.8 cm)

Edition of 10

(11057)

Dijkstra acknowledges, in fact seeks out, the less-than-carefree aspects of a child's development as they mature through adolescence. In Sefton Park, Liverpool, June 10, 2006, a rebellious teenage schoolboy and schoolgirl glower from the shadows as if the artist has interrupted a ritual recalcitrance to which not even their classmates, let alone their teachers, parents, or gallery-goers, should be privy: a private emotional space within a public park.

Outside their homes, the personalities of Dijkstra’s subjects are imbued with the characteristics of the various parks in which she finds them: stage-like, constructed environs that have the nature and form of painterly pastoral settings, or the fairytale associations of the forest. An artist invited into a home has a wholly different relationship with her subjects than a stranger in a park, and it takes a certain type of personality to procure Dijkstra’s attention, then hold their own in this context.

Dijkstra’s use of flash, even in daylight, illuminates subtle details and expressions within the shadows of the trees. Her use of color recalls the warmth and spatial interplay of seventeenth-century Dutch and Spanish painting. In El Parque del Retiro, Madrid, 2006, a young girl stops skipping for just long enough to engage directly with the camera and has all of the presence of a latter-day Las Meninas, recalling the masterpiece that is only a short distance away in the Museo Nacional del Prado.

Durational Works

Throughout her career, Dijkstra has relied on the inherent temporality of photography to explore the changeability of the human condition. This is most evident in her series of portraits that represent the progression of time through an extended durational process, charting equally the progression of the sitter’s relationship with the artist, with her camera, and with us.

A pair of studio portraits depicts Georgie Henley as she transforms from adolescent to young adult, over a period of six years. The diptych communicates how the actor, who became famous as a child in The Chronicles of Narnia, has matured in the public eye into an independent young person.

Chen and Efrat, Israel, 18 Nov. 1999

Archival Inkjet Print

Image: 10 7/8 x 13 5/8 in. (27.6 x 34.6 cm)

Frame: 21 1/2 x 24 x 1 in. (54.6 x 61 x 2.5 cm)

Edition of 10

Set of 5

(7955)

Chen and Efrat, Israel, 16 Dec. 2000

Archival Inkjet Print

Image: 10 7/8 x 13 5/8 in. (27.6 x 34.6 cm)

Frame: 21 1/2 x 24 x 1 in. (54.6 x 61 x 2.5 cm)

Edition of 10

Set of 5

(7954)

Chen and Efrat, Herzliya, Israel, March 4, 2002

Archival inkjet print

Image: 10 7/8 x 13 5/8 in. (27.6 x 34.6 cm)

Frame: 21 1/2 x 24 x 1 5/8 in. (54.61 x 60.96 x 4.13 cm)

Edition of 10

Set of 5

(13138)

Chen and Efrat, Herzliya, Israel, March 27, 2004

Archival Inkjet Print

Image: 10 7/8 x 13 5/8 in. (27.6 x 34.6 cm)

Frame: 21 1/2 x 24 x 1 in. (54.6 x 61 x 2.5 cm)

Edition of 10

Set of 5

(9755)

Chen and Efrat, Herzliya, Israel, May 21, 2005

Archival inkjet print

Image: 10 7/8 x 13 5/8 in. (27.6 x 34.6 cm)

Frame: 21 1/2 x 24 x 1 5/8 in. (54.6 x 61 x 4.1 cm)

Edition of 10

Set of 5

(13139)

In 1999 in Herzliya, Israel, Dijkstra began another six-year project photographing twin sisters Chen and Efrat, memorializing particular moments in their childhood and puberty. Here, the narrative of change mapped through the five double portraits is complicated by internal narratives that can be read in the subtle differences evident between the supposedly identical twins within each image.

"Every time I make a portrait, I see it as an encounter."– Rineke Dijkstra