Exhibition Information | List of Works | Press Releases: English | French | German | Listen on Apple Music | Spotify

Exhibition Dates: 20 January - 13 March 2021

Interview: Christian Boltanski at Galerie Marian Goodman

Christian Boltanski, one year after your show, a major retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, you are presenting a new series of works. Which provided the initial emotional impulse for these new works?

Boltanski: Even if not explicitly so, it has something to do with the lockdown, I think. All of this work was created during the lockdown, roughly in the past year. They reflect a general atmosphere of fear and depression. I didn't want to create something directly related to the situation.

Rather, it's a spirit, an allusion to what's happened or is still happening. The title of the show, "Après (After)," is a term I've used frequently in the past five or six years. It was also used for a show in Italy: "Dopo (After)." It was "Na (After)" in Amsterdam. I quite like the word "after." But "after" refers more to what happens to us after death, not necessarily to what comes after today. Moreover, I chose the title because of the Centre Pompidou show: It means "after" that show.

Three series of works are on display in this show. Are there three compelling words to describe the slant of the individual works in this "Après" show?

Boltanski: Of course, a lot of what I do depicts a path, a development. To come back to something I did at Centre Pompidou: There is a departure and an arrival. In the interior of the gallery, a much smaller space, there is one path. Broadly speaking, there are... ...many works in the various spaces. In the first space we come to, there are at least two works.

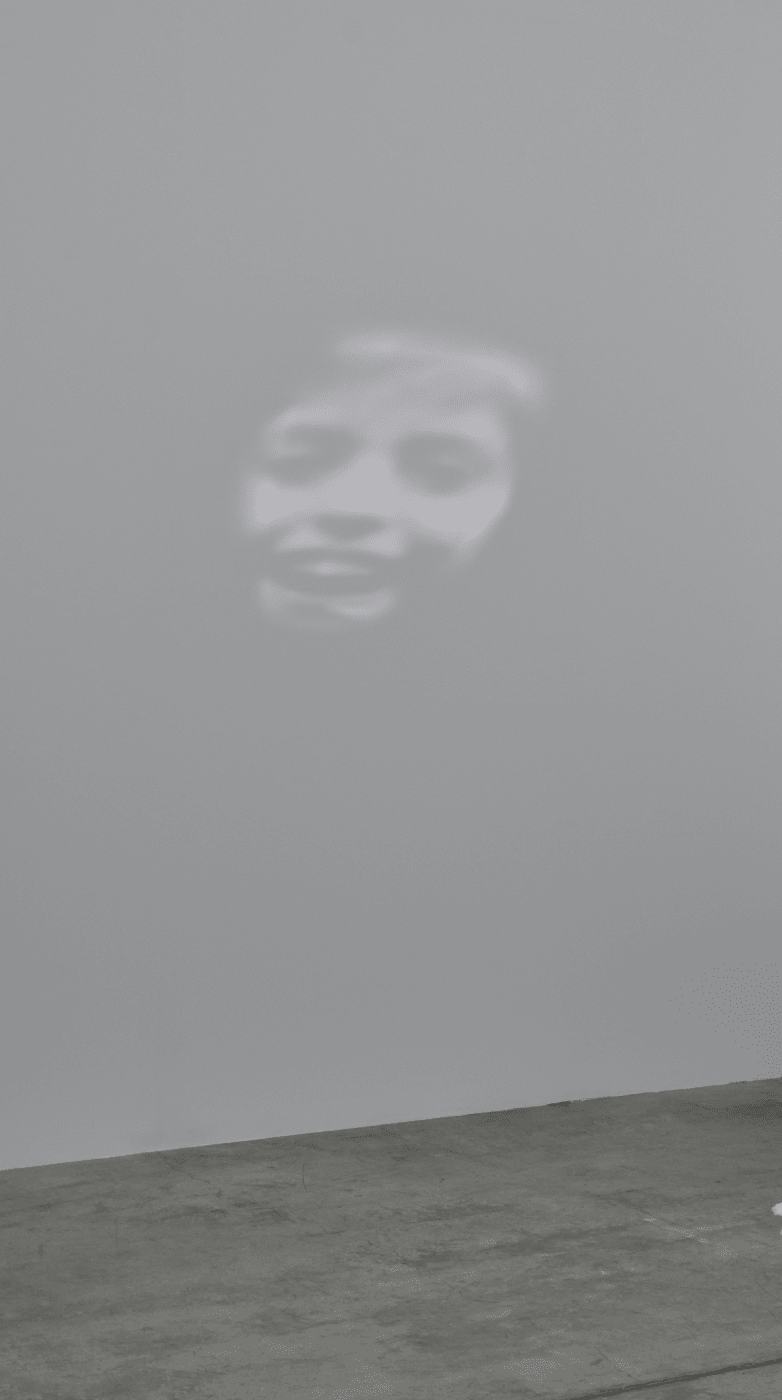

There's a kind of overall vision with stations. It's about "spirits," as there are in every show, but the ones here are our spirits, which are closely connected to us. Which we remember, which appear on the wall to those who want to see them or those who don't want to see them. Then there are these large... masses of white cloths. On the one hand, there's the association with sickness or perhaps something sexual or something left behind, like old sheets in a laundry room.

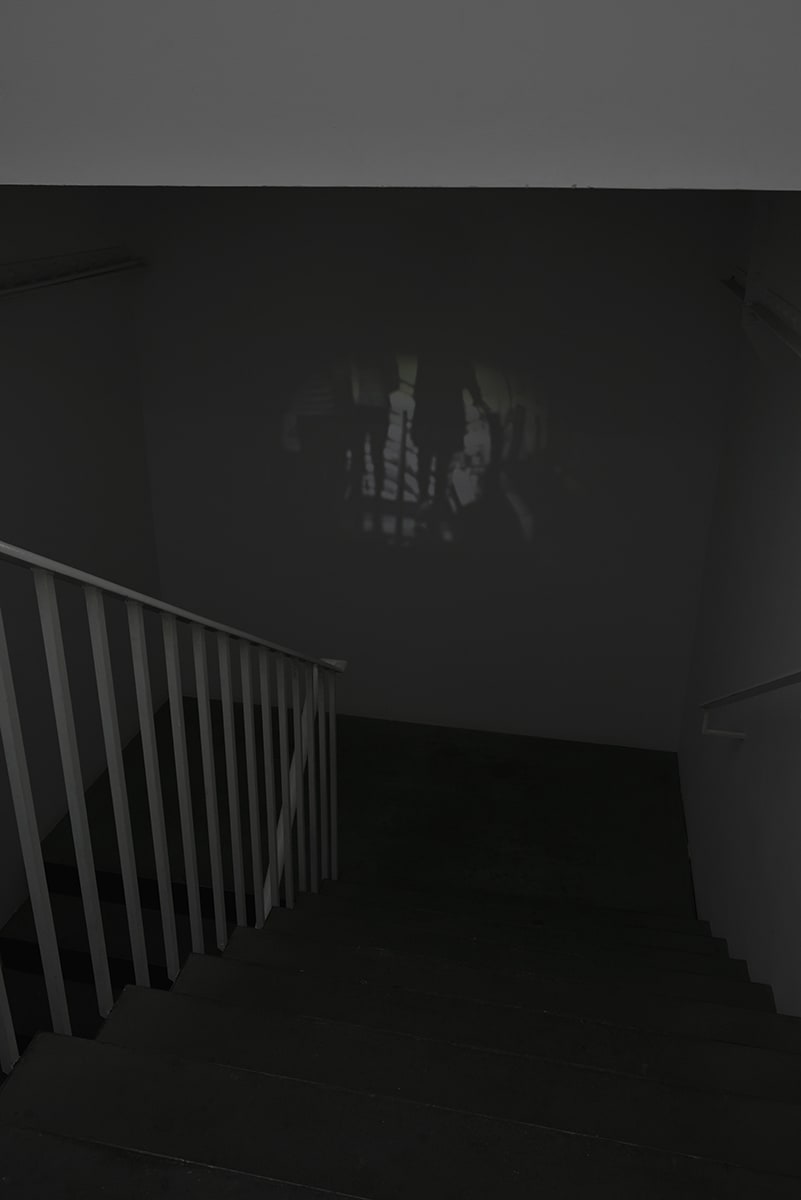

If you go downstairs, there's a short video that was shot at the Centre Pompidou. In it, we see people descending in an elevator... descending an escalator. We see them disappear. They descend into the bowels of the gallery. That's a little tongue-in-cheek, as it were.

Downstairs there are also "spirits." These spirits are more common to my generation. You see four images. These cliché images are in the style of old-fashioned calendars, representing the four seasons. But they have no aesthetic value for me, or perhaps they're too aesthetic. And they contain a barrage of subliminal images from all the massacres in the 20th century. It's the memory of people my age. Several of these images are totally invisible. There are a total of between 150 and 200 images. If you look closely, you'll see a few of them. I can't discount the fact that we live in a world that is closely related to the advertising world.

We live in a cheery, optimistic world. And within all of that there are always horrors and catastrophes. Club Med shows us the beaches on the Mediterranean, but not the migrants who drown in it. Nonetheless, when I see a beach today, I think of everyone who drowned in the sea nearby. And that's why it's a kind of... On the one hand, nothing is happening. It's all perfect. It's all polished. On the other hand, some people like me see the horror in it.

I have a tendency to say that we are at war. I mean, the war isn't over. Somewhere, there's always a war raging and horrifying things are happening. Right now it's not happening before our eyes. But it's not far away. And that's why it's interesting to know that.

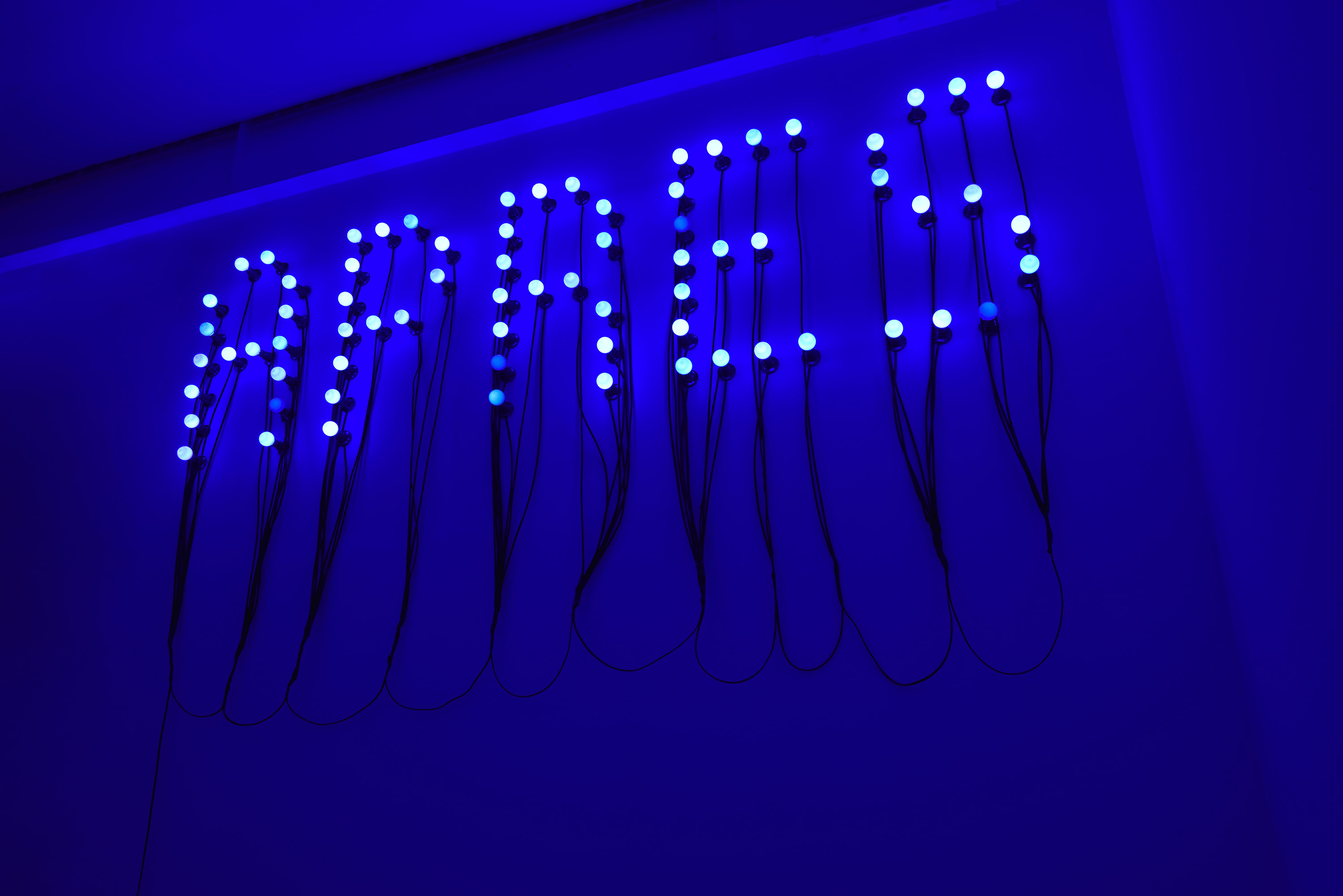

Then you go out and enter a narrow corridor, bathed in blue light, with the word "after." And that's where you really enter the Hereafter. Whether or not it's death: We're in the Hereafter.

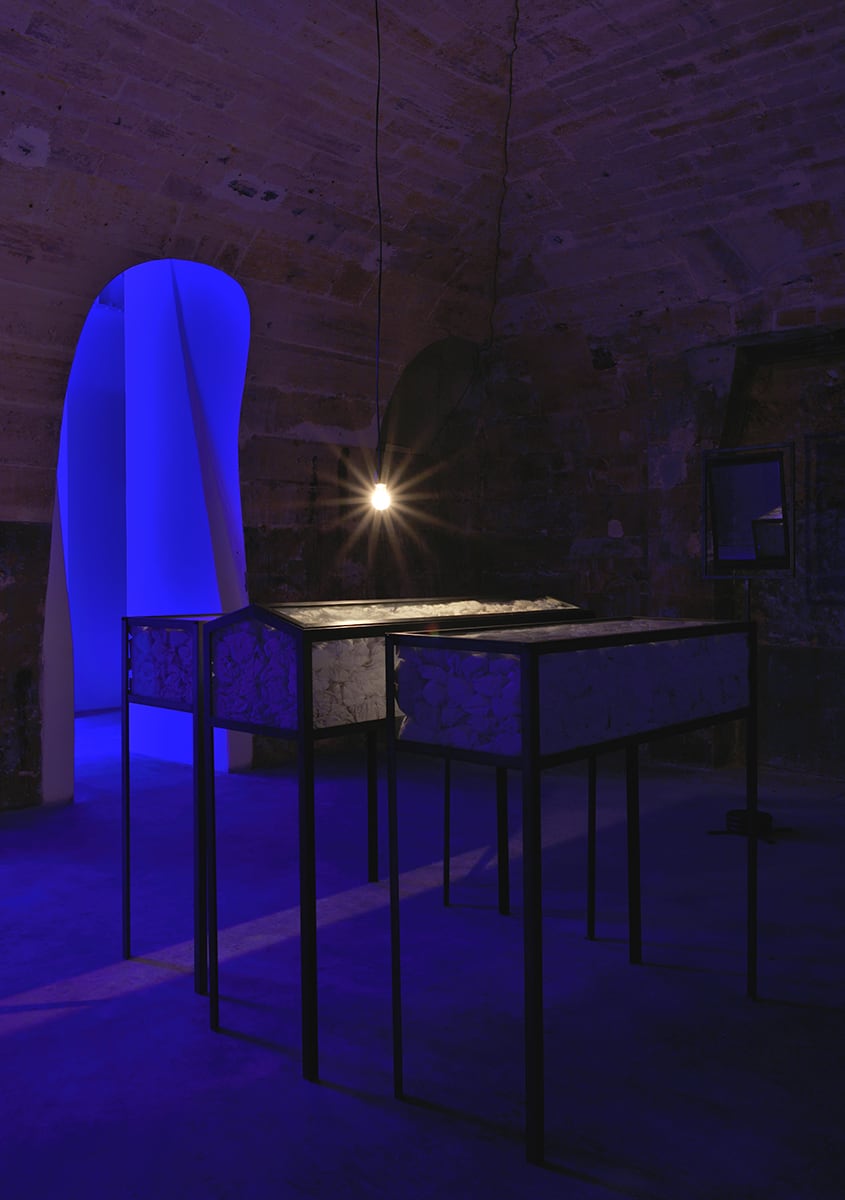

You end up in a crypt with three display cases, which also contain white cloths. But the white cloths here have been placed behind glass, quasi asleep. In addition, there's a one-way mirror. You can... see yourself in it, but you also see the ghost of yourself.

I was told that at Shinto shrines there is a series of initiation rites, passages from one space to another. Only the initiated may enter the final space, which contains a mirror. What do you see, when all is said and done? Yourself. The show is a little like that. But on the whole this show is a place to ask yourself questions, as is often the case in my work. I don't want to explain too much because we all have our own responses to it. If a child thinks that it's all cheerful, I'm delighted by that. I think you get what you need out of it. Everyone reads the work differently. That's the beauty of visual arts: Everyone interprets the work differently.

As previously mentioned, last year you presented "Faire son temps." Today we're discovering "Après." So it keeps going?

Boltanski: There's always a Hereafter until the final Hereafter. But as a matter of fact... I've already had many retrospectives. Especially in the Asian region, in Japan and China. But a show in one's own city has a different significance.

My age adds another layer of significance to it. But, as long as one is alive, things stay in motion. I always hope that the final show of my life will be an extremely cheerful one. But because it would be the last show, I'm not doing it. It would mean that I'd die eight days later.

But one thing's for sure... What we do is related to the general mood. For example, since COVID, there's been the interesting and awful fact that death is no longer being hidden.

Every night the deaths are reported: "Today it was 352. Yesterday it was 323."

This presence of death... I said that we are totally in denial about death today. And we don't accept it. in my youth, you wore a symbol of mourning when you lost someone.

That would be impossible today. You can't even talk about a loved one who has died. It's not polite to do so. And even if you don't die, one day they'll pull the plug on you.

Death-related rituals with family members became a thing of the past. And today, because of this disease, death is being discussed again as something omnipresent surrounding us. That's bound to be of interest to me. I'm not saying that it's good or bad. But it's interesting. It revives an attitude toward death that existed about 70 years ago.

Is this a way to combine things that you used to separate? Like what you've called "minor history" (or personal mythology) and "major history"?

Boltanski: Yes, the work on the lower level of the show certainly deals with "major history." In that sense it's more political than my other work. It's about the horrors in the world. Not to compare myself with him, but it's like Goya and other artists in this tradition who tried to address the horrors in the world. And the upper level of the show is more directly related to me. The phantoms there are my phantoms. The phantoms downstairs are universal. It's a reference to our common history. If you look closely... But it happens so quickly you can barely make out a thing. Someone from my generation would recognize every one of these images. The images are well known. They're practically integrated into our global collective memory.

You might say... I mean, you're always telling the same story. Well, I am. You create the same work every time, more or less. The early lives of all artists are marked by a trauma that they spend their whole lives discussing. But the age of the artist will determine the way that trauma is discussed.

So you might say that this show contains references to the era we live in, but to my age as well. I've been very interested in death for a while now. It's a recurring theme in art, but usually the death of others. But the older you get, the more it's about your own death. So it relates to this initial trauma and at the same time to the moment when the trauma is examined. That's never the exact same thing.

This show isn't... If you could have mounted it 20 years ago, might it have made a different statement?

Boltanski: It would definitely have been different. First you get a sense of something. Something that becomes increasingly important to me: the fact that it's about something all-encompassing, a path. It's less about looking at a painting. I don't want people to stand in front of a work, but rather inside it. We're inside the work. Visitors stand inside the work, not in front of it. It's important to be inside a work of art rather than in front of it.

In your work you also use many intangible elements. At the Monumenta in the Grand Palais, the cold provided you with raw material. You also worked with light as raw material. The atmosphere... There's always a materiality to your work and at the same time a dematerialized, absent quality, a void.

Boltanski: There's an expression that can no longer be uttered: "Gesamtkunstwerk." It's true that in my current work I sometimes include smells or sounds, among other things. Like light. These elements permeate the work.

What I would like for my work... In the South you sometimes find a church door open, so you go inside. You see a man raising his arms. You smell a scent. Sometimes there's music. You sit down and stay there for ten minutes.

I am not religious at all. So that's not an issue. You don't understand what's going on, but it's a place of meditation. After ten minutes, you've had enough. The door's open, the sun's shining outside. And you go somewhere to eat.

I see art shows in a similar way. They exist on the fringes of life, but they allude to life. And you can take a pause in them. I wish big cities would one day have something like little chapels, where you could escape the noise and the hectic pace and linger in front of something for five minutes.

But you're fundamentally opposed to the idea of holy places, making something sacrosanct. You often mention recycling, reprocessing, a kind of circular flow in your work.

Boltanski: My work is not necessarily stable. The work I'm making right now. I'm increasingly interested in what I call "récits" (narratives). Works like Misterios, which I made in Patagonia. Those objects haven't disappeared yet, but they will. I guess no one has ever seen those massive tree trunks. My name will be forgotten, but maybe the indigenous people of this region will tell stories about the madman who once came and spoke to the whales.

And it will be the same in Naoshima, where right now we've reached 150,000 heartbeats. Japanese people who go there don't know my name, but they flock to the site because their grandmother's heart is there or they want to add the heart of a newborn. It's become a site of pilgrimage. That interests me most. I think that narratives and myths might be more important than the works themselves.

The same is true for Tasmania, where I sold my life to David Walsh. Going there is not important. It's like a narrative: "The Man Who Sold His Life." You accept the fact that you are gradually disappearing and leaving behind a trail? Yes, whatever it may be.

Whether it's the construct of a minor mythology or little narratives. My work is almost always destroyed after the shows. But I can reproduce it. Albeit in a slightly modified form.

And when I'm no longer around to play my own music, I hope that others will play it. And that people will see Mr. X's interpretation of a Boltanski work.

"That's not very good. Ms. X's interpretation was better."

It will be possible to constantly revive my work whenever someone plays and reinterprets it. All of this is a far cry from treating the work as a relic.

I'm closer to the Asian tradition. The temples in Japan are both ancient and modern. But there are people who can reconstruct them. They're called "national monuments" because they possess this knowledge. So there are two ways to convey something: by means of an object or by means of knowledge. In my case, it's more likely to be knowledge.