William Kentridge: Finally Memory Yields

William Kentridge

Finally Memory Yields

18 October - 27 November 2021

William Kentridge on "Finally Memory Yields," his exhibition at Galerie Marian Goodman

“‘Every encounter with the world is a mixture of that which the world brings to us and what we project on to it. The tree is never just itself.’ ”

—William Kentridge, ‘Peripheral Thinking’ Lecture

Marian Goodman Gallery Paris is pleased to present an exhibition of new works by William Kentridge which will open on 18 October, running concurrently with FIAC, and continue until 27 November. This solo show at the gallery and bookshop includes a projection of the animated film, Sibyl, 2020, large unique drawings, as well a selection of new etchings and linocuts.

English Press Release | French press release | Checklist

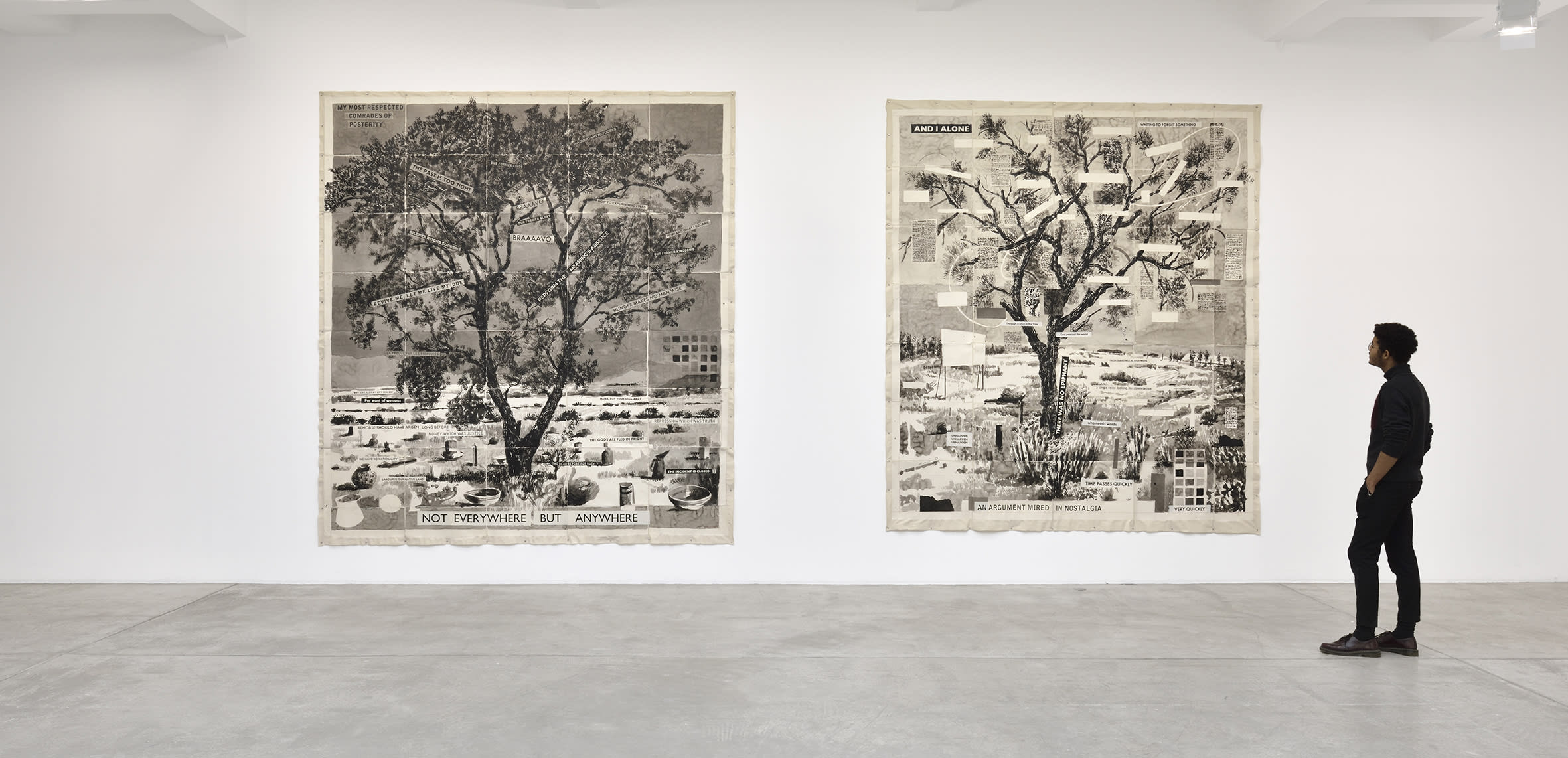

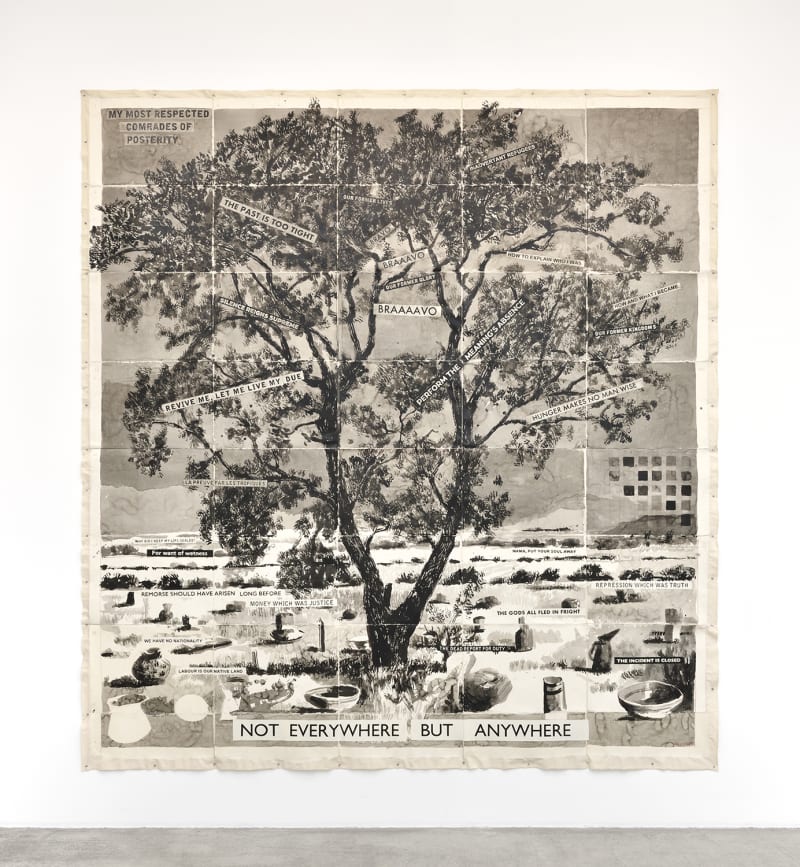

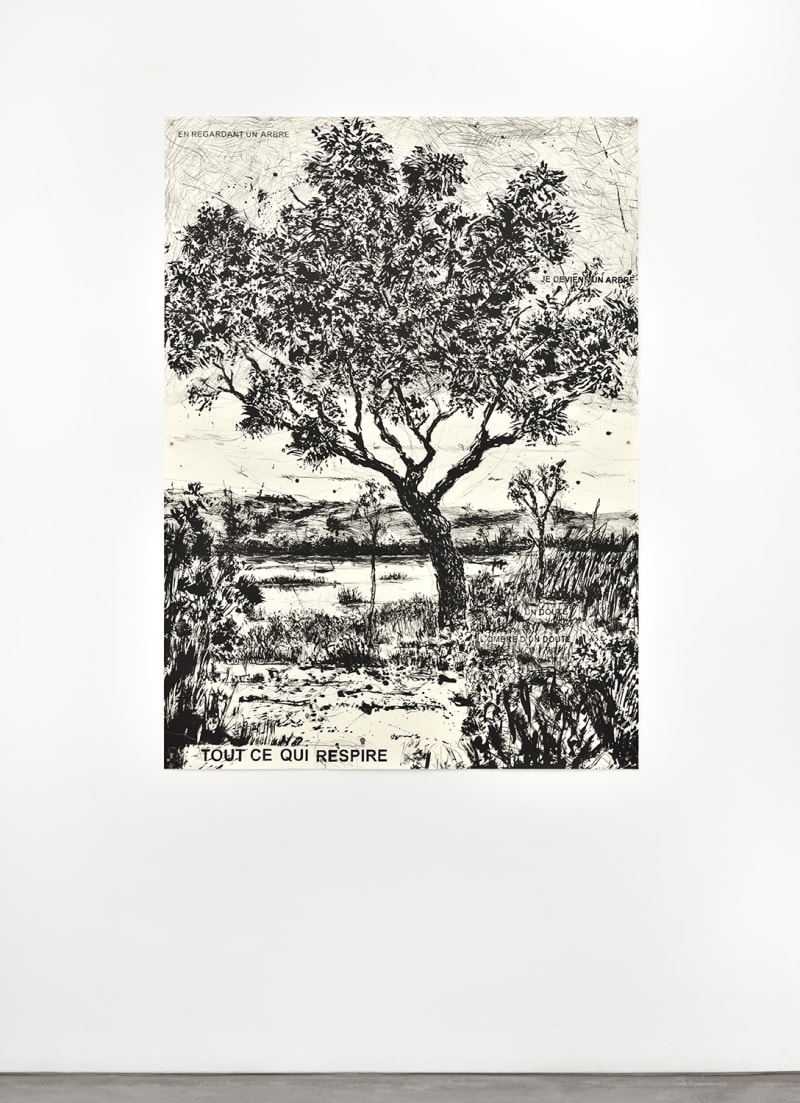

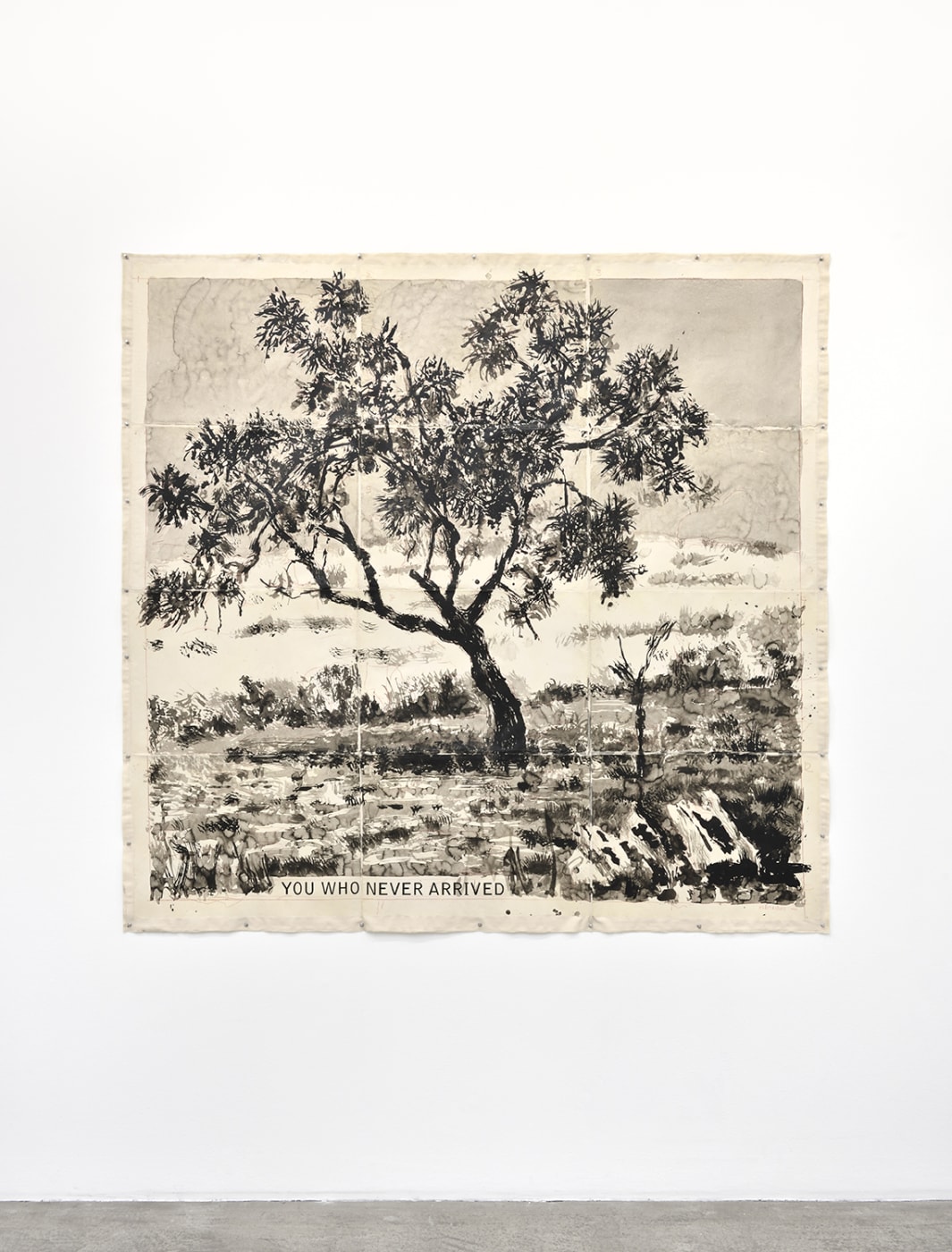

On the ground floor, three new Indian ink drawings of trees will be exhibited for the first time: Finally Memory Yields, Not Everywhere But Anywhere and An Argument Mired in Nostalgia are among the largest trees ever created by Kentridge and will be displayed in his forthcoming Royal Academy solo exhibition.

The trees within his practice were born of two memories and misassociations; a friend describing creating a T-shirt for a companion, heard by William “as a tree search”; and his father representing Nelson Mandela, Albert Luthuli and others in the South African Treason Trial of 1956-1961, which his son misconstrued as “trees and tiles.”

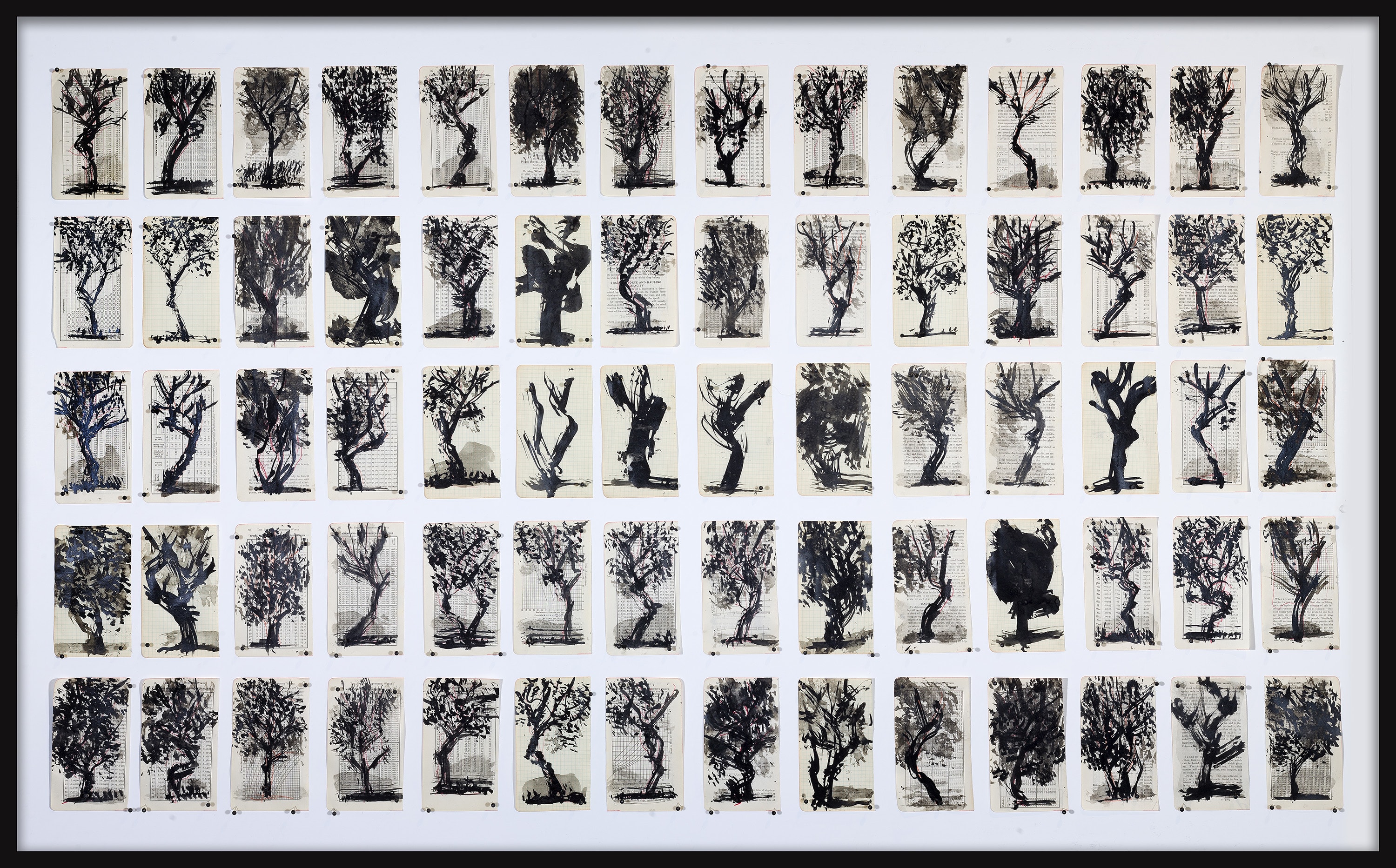

Decades later, whilst working with Indian ink to create images of more precise objects, Kentridge discovered the serendipitous beauty of using a splayed paintbrush to create branches and leaves, wherein the virtue of ‘the bad brush’ is precisely that it “has lost its point, demanding the randomness of foliage.” – Kentridge, ‘Peripheral Thinking’. He goes further in ‘Footnotes for the Panther: Conversations between William Kentridge and Denis Hirson’ – the new French edition of which we will be celebrating with a talk between both authors – that “it was an instance of the materials and process saying: ‘Here are the trees, waiting to be made from the bad brush’.”

Kentridge invariably layers multiple pages of paper to create these works – the ‘tiles’ of his trees – so that, in addition to the intricate foliage of ‘the bad brush’, a dense composite of distractions and associations assimilates and grows with it. The pages themselves are of course the product of actual growth, and Kentridge puts it, "trees led to books, and then on to paper and the words they hold (or release). ”

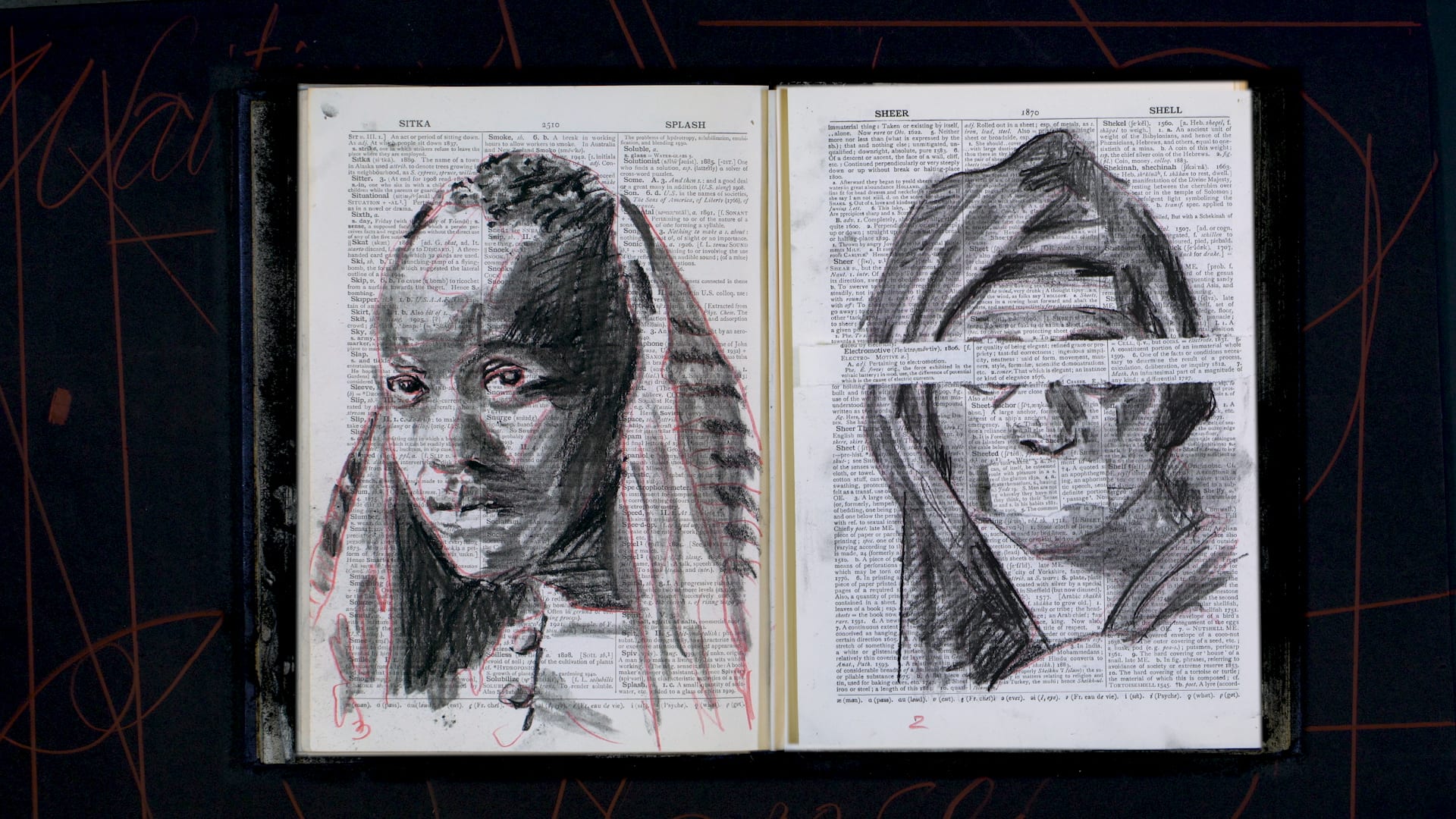

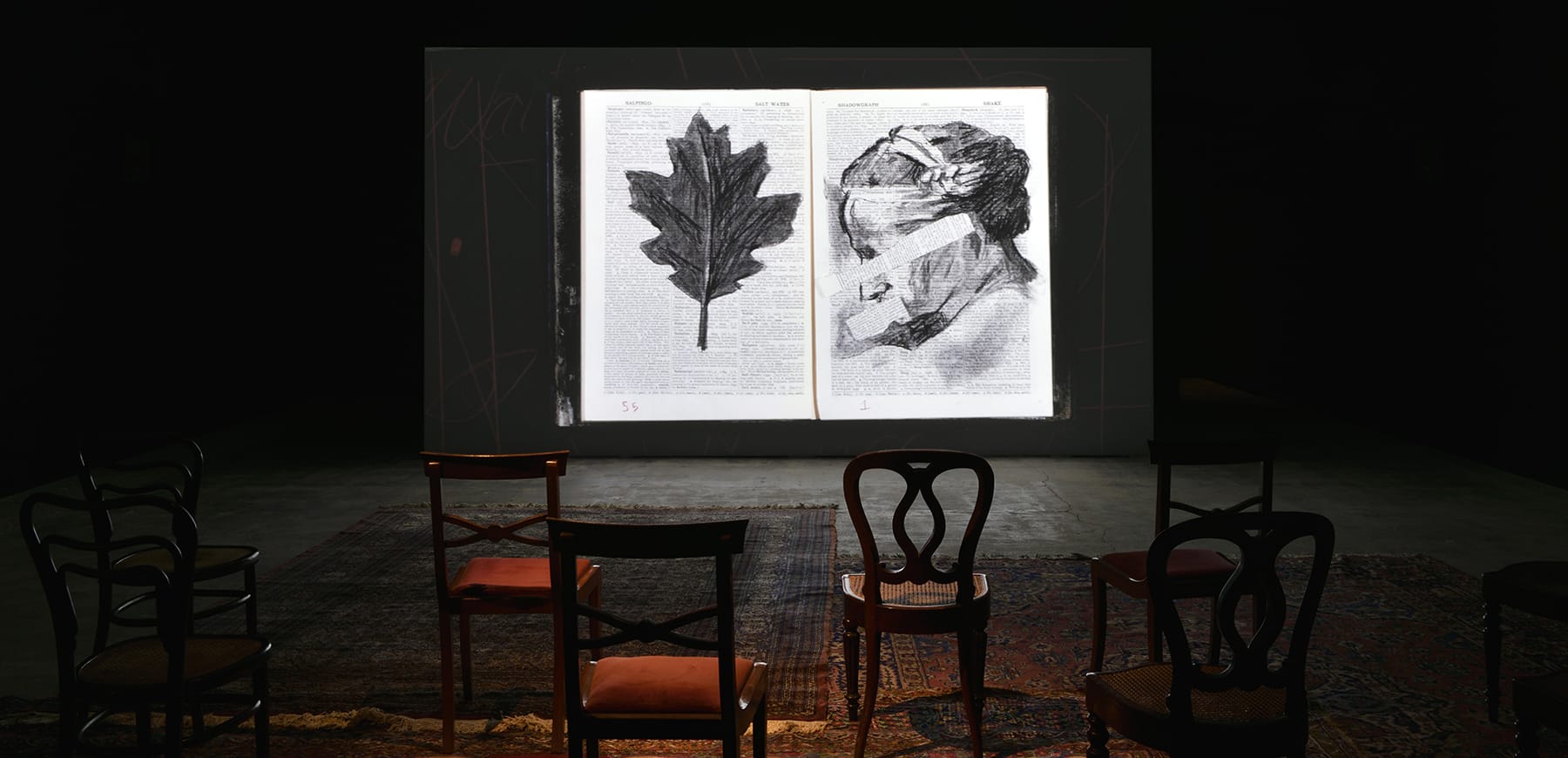

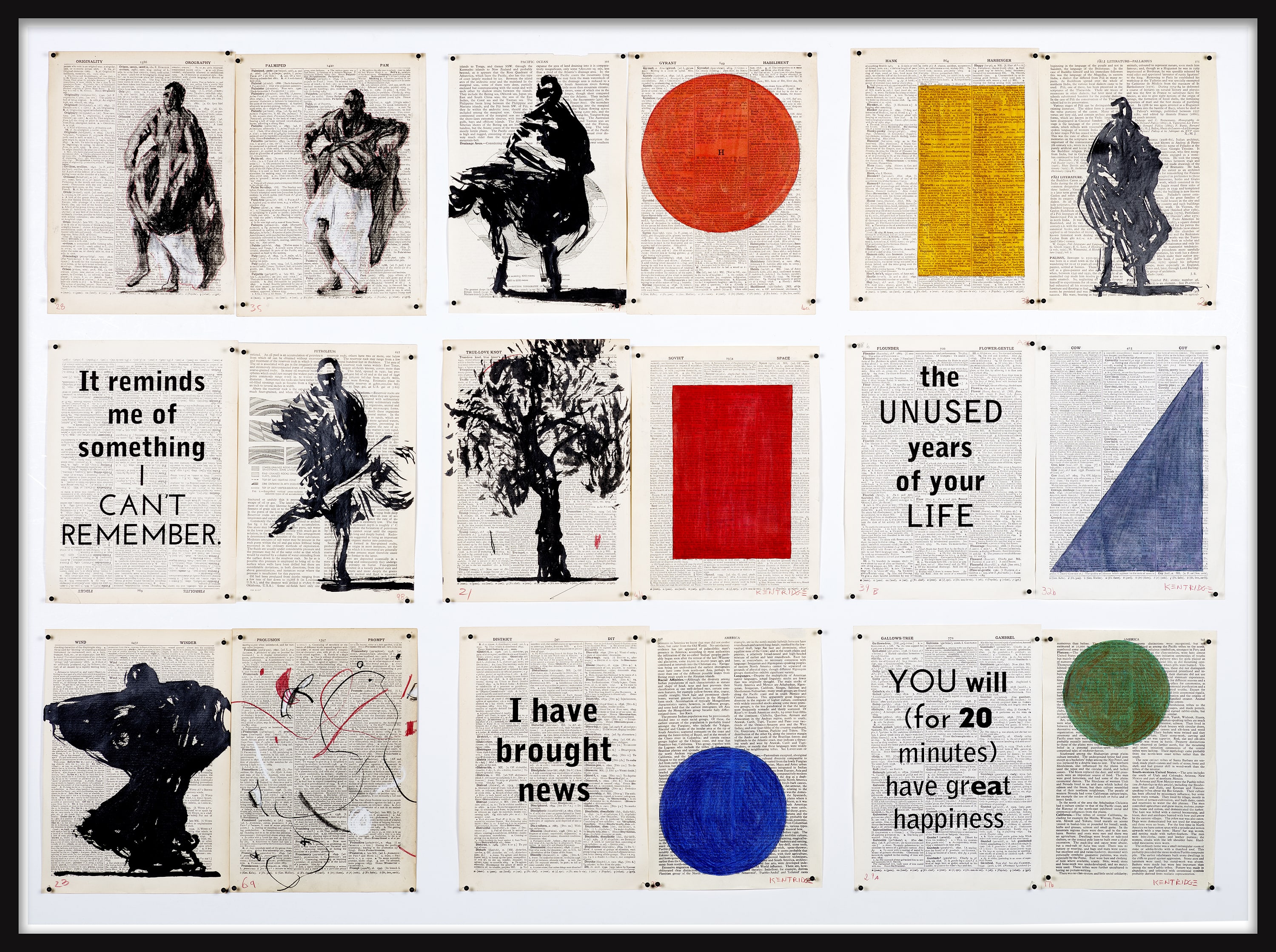

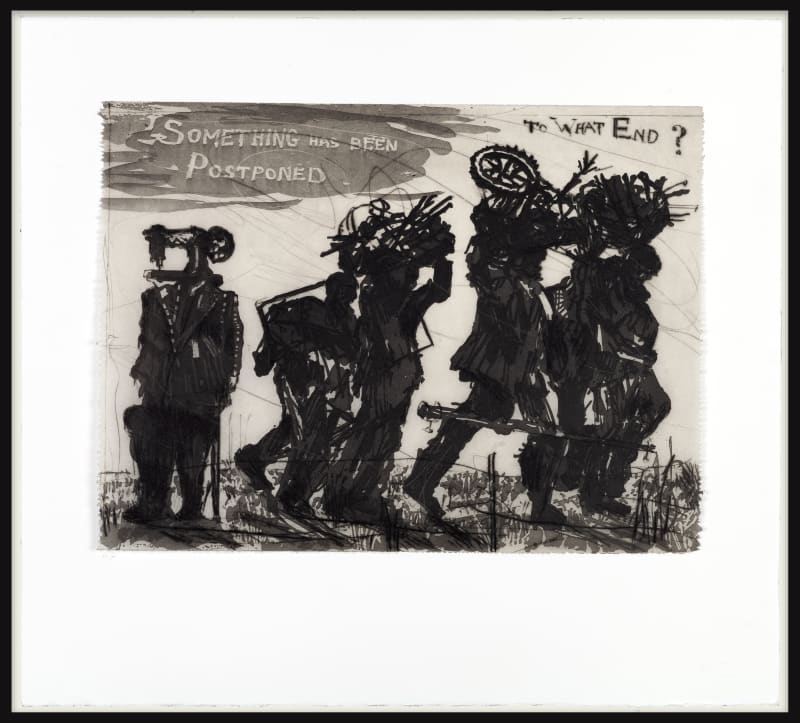

This sense of myriad layers - paper, words and imagery – and specifically a proliferation of oak tree leaves with apparently incidental associations – is evident in Kentridge’s film Sibyl, projected in the lower level of the gallery. Fragments of ruminative phrases flicker on the pages of an unfolding dictionary, punctuated with dancing figures, trees, leaves and geometric forms. Conceived for, and developed from, his chamber opera Waiting for the Sibyl, which was commissioned by the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma and premiered there in 2019, Kentridge collaborated with its composers Nhlanhla Mahlangu and Kyle Shepherd to create a score for the film as cacophonous as the pages he projected. The correlating etchings and linocuts of dancing figures, flowers, trees and leaves that Kentridge has selected and placed throughout this exhibition, all emerge from this trajectory of work and thinking:

‘The Sibyl’s… turning pages allude to the myth of the Cumean Sibyl, who would write your fate on an oak leaf and place the leaf at the mouth of her cave, accumulating a pile of oak leaves. But, as you went to retrieve your particular oak leaf, a wind would turn and swirl the leaves, so that you never knew if you were getting your fate or someone else’s fate. One wishes to avoid one’s fate, but one knows that one is headed directly towards it. You know that it is coming, but you cannot predict it.

Hovering over the piece is the awareness that our contemporary Sibyl is the algorithm, which knows us and our destinies better than we do.

The lines that appear in the chamber opera come from a wide range of sources: from proverbs, from phrases found in notebooks, lines of poets from Finland, Israel, South Africa, North Africa, different places in South America and around the world – which are either used as they were or adapted or changed, but which in some way address the question: ‘To what end?’0

— Kentridge, Johannesburg studio, 2020

Photo credit: Stella Oliver

William Kentridge was born in 1955 in Johannesburg, South Africa, where he lives and works. His work spans a diverse range of artistic media such as performance, drawing, film, printmaking, sculpture and painting. He has also directed a number of acclaimed operas and theatrical productions. Kentridge has participated in numerous significant international biennials, including Documenta X (1997) XI (2002) and XIII (2012) and the Venice Biennale (1993, 1999 and 2005). He is the recipient of numerous prizes and distinctions, including the Praemium Imperiale Award in painting (2019). In September 2021, he was appointed Associate Foreign Member of France's Académie des Beaux Arts.

His most recent solo exhibitions include MUDAM Luxembourg (2021); Musée Métropole d’art moderne in Lille (LaM) (2020); Norval Foundation and Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town, South Africa (2019–2020); and Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland (2019). In 2017, Kentridge founded The Centre for the Less Good Idea, an interdisciplinary incubator space for the arts, based in Maboneng, Johannesburg, with its eighth season taking place in mid-October. From 30 October 2021, Waiting for the Sibyl will be performed live at the Royal Dramatic Theater in Stockholm, Sweden, while his upcoming projects include a substantial retrospective at The Royal Academy in London, from September to December 2022.