William Kentridge: Making Prints: Selected Editions 1998–2021

William Kentridge

Making Prints: Selected Editions 1998–2021

16 March – 17 April 2021

A selection of print works by William Kentridge from over two decades is now on view at Marian Goodman Gallery New York in our Third Floor Gallery.

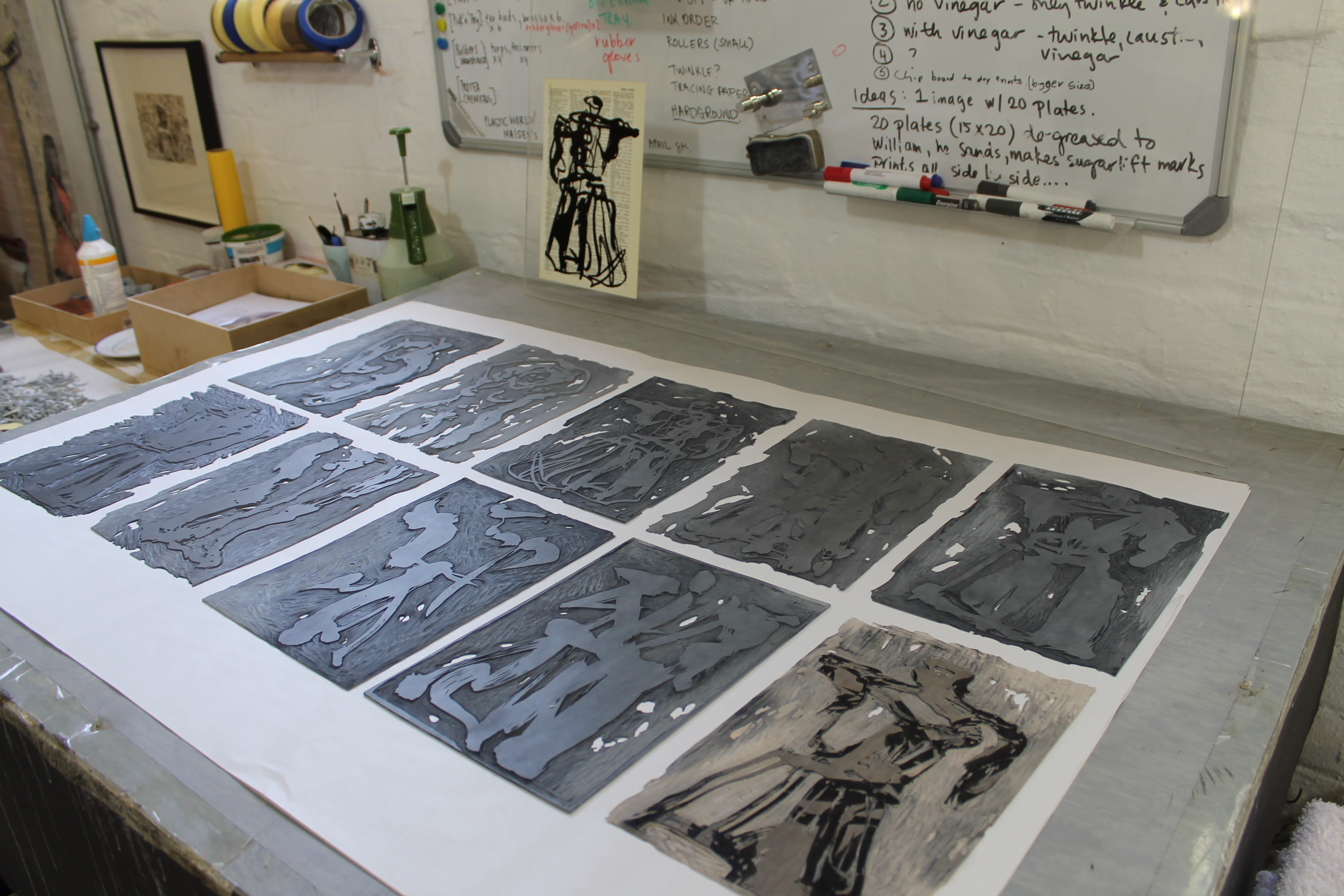

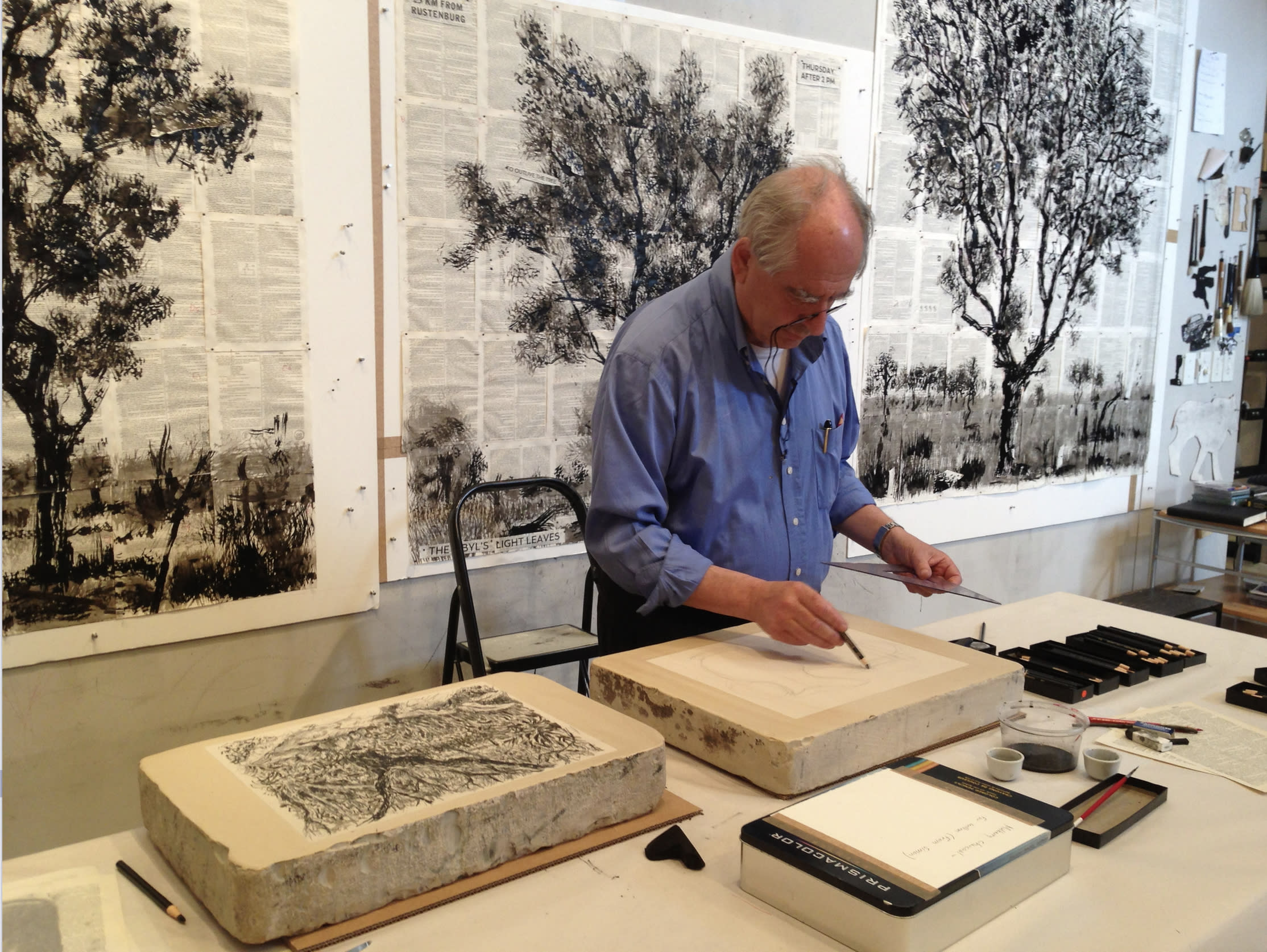

Kentridge’s engagement with printmaking has been integral to his artistic practice and spans his entire career. He has experimented with a broad range of media, from etching to lithography, aquatint, drypoint, photogravure and woodcut, for over four decades. The exhibition’s selection of prints, from 1998 until now, was chosen by Kentridge and includes themes and media that feel particularly enduring and relevant to the artist. In this exhibition, several subjects emerge: sketches that explore a universal archive of ideas; procession, migration and exodus; how history is written; nature and landscape as memory; uses of the absurd, and more.

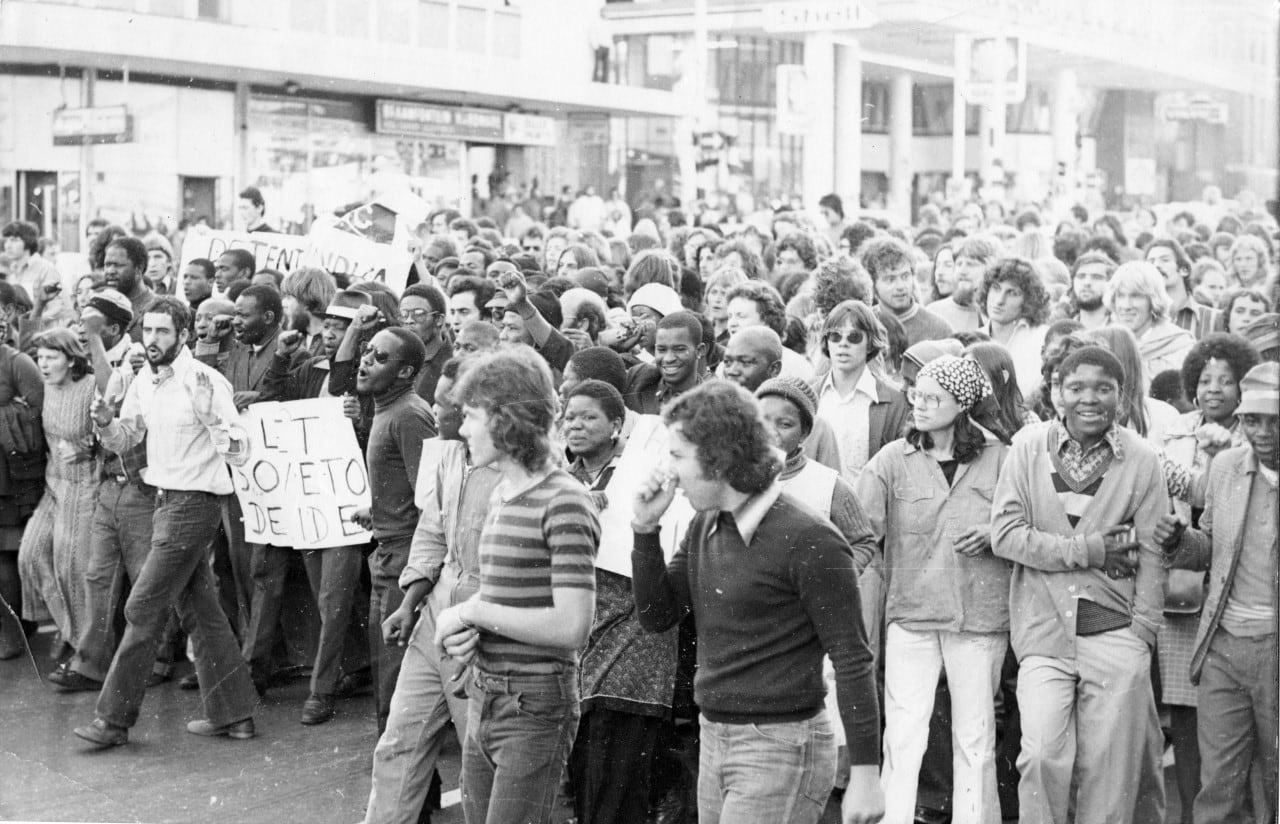

Kentridge began printmaking as a student of art and politics at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg in the early to mid-1970’s, making screen-printed posters for trade unions, student protests and theater companies, which then led to teaching etching at the Johannesburg Art Foundation from 1976-1978. From that time onward, printmaking’s legacy as a democratic art object and vehicle for satire and social change–from Callot to Hogarth to Goya–is as intrinsic to its own history as it is to Kentridge’s. As a South African coming of age under apartheid, he identified a need for expression and experimentation, drawn to the traditions of Beckmann, Dix, Kollwitz, late Dürer and others. Marking or inking, incision and refinement of line, duration and process—the temporal aspect of creating a body of work around layers of a subject—are aspects that allow him to return again and again to printmaking.

Lexicon is the newest group of prints from 2021; they are shown here for the first time. These prints evolved from work by the same title made of sculptural glyphs in bronze. Based on typographic characters that aggregate into ‘paragraphs’ of icons, the five etching and drypoint works included in the exhibition are drawn from a panoply of motifs in Kentridge’s earlier works and notebooks, and are a successor to his procession works. Emergency, Apothecary, Promenade, Forest, Parade summon anthropomorphic bodies activated in time, transmuting from object to figure and vice versa in a state of metamorphosis. Alluding to the aforementioned glyphs which represent the fragmentary nature of thought, they are extracts from an archive of personal images that connect to memory and to the will of ‘what wishes to be drawn.’

Frame: 69 3/4 x 64 3/4 x 2 in. (177.2 x 164.5 x 5.1 cm)

Phrases and fragments of thought in turn can constitute portraits of the self, allowing depiction of an interior life, or of the activity of thinking in the studio. In Hyacinths (Wait Once Again for Better People), 2020, the titular phrase used in the image is from the libretto for Kentridge's recent chamber opera, Sibyl, 2019. In the latter, amythic Cumean sibyl draws men’s fate on oak leaves, only to have them eluded from their grasp by the wind. Hyacinths’ second phrase, God's Opinion is Unknown, is taken from a book of proverbs published in 1916 by Sol Plaatje, South African intellectual, activist, and founding member of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), which became the African National Congress (ANC).

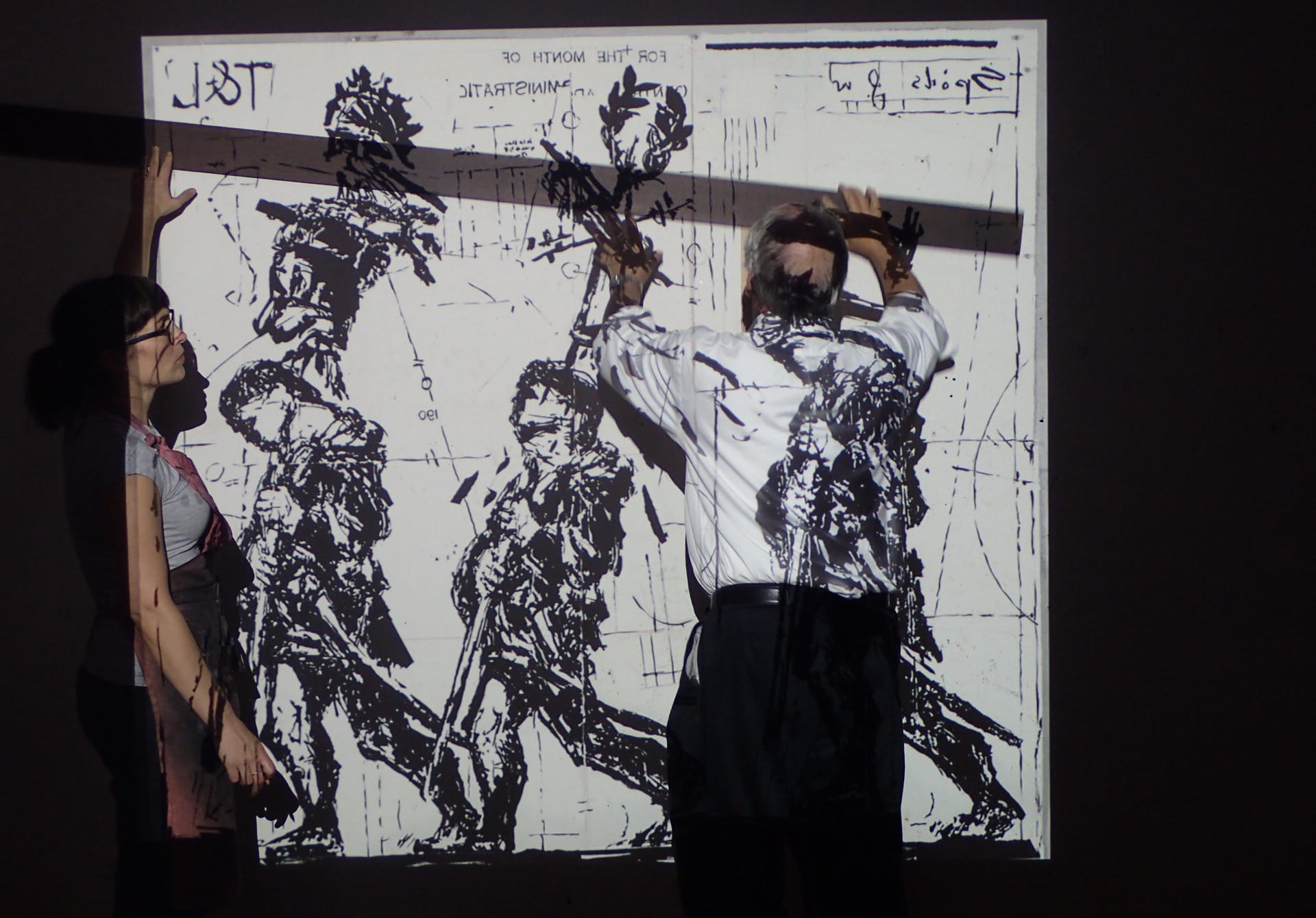

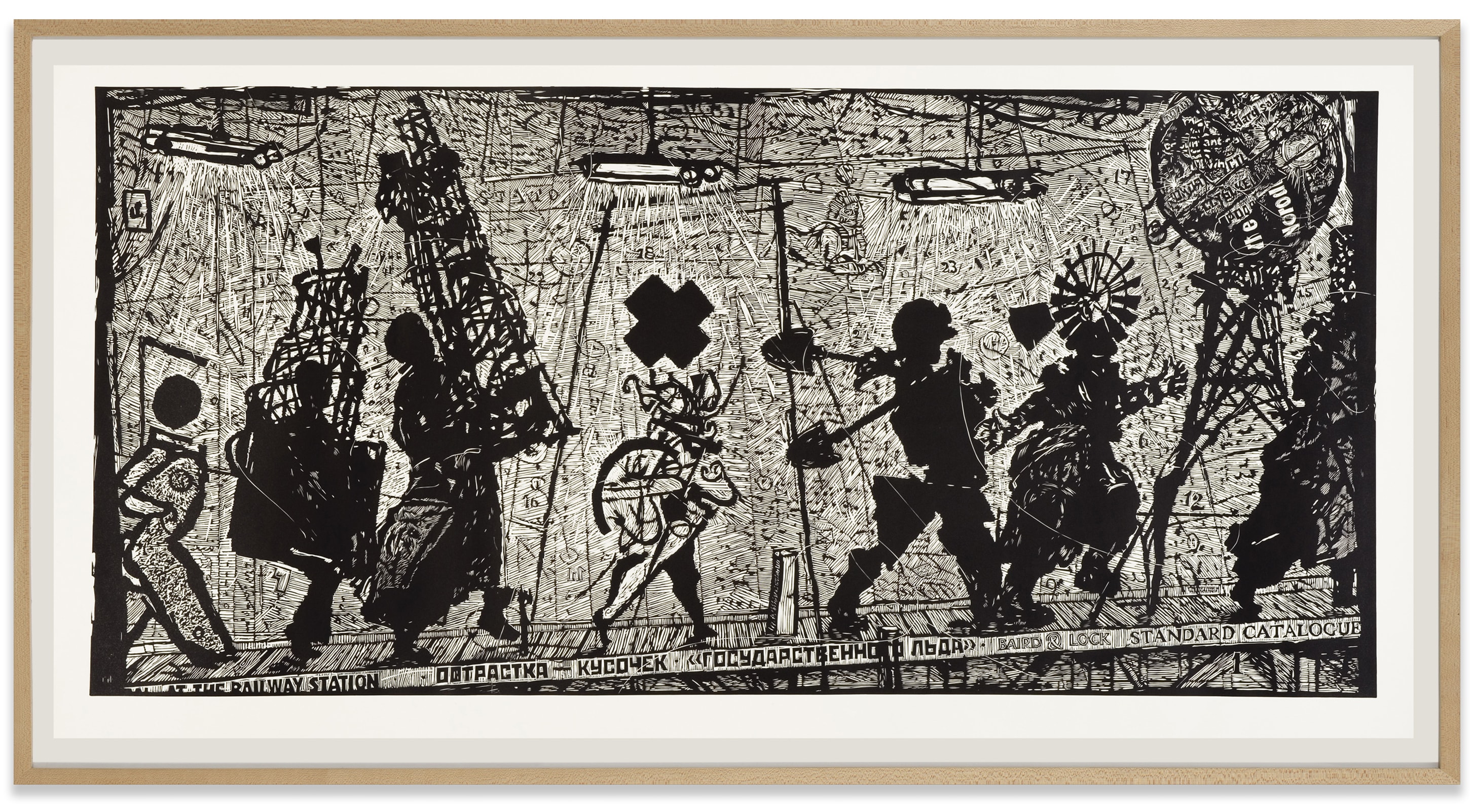

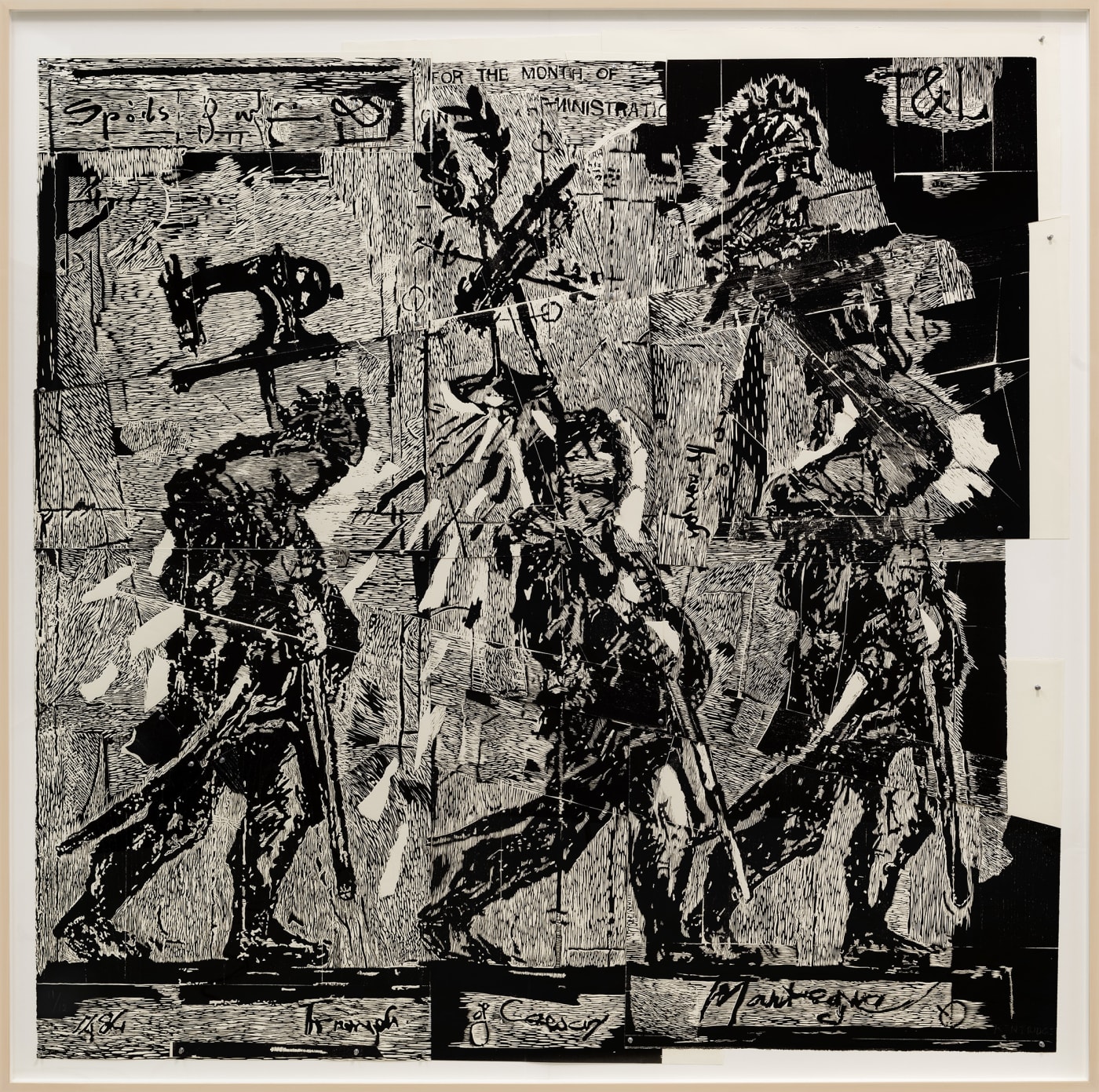

A group of woodcut prints from 2016-2018 relate to Triumphs and Laments, Kentridge’s monumental frieze of images displayed over 500-meters along Rome’s Tiber River (2016). History as a tale of victors and vanquished—and how history is written—are pervasive themes that Kentridge explores. The palimpsest of history—the pageant of ancient and modern characters from Roman lore who will recess into the sediments of time—is inherent to the frieze itself. Invoking the ancient ritual of a Roman triumph underscores what those celebrations omitted: the perspective of the defeated.

Frame: 84 7/8 x 84 x 2 3/4 in. (215.6 x 213.4 x 7 cm)

Kentridge’s Mantegna depicts three figures parading war bounty, based on Andrea Mantegna's Triumphs of Caesar (1484–92) and re-imagined as dispirited foot soldiers bearing hapless objects. The trope of procession is present: individuals carrying the weight of their tragic histories.

Cloth: 66 7/8 x 95 5/8 in. (169.9 x 242.9 cm)

Frame: 70 3/4 x 99 1/4 x 2 in. (179.7 x 252.1 x 5.1 cm)

Refugees (You will find no other seas), 2018, an aquatint etching on paper mounted on cloth, conflatesa Roman naumachia used to simulate battles in the ancient world with a photograph of migrants off the coast of Lampedusa from 2013.

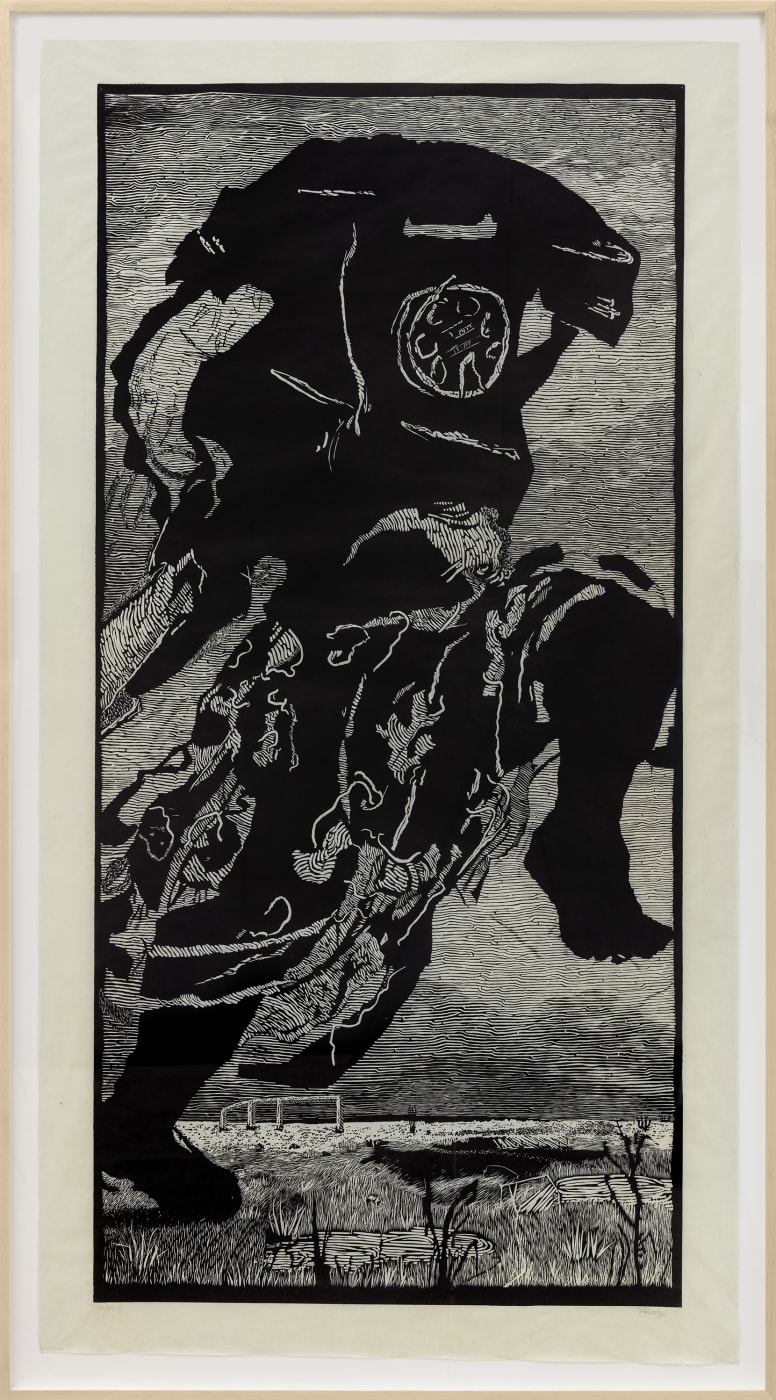

William Kentridge

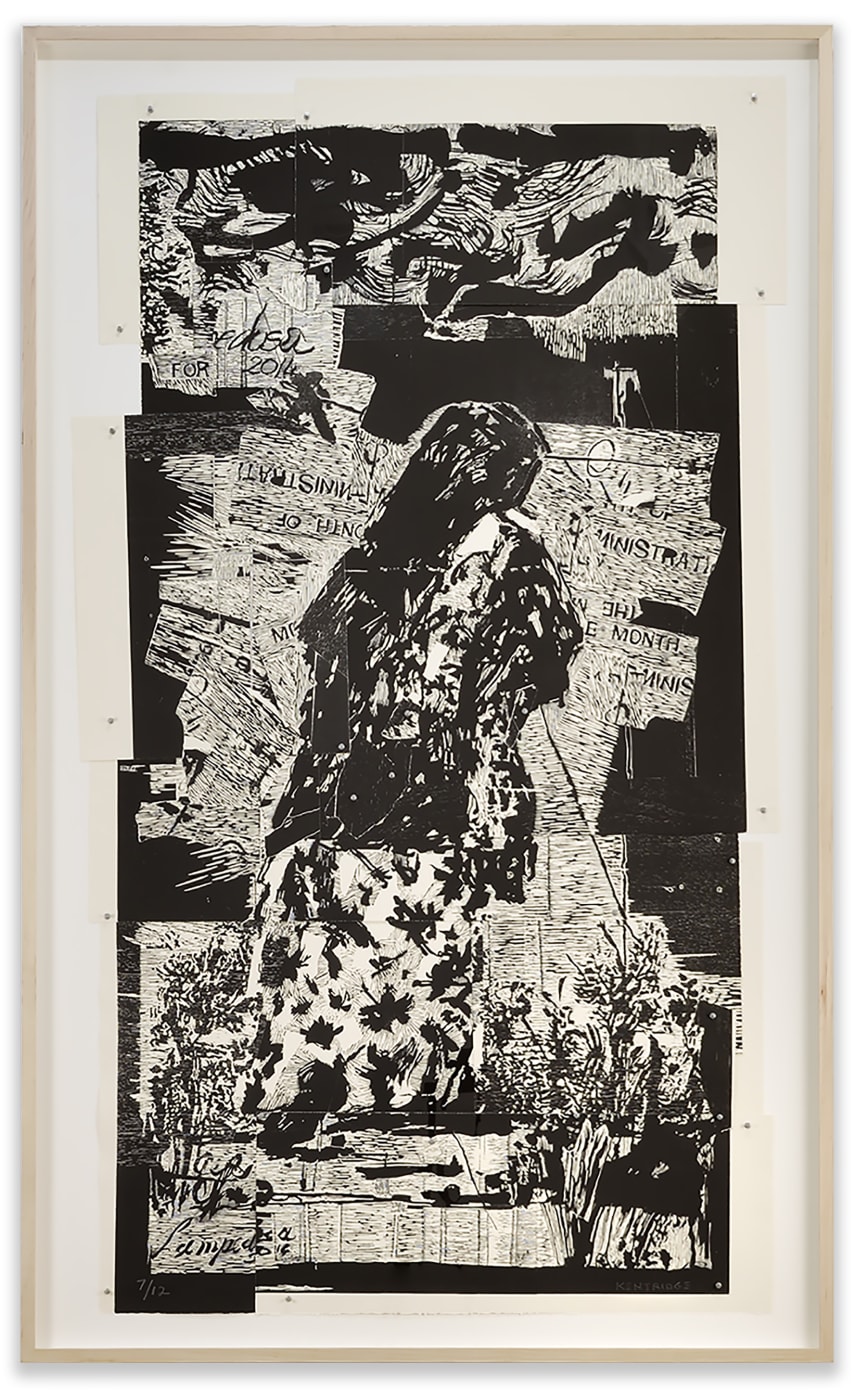

Lampedusa, 2017

Woodcut printed from 13 woodblocks onto 28 sheets of Somerset Soft White, 300 gsm.

81 1/16 x 52 1/2 x 1 15/16 in. (206 x 133.5 x 5 cm)

Edition of 12 plus 4 artist's proof (#7/12)

(19797)

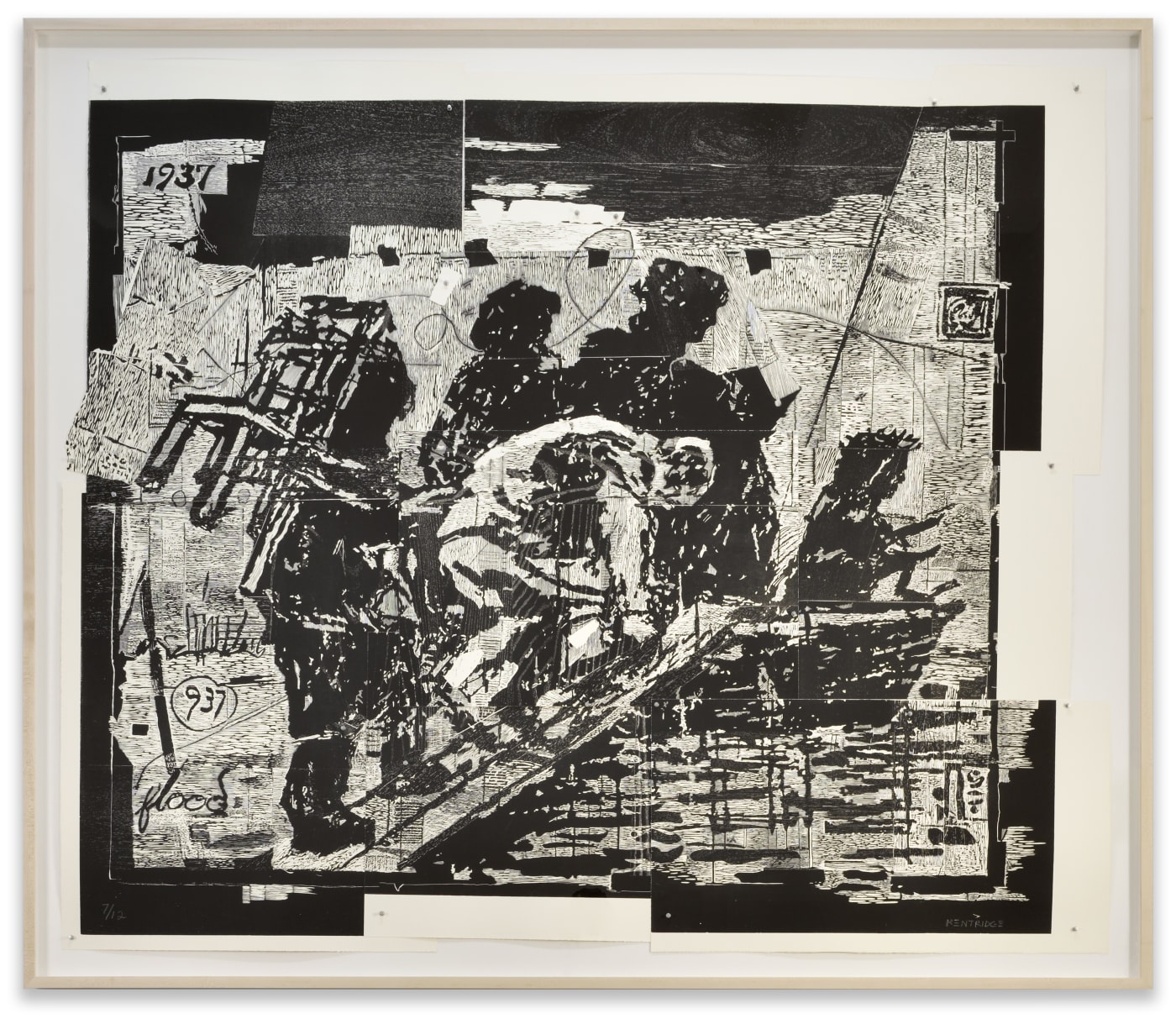

William Kentridge

The Flood, 2016

Woodcut printed from 10 woodblocks onto 15 sheets of various sizes of Somerset Soft White, 300 gsm.

Image: 70 5/6 x 84 1/4 in. (179.5 x 214 cm)

Frame: 77 x 89 5/8 in. (195.5 x 227.5 cm)

Edition of 12 plus 4 artist's proofs (#8/12)

(19786)

A related image of a mourning woman in Lampedusa, a 2018 woodcut, is taken from a memorial service after that same shipwreck, while The Flood, a 2016 woodcut, recalls the flood of the Tiber in 1937.

Sheet: 73 x 40 1/4 in. (185.4 x 102.2 cm)

Frame: 76 7/8 x 44 x 1 15/16 in. (195.2 x 111.7 x 4.9 cm)

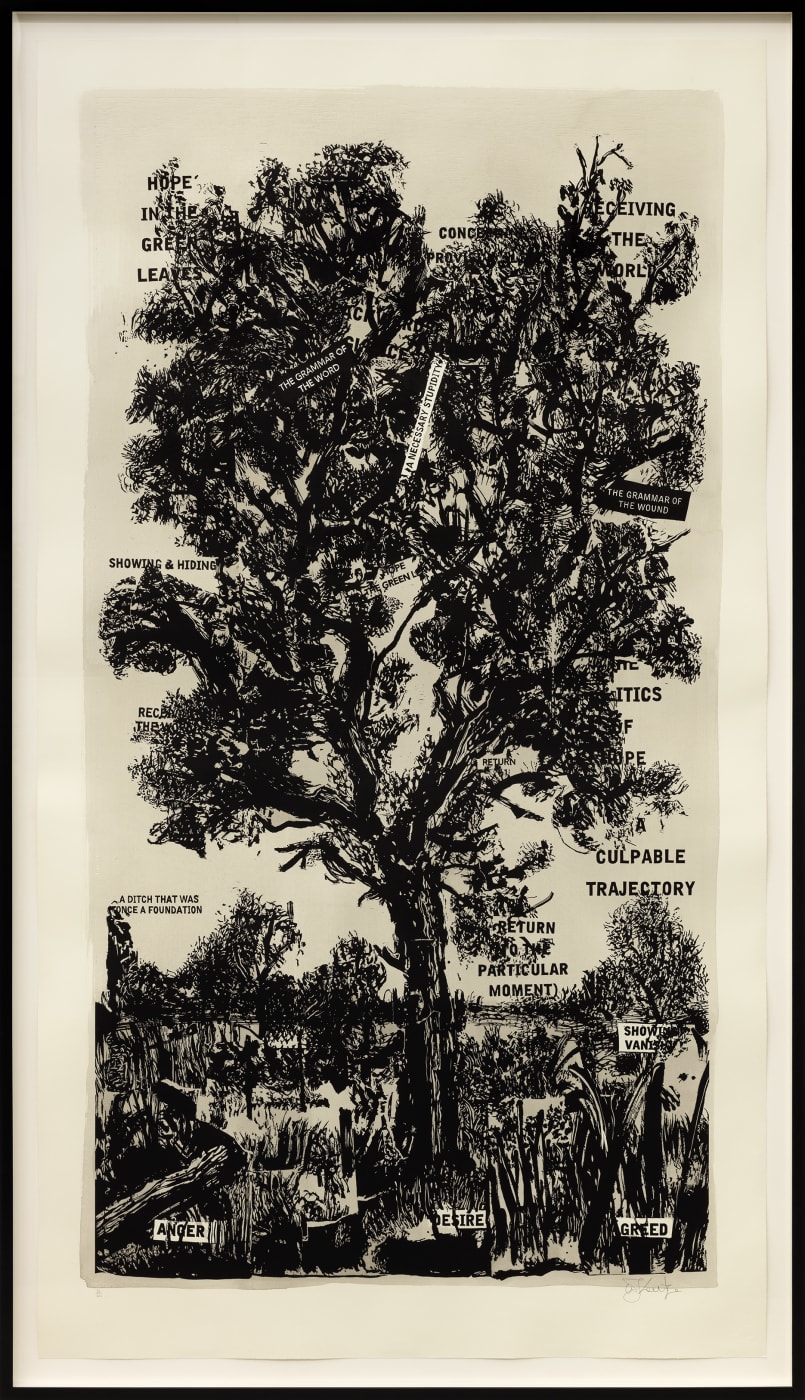

History transferred to memory, memory as the basis for writing, writing constituted by phrases, becoming portraits of the self. Landscape as memory, memory and nature effacing history, and also bearing witness. This cycle is alluded to in Kentridge’s landscape works. A landscape can suggest geological time, the cultural memory of how mining shapes a land or a zeitgeist, or it might bury an apartheid past. Similarly Kentridge’s tree works, whether the tree of life or the tree of knowledge, are witnesses to history. A linocut of trees departs from inky brushstrokes to fine point media on encyclopedia pages in Hope in the Green Leaves, 2013.

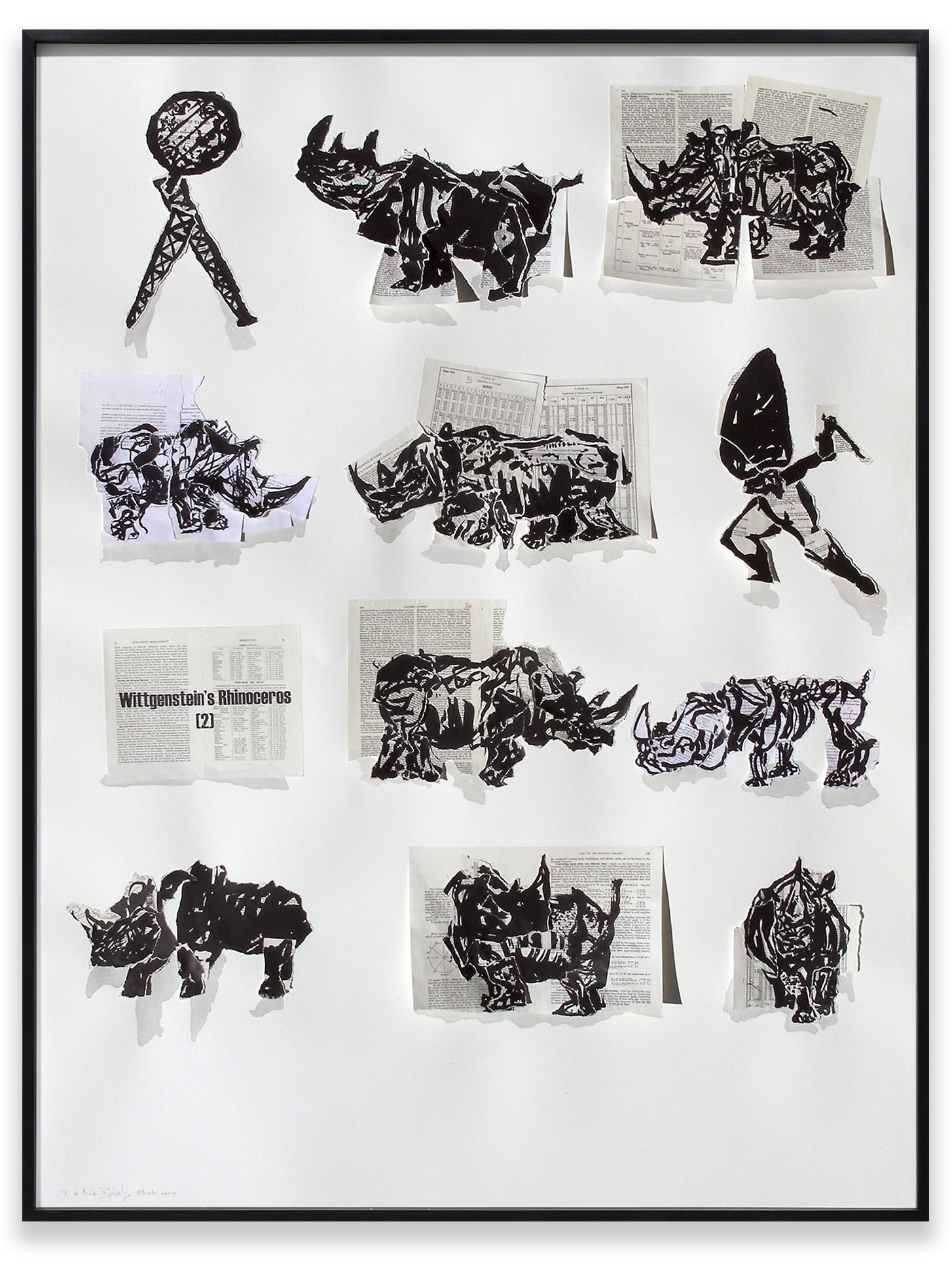

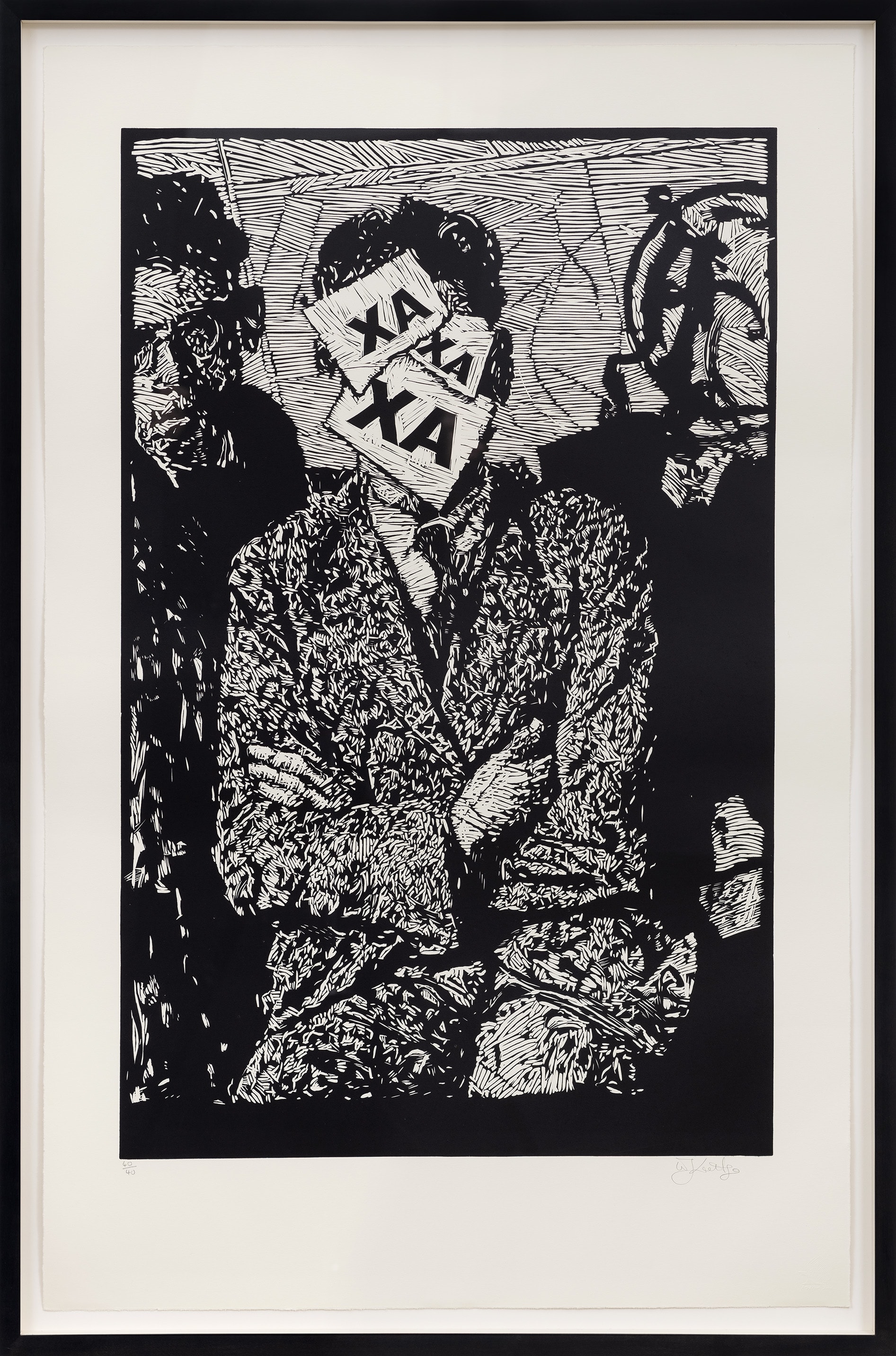

The set of 30 etchings for Nose, 2006-2009, and Wittgenstein’s Rhinoceros, 2007, and later XA XA XA, Portable Monuments and Eight Figures, 2010, were all made leading up to, or concurrent with, Kentridge’s direction of Shostakovich’s The Nose at New York’s Metropolitan Opera in 2010. Using a mixture of three techniques (sugar lift, drypoint, engraving), etchings for The Nose were created originally as a sketchbook of ideas offering different thoughts. In advance of preparations for the opera, Kentridge conducted research to conceive of a visual language for the production, rooting himself in Suprematism and Constructivism in order to craft a formal vocabulary for its staging. Exploring the art and ideology of Soviet history and the despotism of Stalin’s regime allowed parallels to be drawn to the complex situation of South Africa. The aesthetic platform chosen became a way to merge ideas, integrating Gogol’s short story (1830s) on which the opera is based, with research into Russian iconography of the 1920s, the time when Shostakovich wrote the opera.

Kentridge imagines ‘the incomprehensibility of the world through the aesthetics of the absurd—the extraordinary nonsense hierarchy of apartheid in South Africa made one understand the absurd not as a peripheral mistake at the edge of a society but as a central point of construction, so the absurd always, for me is a species of realism rather than a species of joke or fun. That’s why one can take the joke of 'The Nose' very seriously.’

Frame: 92 3/4 x 51 7/8 x 2 in. (235.6 x 131.8 x 5.1 cm)

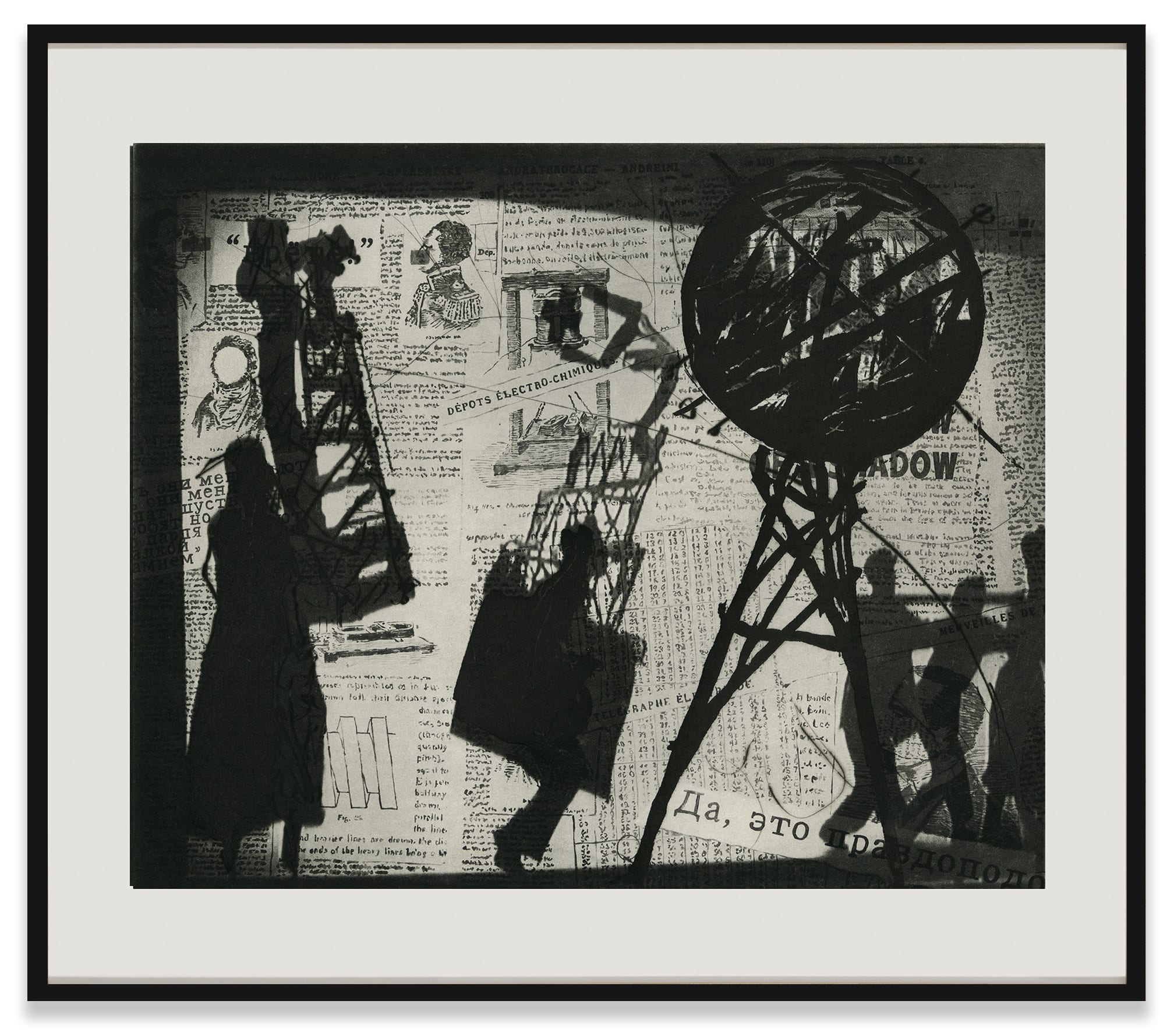

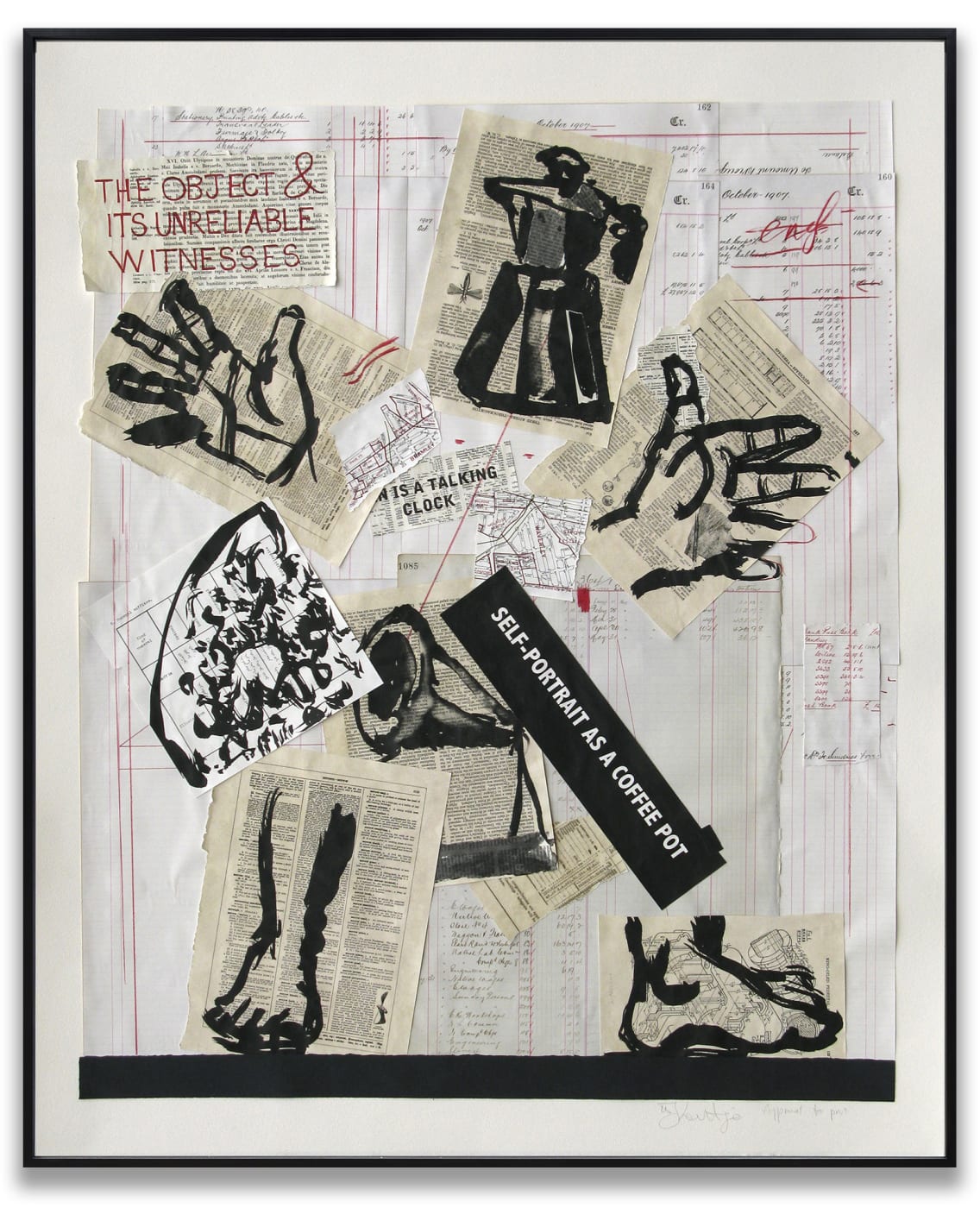

Telephone Lady, 2000, is an example of Kentridge’s experimentation with scale and relates to metamorphosis and the early procession works. The work, a monumental linocut on mulberry paper, was made the same year as Kentridge’s Portage prints and his film Shadow Procession – which were both developed from silhouettes and figures constructed out of hand-torn pieces of black paper.

Frame: 43 3/4 x 36 1/2 x 2 in. (111.1 x 92.7 x 5.1 cm)

William Kentridge was born in 1955 in Johannesburg, South Africa where he lives and works. His work spans a diverse range of artistic media such as performance, drawing, film, printmaking, sculpture and painting. Kentridge has also directed a number of acclaimed operas and theatrical productions.

The first of a five-volume catalogue raisonne of William Kentridge’s prints and posters has been collated and edited by Warren Siebrits in close collaboration with the artist. Volume one, focusing on graphics produced between 1974 and 1990, will be released in early 2022. In addition, Siebrits’ William Kentridge: Domestic Scenes will be published by Steidl, Germany in the Fall of 2021.