Overview

Following an inaugural exhibition of Allan Sekula at the London gallery this spring, Marian Goodman Gallery New York is pleased to announce an upcoming summer show of work by Allan Sekula (1951-2013), which constitutes the largest presentation on the East Coast of this artist and critic’s photography. Sekula may be best known for his substantial essays of images and texts exploring the maritime world, such as Fish Story featured in Okwui Enwezor’s Documenta XI (2002), and subsequent films The Lottery of the Sea (2006) and The Forgotten Space (2010), the latter co-directed with Noël Burch.

Allan Sekula: Labor’s Persistence

June 27 – August 23, 2019

Opening Reception: Thursday, June 27, 5-7 pm

“Beware: A Worker’s Defeat Has Been Converted Into An Artwork” - Allan Sekula, This Ain’t China (1974)

Following an inaugural exhibition of Allan Sekula at the London gallery this spring, Marian Goodman Gallery New York is pleased to announce an upcoming summer show of work by Allan Sekula (1951-2013), which constitutes the largest presentation on the East Coast of this artist and critic’s photography. Sekula may be best known for his substantial essays of images and texts exploring the maritime world, such as Fish Story featured in Okwui Enwezor’s Documenta XI (2002), and subsequent films The Lottery of the Sea (2006) and The Forgotten Space (2010), the latter co-directed with Noël Burch.

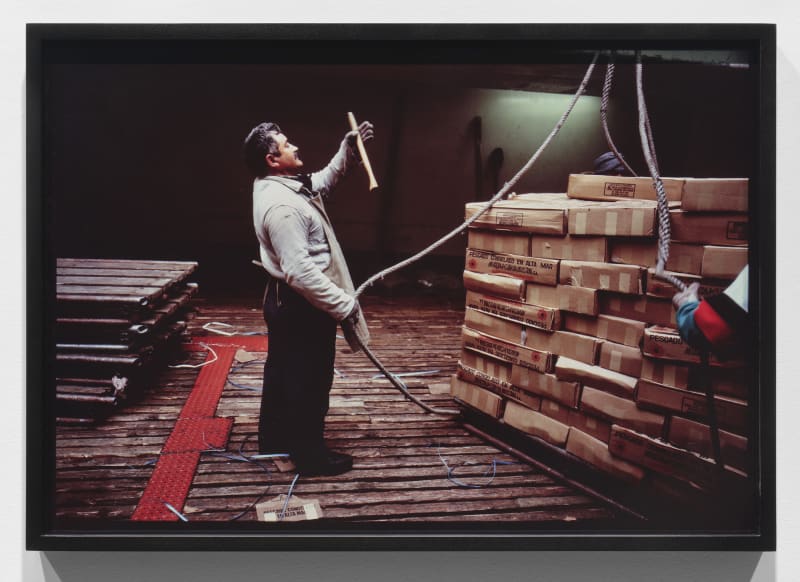

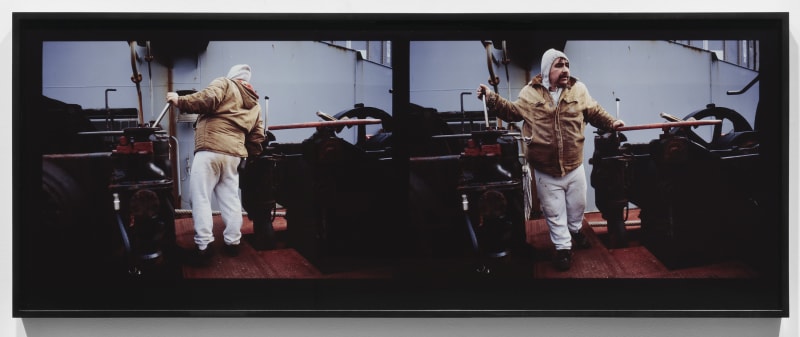

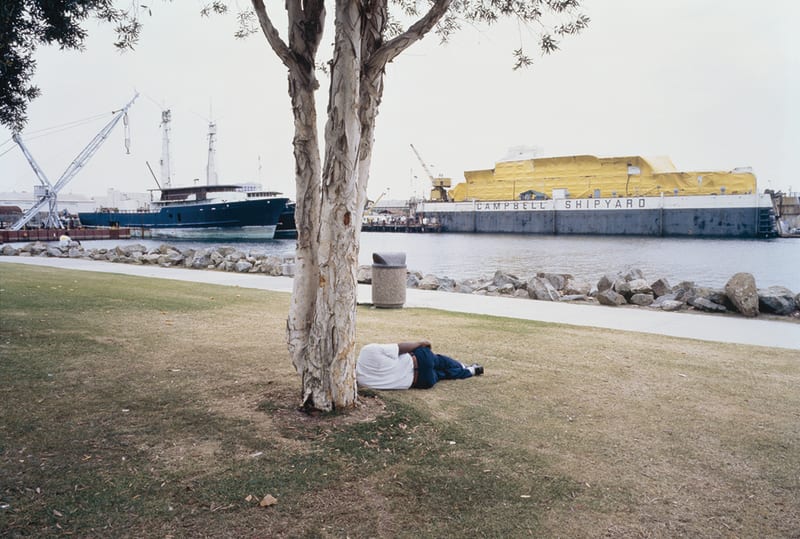

Growing up in San Pedro, the immense port of Los Angeles, Sekula gravitated to the sea as a space of freedom and hard, sweaty work. As important, the contemporary maritime world was a site of rapid changes in modern technologies from traditional bulk holds to enormous container ships and accompanying cranes, which reduced much labor on the seas and in the ports while also greatly increasing global trade and outsourcing of manufacturing to sites of cheaper labor. Thus Sekula, grandson of a Pennsylvania railroad blacksmith, found himself wanting to redirect attention to this largely ignored field of work and commerce in the age of more glamorous air travel and high-speed global communication networks.

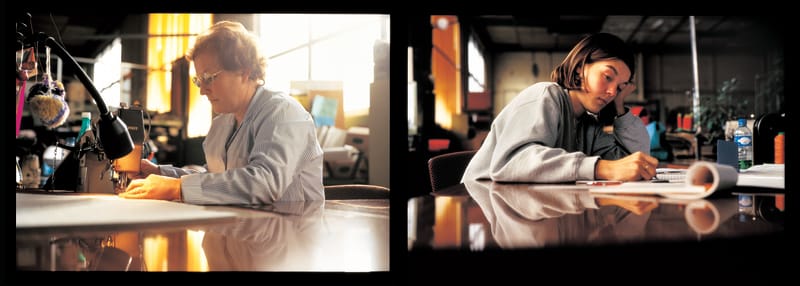

But more than the sea, Sekula’s abiding focus was the increasingly downgraded world of industrial work. An unashamed marxist, he consistently invoked the centrality of the labor theory of value. And following both Karl Marx and Roland Barthes, he protested the commodity-oriented culture’s glossing of the diverse forms of work that make our material world possible. A passing critical comment by Barthes on The Family of Man’s “eternal esthetics of laborious gestures” provoked Sekula’s own essay on the topic of photography’s unacknowledged debt to human labor; even more it inspired his personal quest to feature workers and work in their rarely stable, contingent relation to management, technology, history and regional culture. Photography for Sekula was haunted by both human labor and the hegemonic disregard for such agency and transaction from below.

Even as a student plotting the possibility of living as an artist and activist (at a time when his father had lost his job like so many aerospace engineers during a period of industrial contraction with the winding down of US military intervention in Southeast Asia), Sekula, the eldest of five children, confronted his own precarious social position coming from a family struggling to retain middle-class respectability. As an engaged anti-war activist, he simultaneously sought to figure out how art and photography both contributed to the reigning social order and, if used deftly, might undermine it. Throughout his career, he represented himself as well as others in his depictions of class struggle ever in flux.

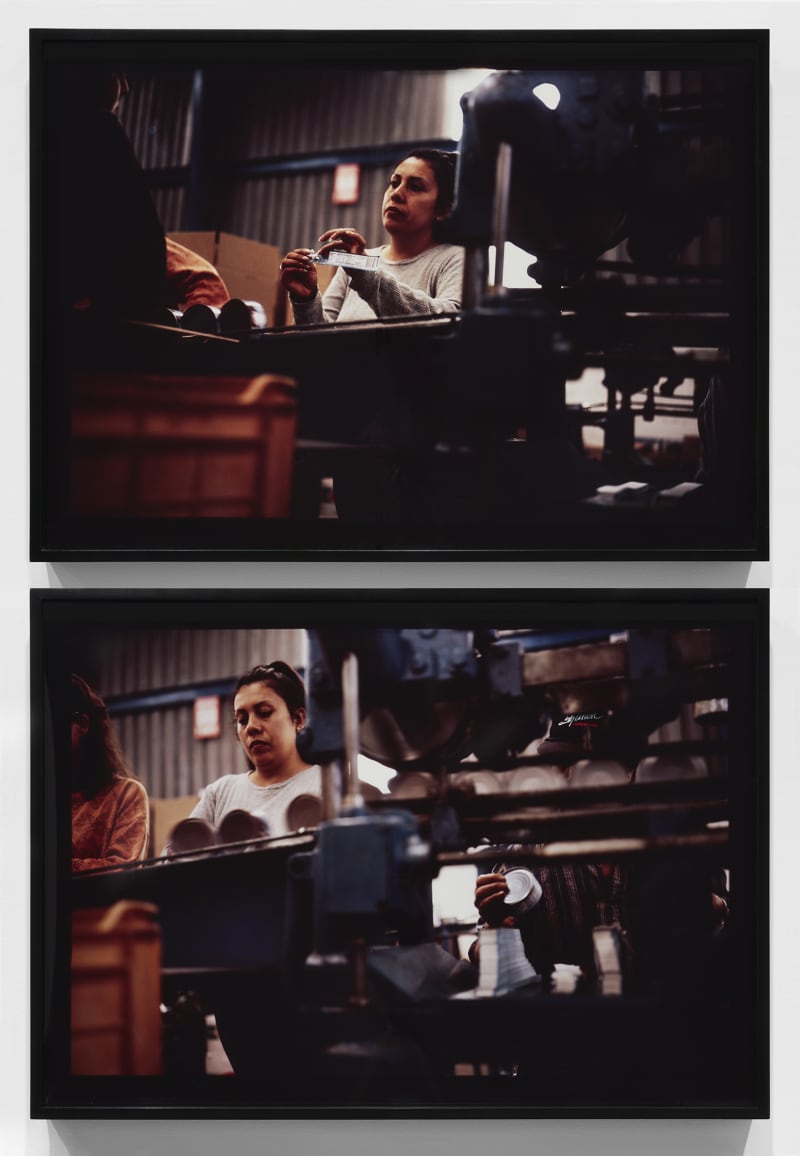

The current survey of Sekula’s works on the theme of labor includes a key selection of five major pieces spanning his career. The first and largest gallery features the print version Sekula made in 2011 of his Untitled Slide Sequence from 1972, a linear sequence of twenty-five photographs made on the sly (until he was ejected for trespassing) of aerospace workers leaving the day shift of General Dynamics Convair Division in San Diego. This black and white piece is for the first time interspersed with choice later figure and portrait studies in color from Fish Story (1989-1995), Freeway to China (1998-1999), TITANIC’s wake (1998-2000), and Europa (2011).

Facing the Untitled series is This Ain’t China (1974), a mixed-media performance-based work combining mock portraits of food on offer, a management diagram of efficient restaurant organization, and a group of photographs of a motley team of restaurant workers (including the young artist) contemplating going out on strike. The “China” of the title is a pun on both worker heroics inspired by Maoist cadres and the utter pretensions of the owner of a downscale pizzeria who, while dreaming of upgrades, was poised to sack Sekula and his co-workers envisioning their own pay scales and self-governance.

Dear Bill Gates (1999) joins these other two works in the main gallery with a rather elaborate piece of staging in which Sekula makes a proto-selfie in the cold waters before the cyber magnate’s lakeside mansion in Seattle, a scenario for his direct address in letter form to the rising master of the techno-universe who had recently exhibited a weakness for pricey maritime masterpieces.

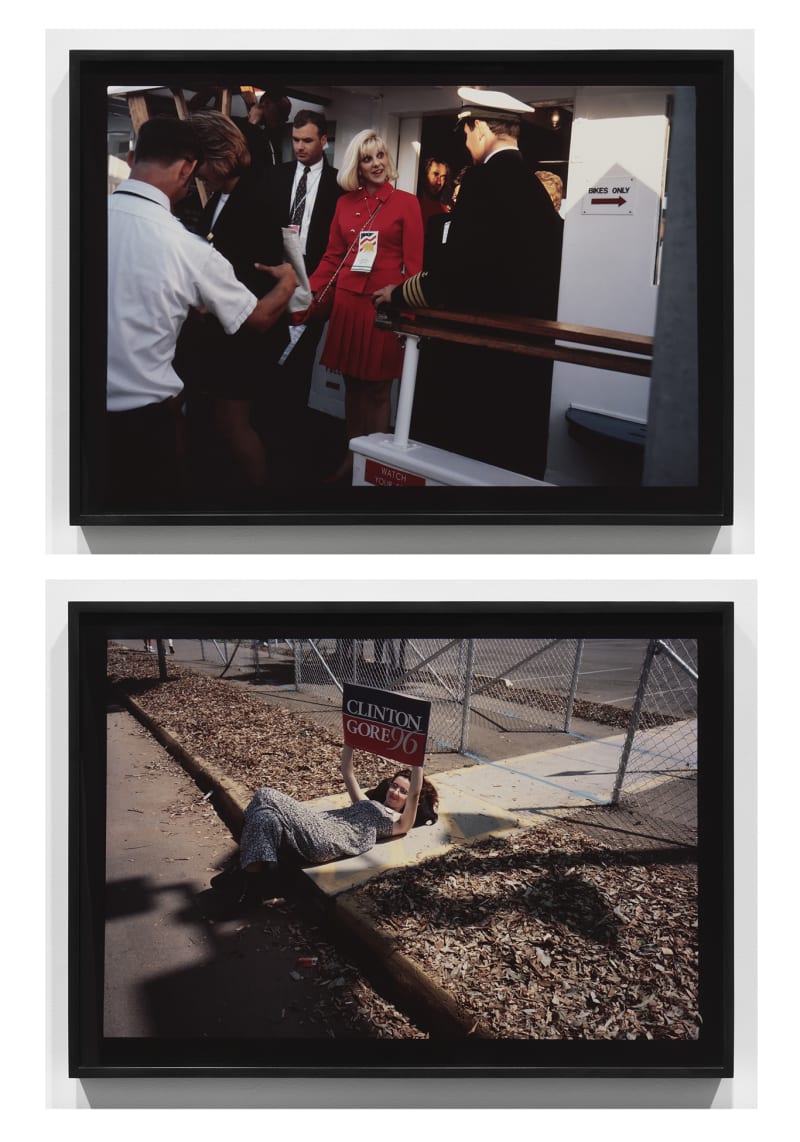

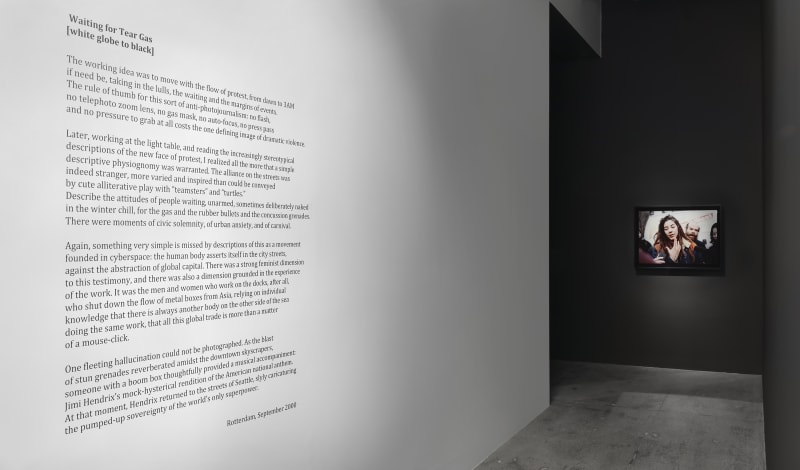

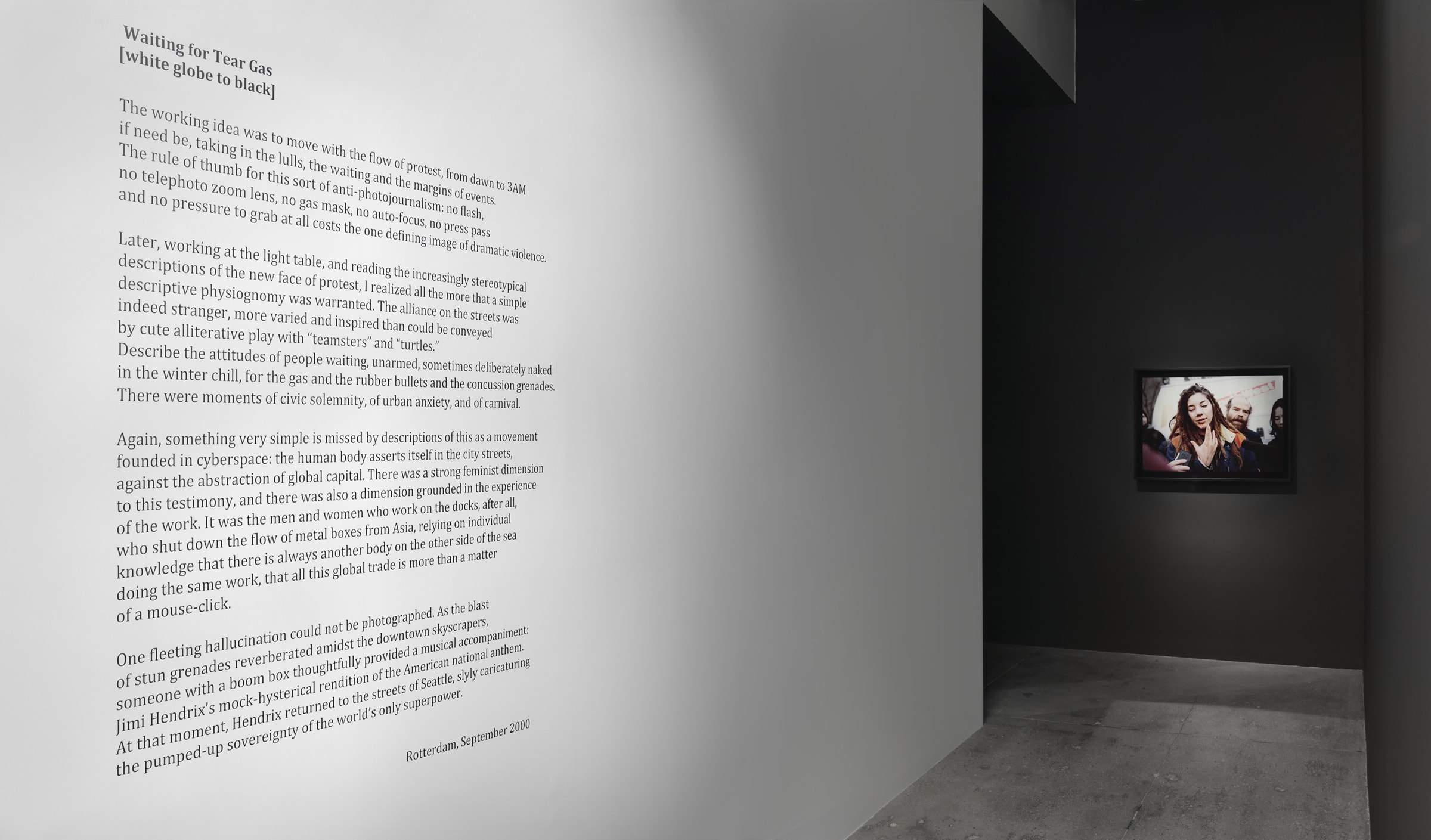

The adjacent viewing room projects Waiting for Tear Gas [white globe to black] (1999-2000), a sequential slide piece Sekula made shortly thereafter in Seattle, when he relinquished his pose as solitary aquatic stalker of Microsoft’s visionary founder, joining the Seattle street protests against the WTO just before the millennium. With a stated opposition to the photojournalist’s quest for the decisive moment by any means necessary, he opted “to move with the flow of protest, from dawn to 3AM if need be, taking in the lulls, the waiting and the margin of events, seeking to mix moments of civic solemnity, or urban anxiety, and of carnival.” In the same reflection on his modus operandi for that work, he wrote, “something very simple is missed by the description of this [massive, militant outpouring] as a movement founded in cyberspace; the human body asserts itself in the city streets, against the abstraction of global capital.”

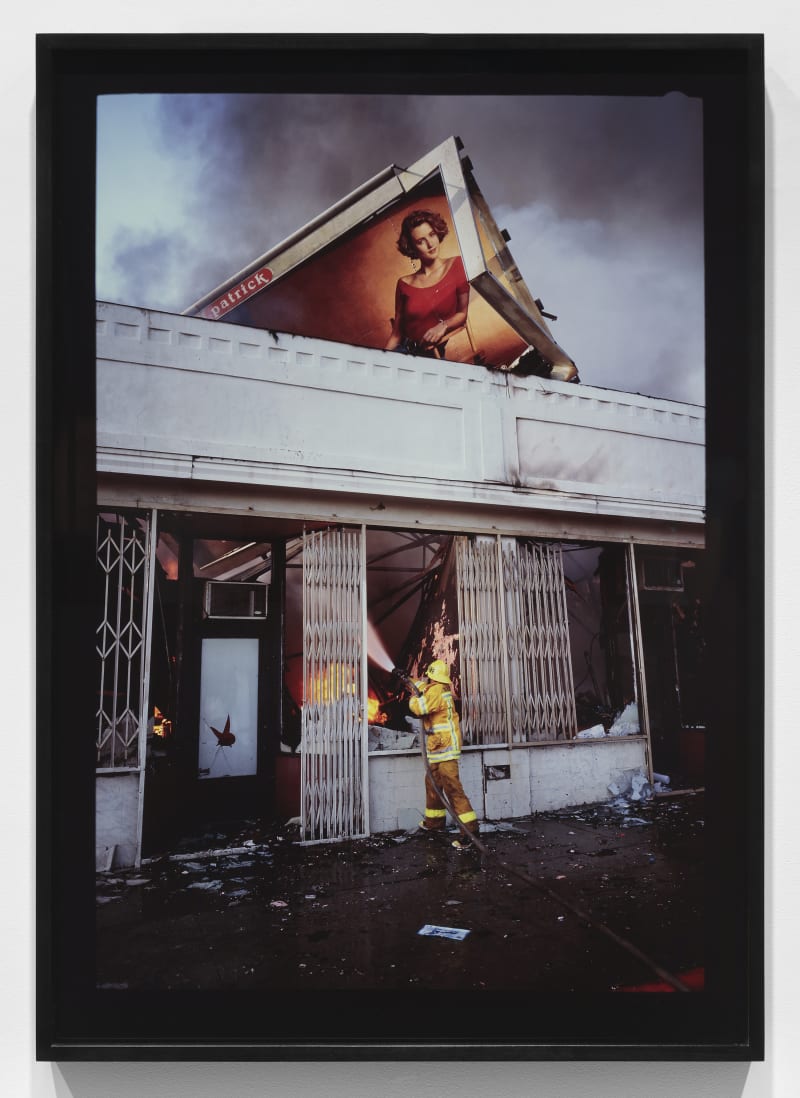

This exhibit concludes with Dead Letter Office (1996-1997) made originally for inSite, the erstwhile multi-national biennial spreading between Tijuana and San Diego. There, Sekula crisscrossed the border during the course of the failed Republican nominating convention to focus his camera on the gaps and sutures between insulated tourist culture, militarism and low-wage work in the artificial economy of Baja’s maquiladores. Drawing on Mexican traditions of ribald play with mortality, Sekula himself mines the carnivalesque by featuring the artisanal coffin workshop to revive the ghost of dead labor lurking just outside our political economy.

In keeping with Sekula’s writing about his Seattle slide piece Waiting for Tear Gas, the entire show attests to the artist’s abiding interest in figuring the working body, to better limn how work, the search for work, and the search to escape the grind of work, forms us. And because Sekula was a most eloquent artist, espousing that documentary and its dialectical criticisms must be a “literate practice,” this show offers not only much to see and savor but also to read. From start to finish, Sekula prized the trenchant value of carefully chosen words along with images, knitting them into a memorable critical tapestry to better reflect what we miss at our own risk, as thinking individuals and society as a whole. - SALLY STEIN, May 2019

Allan Sekula was an American photographer, writer, critic and filmmaker. Born in Erie, Pennsylvania in 1951, he lived most of his life in Los Angeles and the surrounding regions of southern California, earning BA and MFA degrees in Visual Arts from University of California, San Diego, and teaching at California Institute of the Arts for over three decades.

Already with his work made at UCSD in the early 1970s, both his writings and art aimed to bridge the gap between conceptual and documentary practices, focusing on economic and social themes ranging from family life, work and unemployment to schooling and the military-industrial complex. While questioning many documentary conventions, Sekula continued to see photography as a social practice, answerable to the world and its problems.

In his lifetime he earned numerous awards—National Endowment for the Arts, US Artists Fellows Award, College Art Association, Camera Austria, John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Since his death in 2013, Sekula’s library was transferred to the Clark Art Institute, his archive to the Getty Research institute, and his “Dockers’ Museum” collection of maritime artifacts to M HKA in Antwerp. His art works are in the collection of Museum of Modern Art, NY, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA); Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Art institute of Chicago; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Ludwig Museum, Cologne; Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid; Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona – MACBA; Tate London; TBA 21, Vienna; Museum Folkwang, Essen; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Stedelijk, Amsterdam, M HKA, Antwerp, among others.

Since 2013, posthumous symposia about Sekula’s work and continuing influence have taken place in Zurich (2014), Singapore (2015), Vienna (2017), and Antwerp (2017). Posthumous solo exhibitions of Sekula’s work were organized by Johan Jacobs Museum, Zurich (2014);Galerie Michel Rein (2014); Hoffman Gallery, Lewis & Clark, Portland, OR (2015); NTU Centre for Contemporary Art, Singapore’(2015); Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary – TBA21, Vienna (2017); Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona (2017); Beirut Art Center (2018), and Marian Goodman Gallery, London and New York (2019).

Please join us at the opening reception for the exhibition on Thursday, June 27th, from 5-7 pm.

For further information, please contact the Gallery at: 212-977-7160 or visit our website: mariangoodman.com.

![Allan Sekula Waiting for Tear Gas [white globe to black], 1999-2000](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_800,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/mariangoodman/images/view/9253f665c3c84f20c472b58db3ab755aj.jpg)