Overview

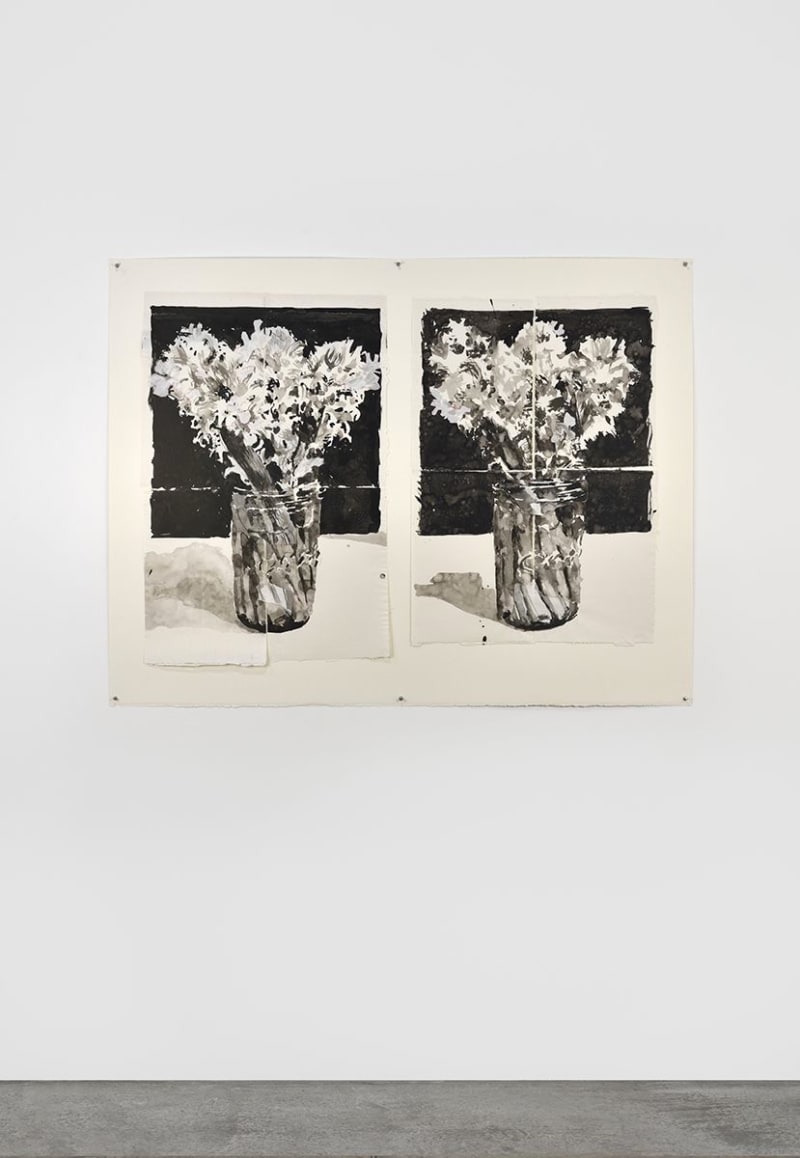

Marian Goodman is delighted to present O Sentimental Machine, a solo exhibition of new and recent works premised on William Kentridge’s abiding interest in Paris, (since he studied at l'École Jacques Lecoq in the early ’80s). It includes the major five-channel video installation that lends its title to the show, as well as four new ink on paper pieces derived from Manet’s late flower paintings and ten new portraits of historical artists, poets, psychiatrists and behaviourists, all of which have been created for the exhibition. It is the first show that occupies all three spaces at the main gallery as well as the new Librairie Marian Goodman – which contains large woodcuts from his Triumphs and Laments series – and runs concurrently with substantial Kentridge installations and performances in group shows at Fondation Louis Vuitton and La Villette.

William Kentridge: O Sentimental Machine

15 March – 15 April, 2017

Opening reception: 15 March, 6-8 PM

“I’m interested in ideas that fall apart. In what’s in the gap left when we lose our sense of Utopian thinking. And in what’s to follow.”

William Kentridge, February 2017

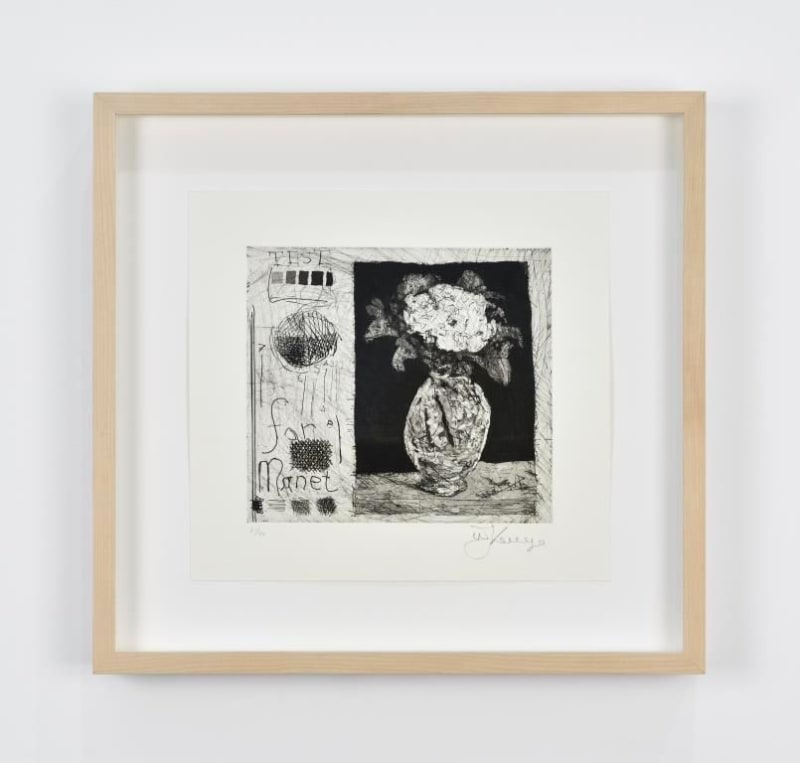

Marian Goodman is delighted to present O Sentimental Machine, a solo exhibition of new and recent works premised on William Kentridge’s abiding interest in Paris, (since he studied at l'École Jacques Lecoq in the early ’80s). It includes the major five-channel video installation that lends its title to the show, as well as four new ink on paper pieces derived from Manet’s late flower paintings and ten new portraits of historical artists, poets, psychiatrists and behaviourists, all of which have been created for the exhibition. It is the first show that occupies all three spaces at the main gallery as well as the new Librairie Marian Goodman – which contains large woodcuts from his Triumphs and Laments series – and runs concurrently with substantial Kentridge installations and performances in group shows at Fondation Louis Vuitton and La Villette.

Created for the 14th Istanbul Biennial, O Sentimental Machine was premised on a remarkable piece of film footage Kentridge found whilst working on an exhibition and opera in Amsterdam in 2015. Unable to process a visa to travel to Paris, Leon Trotsky was recorded giving the speech he would’ve delivered if he’d been granted passage to go there from exile in Turkey. Except that not even the film that was to be presented in lieu of him made it to the city, until now. After further research, Kentridge created a five-channel work, initially presented on an ample landing in a hotel adjacent to the house that Trotsky stayed in whilst in exile between 1929 and 1933 on Buyukada Island in the Sea of Marmara, Istanbul. The whole multi-layered ensemble comes alive as a ‘performance of an archive’ with other found footage of Bolshevik marches, the Tsar on a swimming holiday, as well as shot imagery of the Bosphorus and so on, surrounding the viewer in a slow cacophony across the landing.

Though Trotsky’s speech is rich in eloquent pathos, with such engrossing lines as ‘Those who believe in the words of politics are like an idiot without hope’, Kentridge assigns it a side-stage role, which in this case means a back projection through the doors of one of four bedrooms. The character who assumes centre-stage and owns the narrative of the main projection, is Trotsky’s long-suffering secretary, Evgenia Shelepina.

Trotsky had written that humans are ‘sentimental but programmable machines,’ with the qualities of semi-manufactured products that can be both fixed and edified with the correct training, maintenance and state direction. And conversely, that machines could be refined and relied on to perform complex, remarkably ethereal human activities. But he also held that both became utterly unreliable and perilously dysfunctional when either human or machine falls in love. Shelepina had begun an affair some years previously with the unhappily married author of Swallows and Amazons, Arthur Ransome, and she’s cast here in a slapstick, increasingly anarchic vignette in which her day-to-day chores start unravelling. At one point, her work environment’s chaos takes on an absurd symmetry as she performs tasks in front of an echo of her ‘other self’ behind a ‘mirror’, reminding us that The Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup was released concurrently, in 1933.

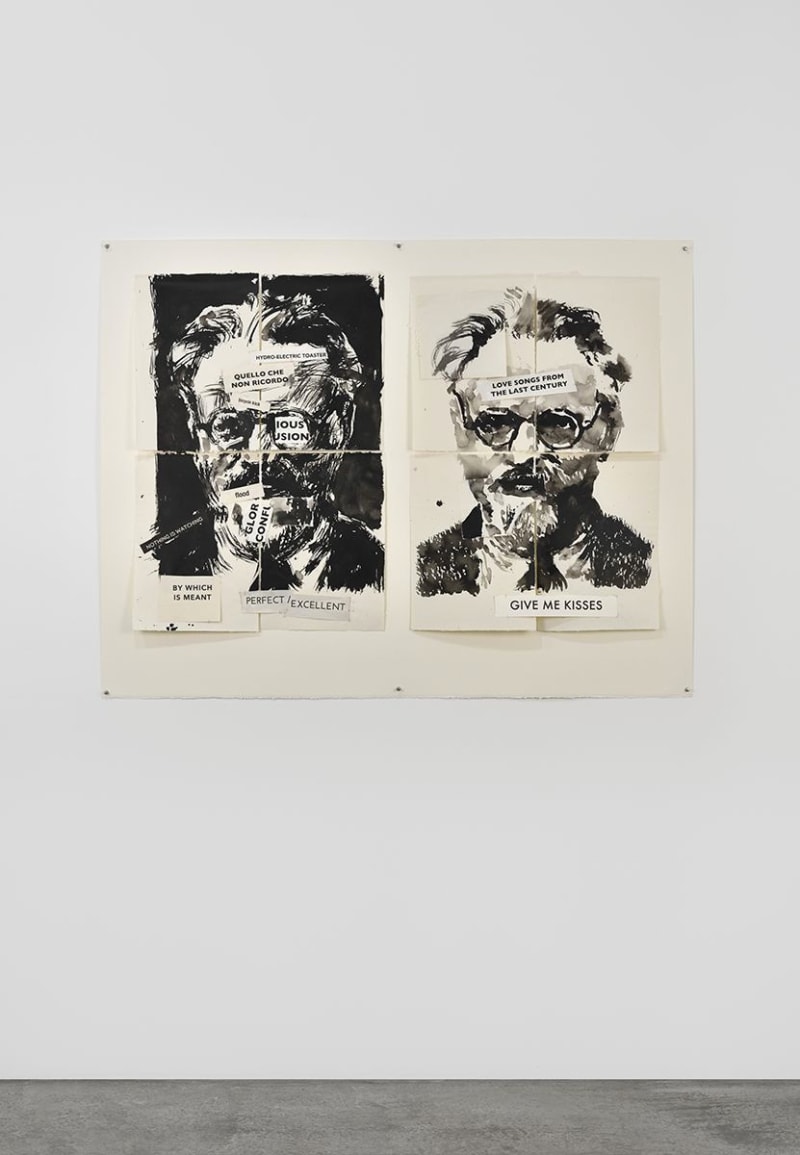

Kentridge appears as a kind of parody of himself parodying Trotsky, sporting thick black glasses, a hand-drawn beard and brows and speaking with heightened gestures. According to him, “Many Soviet thinkers were concerned as to what would happen to imperfect people in a perfect society. They asked if our emotions were mechanical, could we get rid of rid of rage and jealousy and so on which would make it so much easier for us to get along? You can see how well that went. But the counterpart is the very contemporary idea of can we teach machines to be human?”

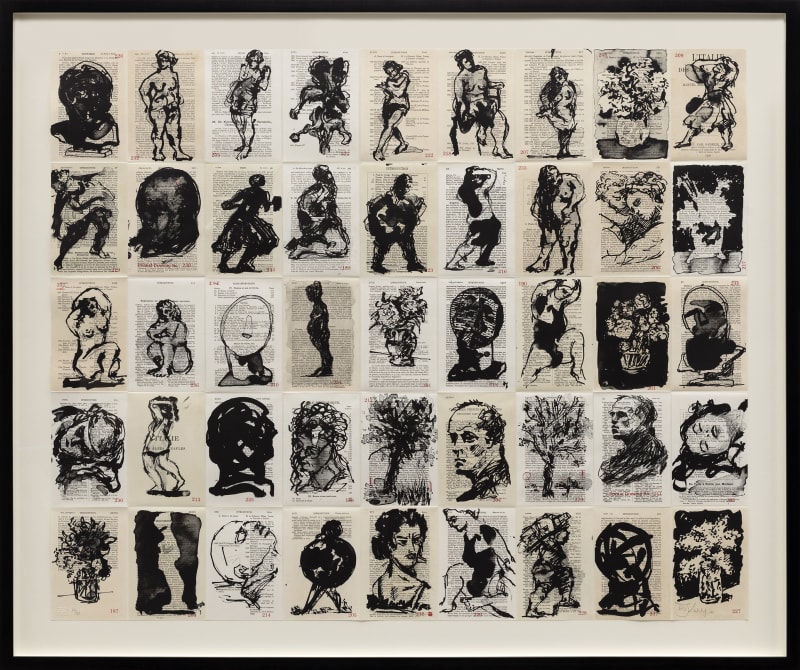

While delivering Trotsky’s speech to Paris, Kentridge wanted to create new bodies of works that also directly relate to research on the city from recent other projects, a quarter of a century since he created Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City after Paris (1989). Over the past three years he has been preoccupied by the events of both the Paris Commune of 1871 and May 1968, as well as an extended homage to Manet’s late paintings. Whilst he has developed a lasting fascination with why the man who painted the charged political work The Execution of Maximilian would devote the final years before his premature death solely to paintings of flowers in vases, this is the first time Kentridge has chosen to paint a version of Manet’s masterwork within one of his ink on paper pieces. He has also painted a series of flower works, but with hyacinths resting in Consol jars – those most ubiquitous of Southern African glass vessels, used for homemade jams, other preserves and liquids, and even fashioned into as lamps in many rural areas – and interwoven collaged texts like ‘We Also Let Blood’ beneath their blossoms.

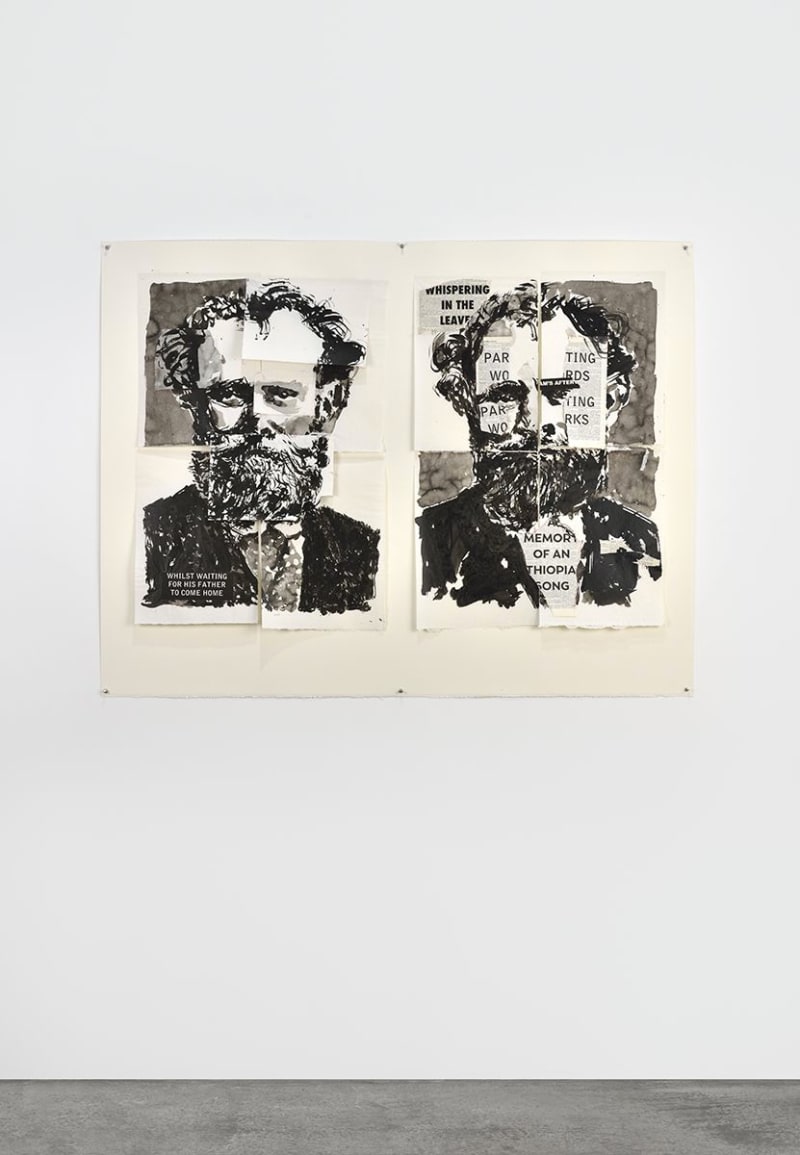

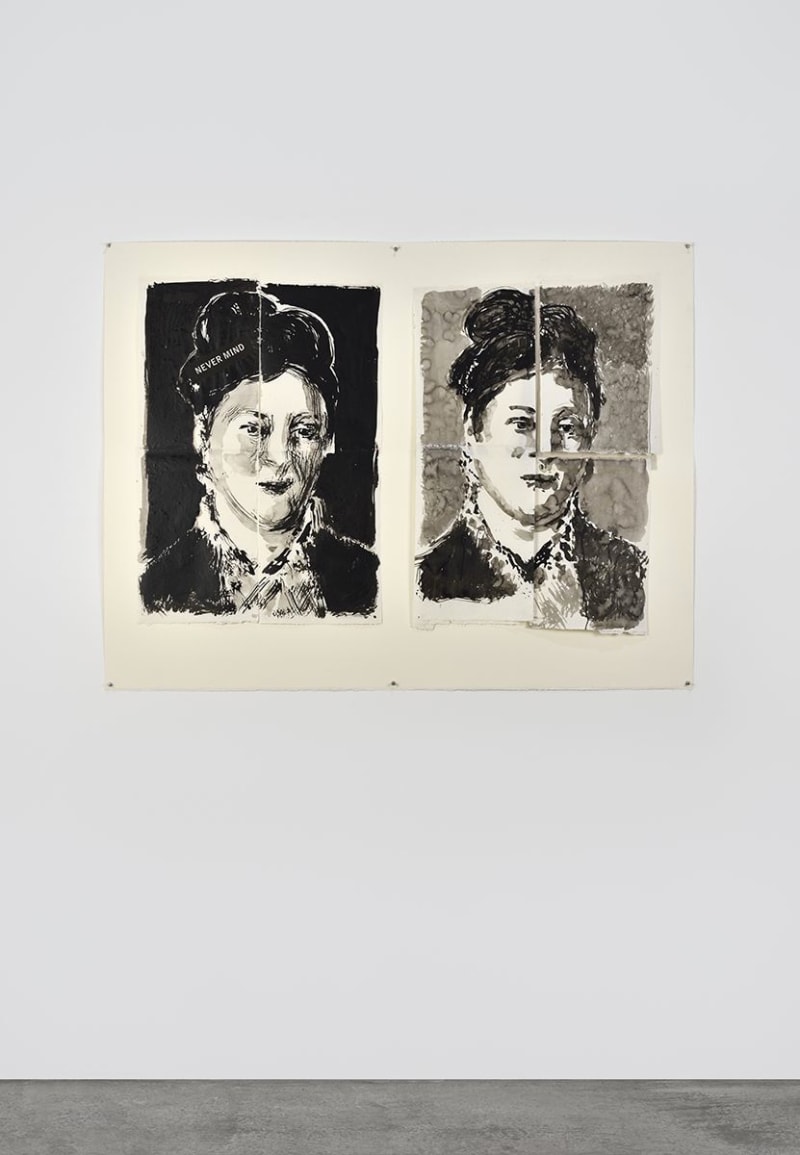

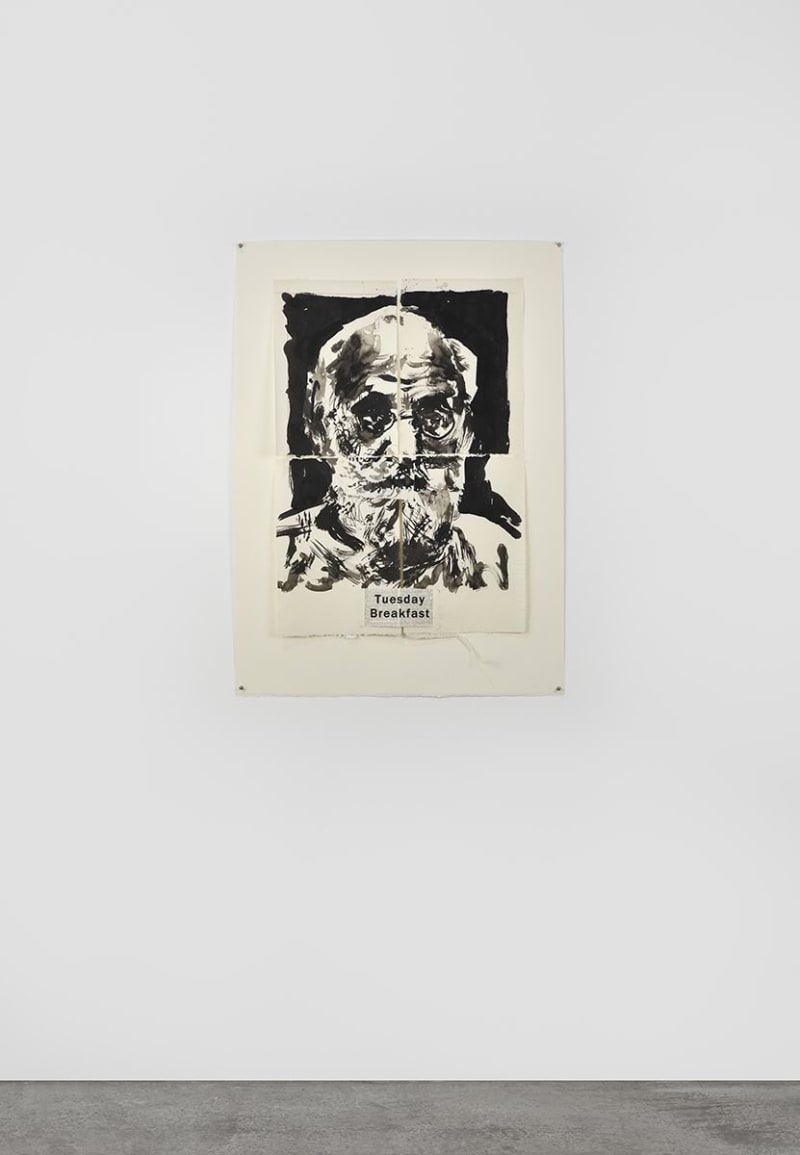

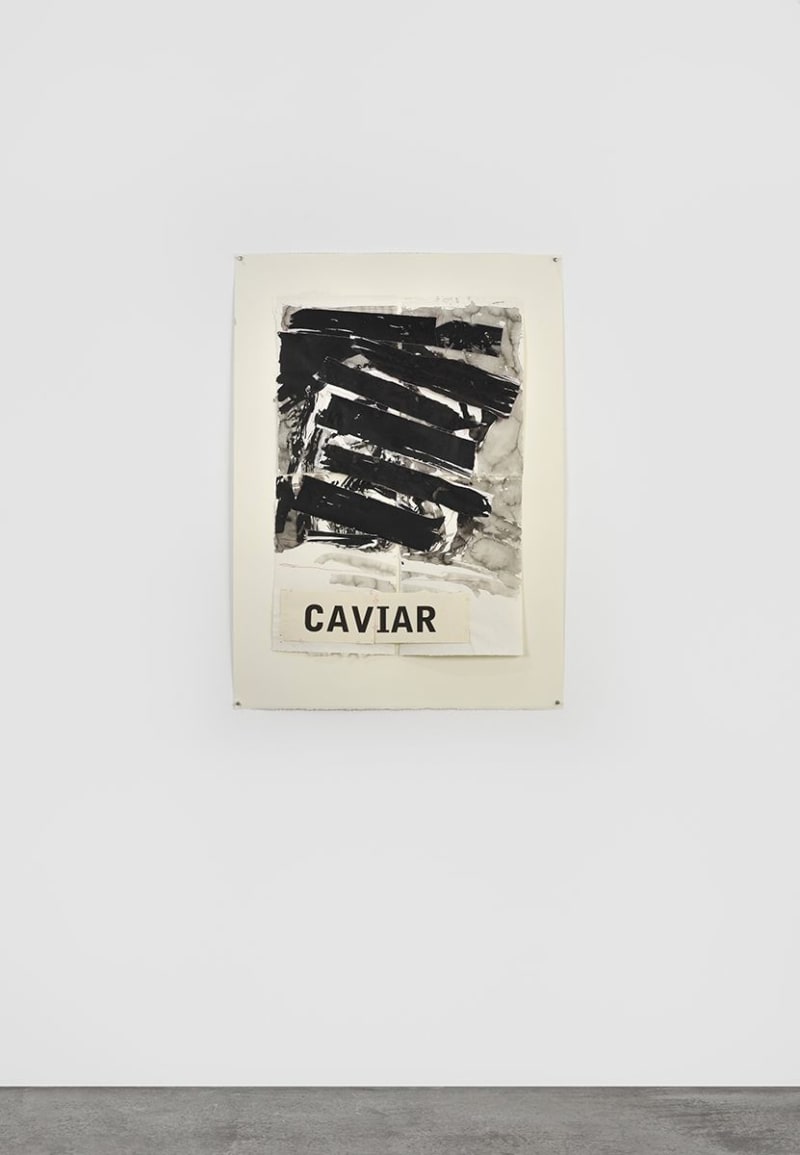

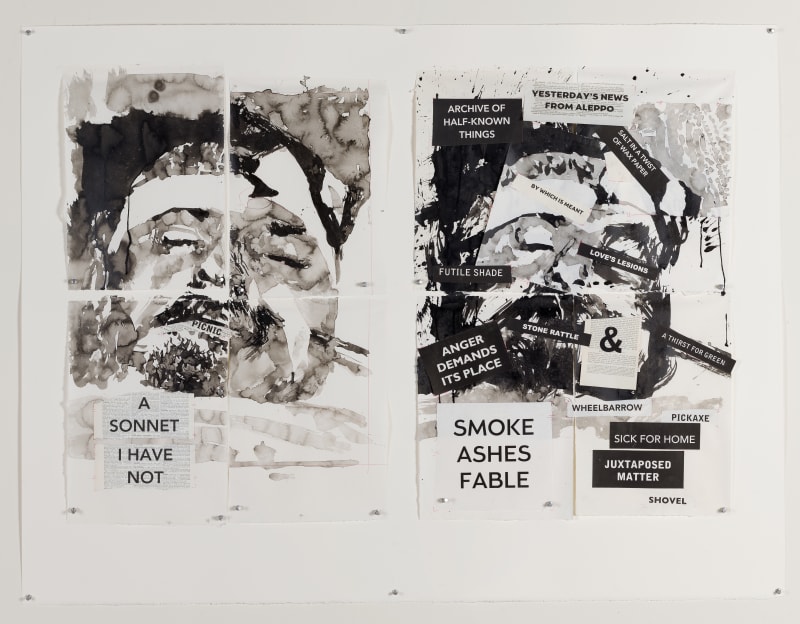

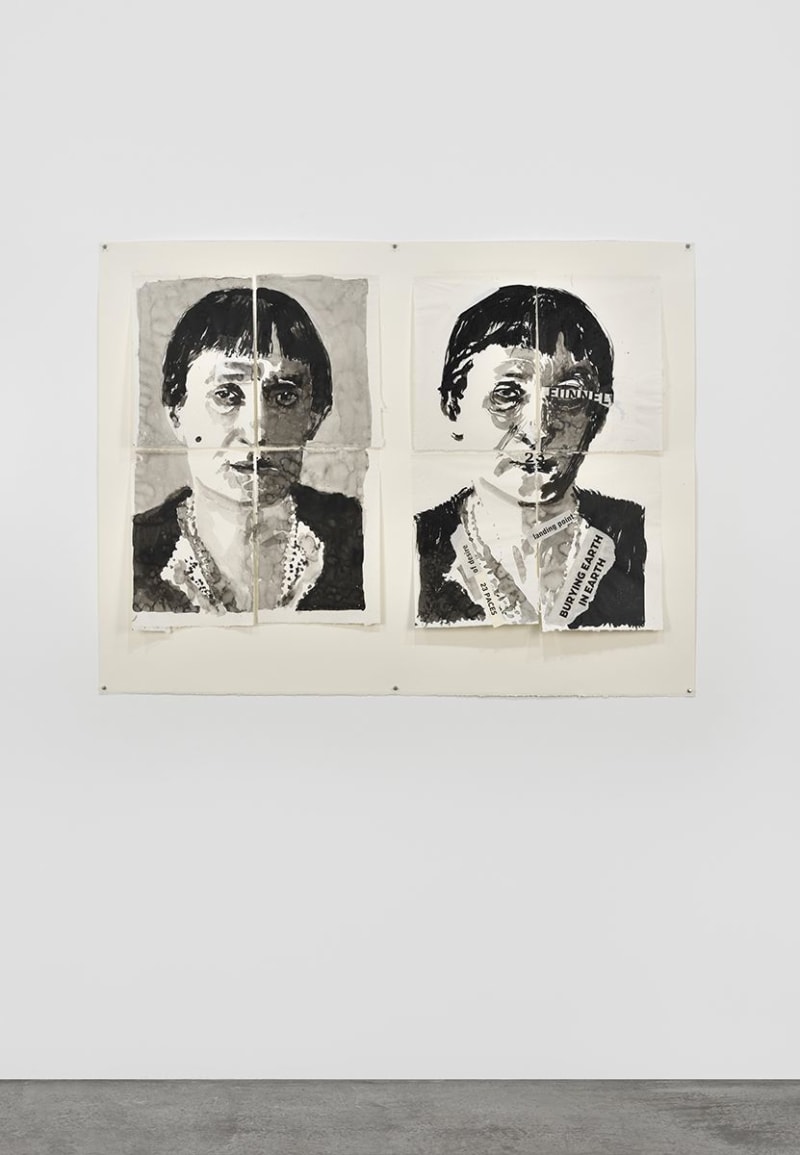

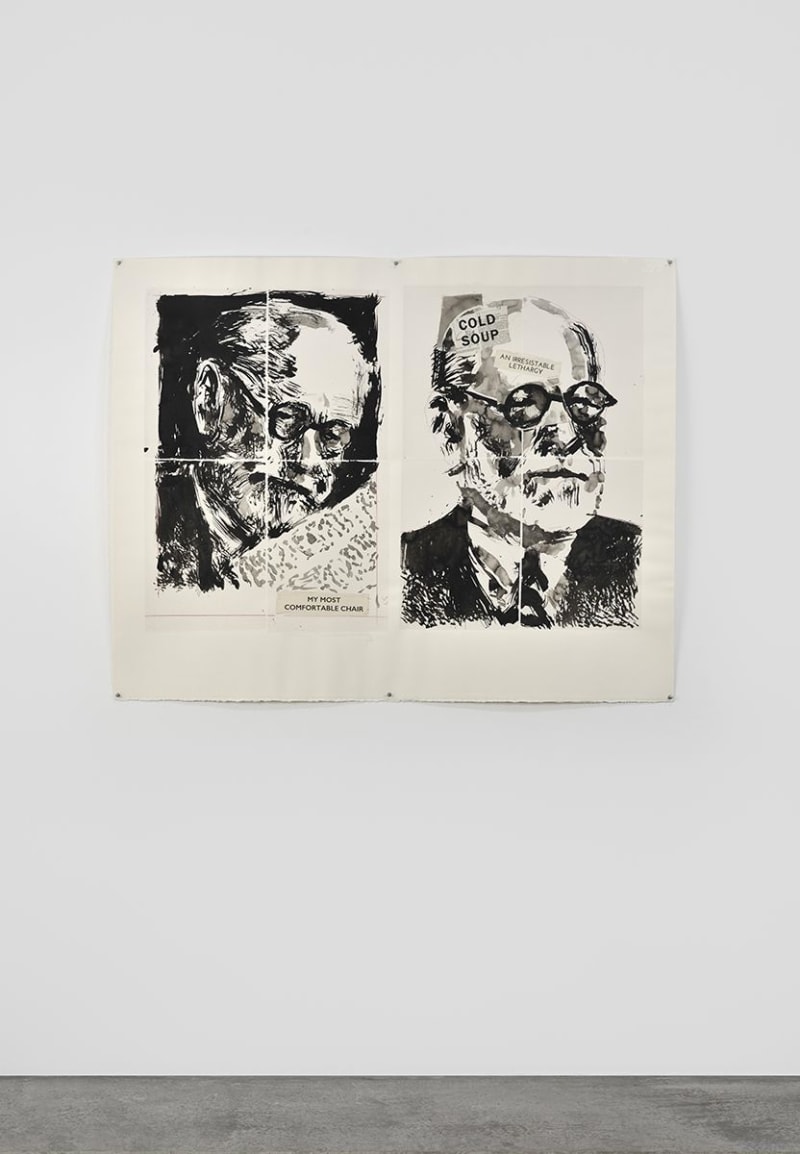

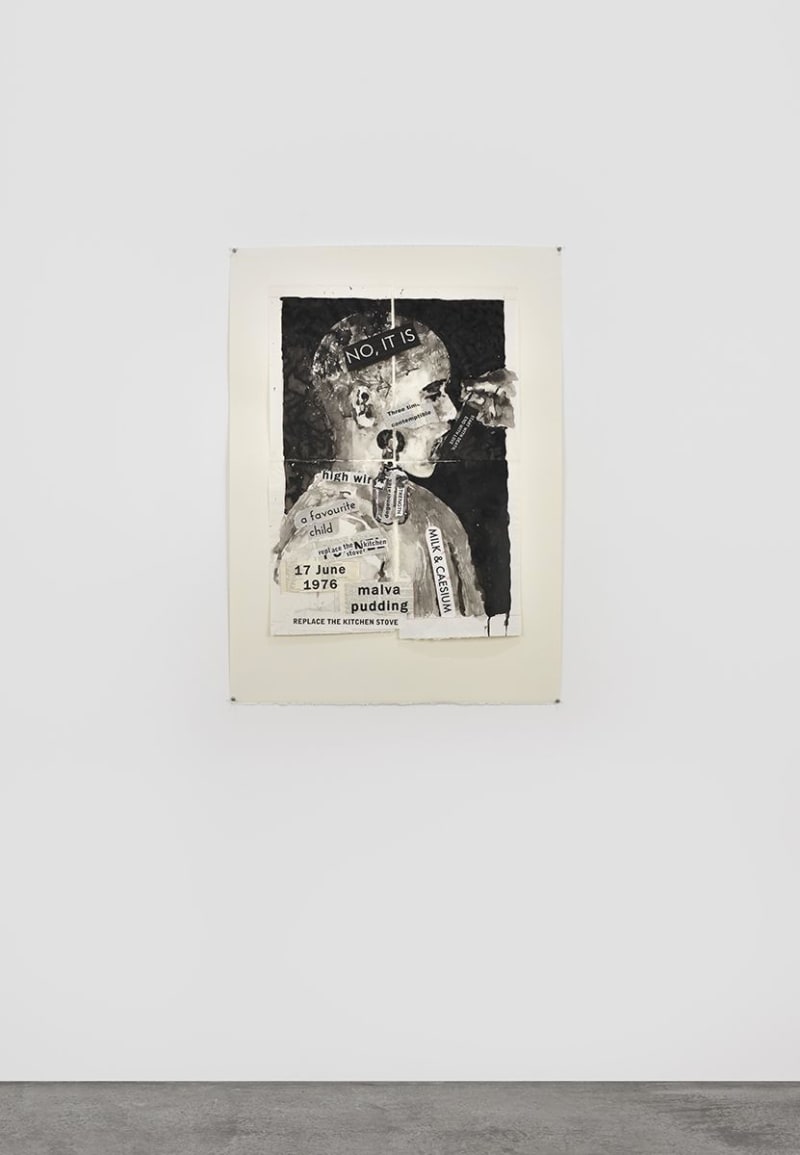

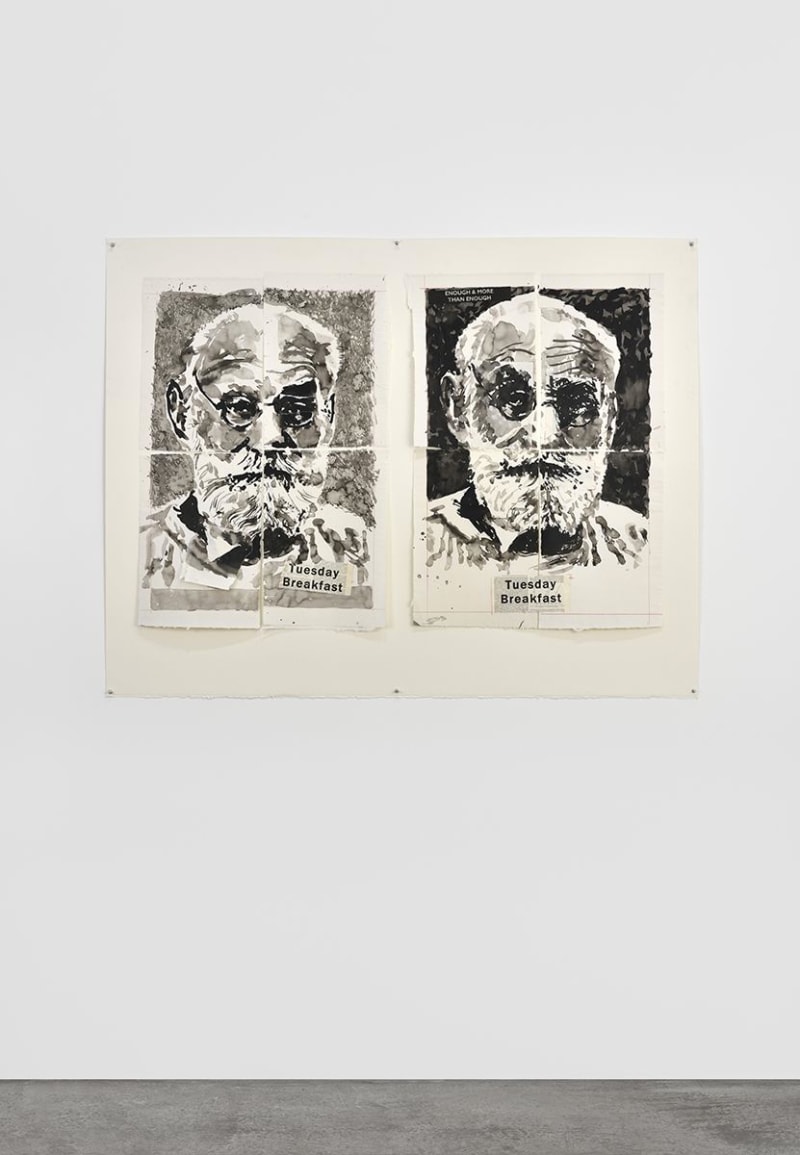

Adjacent to ‘his’ flowers, double-portrait ink and collage diptychs of Manet and his wife Suzanne divide the gallery. They give way to several portraits of early 19thC thinkers, all of whom wrestled with and argued about, in Kentridge’s words, ‘to what extent the psyche is malleable, programmable – can one dissect and dislocate it as with a series of cogs?’: Pavlov and one of his youngest patients with the day after the 1976 Soweto student uprisings beneath their profile; Freud, who was of course antithetical in his beliefs and approach; Anna Akhmatova, the Russian anti-Stalinist poet, who favoured the concrete over the mystical; and several of Trotsky himself, both in his element and immediately after his assassination. If Kentridge’s use of the word ‘Caviar’ links back to Akhmatova’s writing ¬– in that it was the euphemism Russians used for the thick black ink used by Stalinist censors – we are also reminded that, for all of Trotsky’s paranoia about White Russians in Istanbul, like Maximilian he met an untimely, brutal end in Mexico.

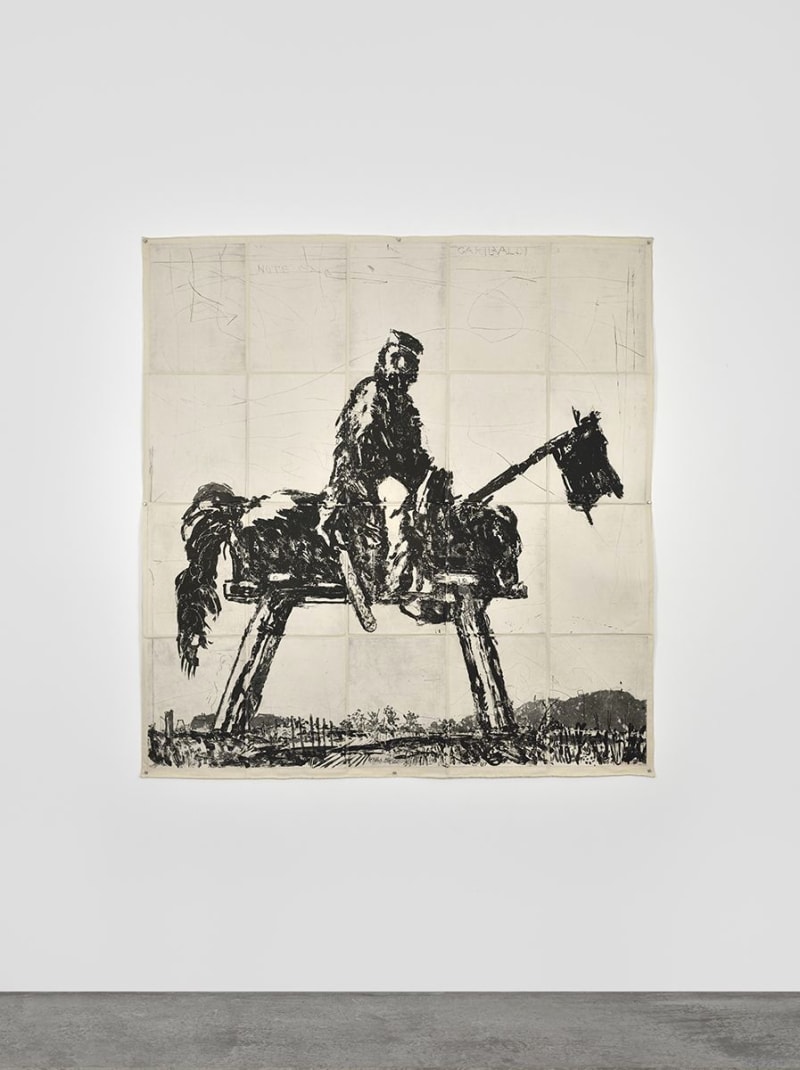

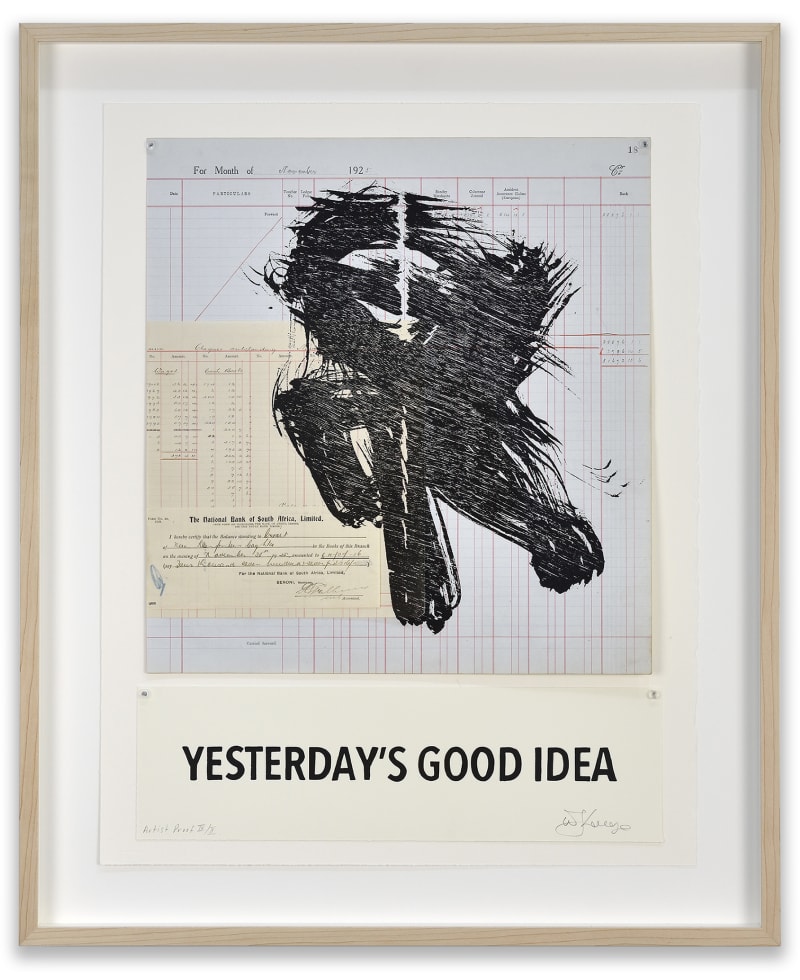

Elsewhere in the main gallery spaces Kentridge has created three large aquatint etchings on cloth from his research into Triumphs and Laments, the epic project that came to fruition last year across over 500 metres between between the Ponte Sisto and Ponte Mazzini on the banks of Rome’s River Tiber. An ignoble, vainglorious equine procession sees Marcus Aurelius atop an apparently gallant steed – which if one looks closely is in fact being pulled across the veld on a wheeled platform – Italy’s great unifier Garibaldiperched forlorn on the most rudimentary wooden horse, and a collapsing nag from a Roman sarcophagus within Trajan’s column, ironically titled Triumph of Bacchus.

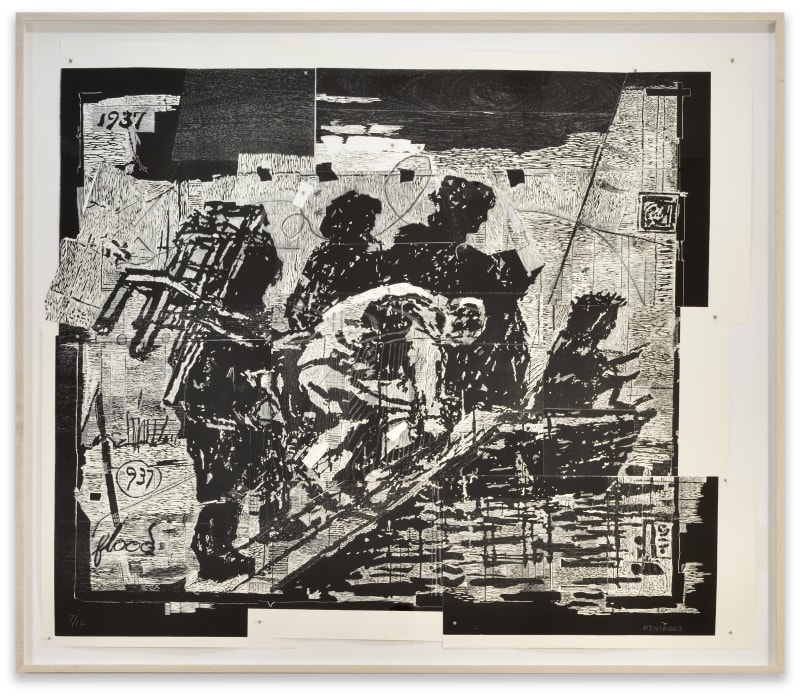

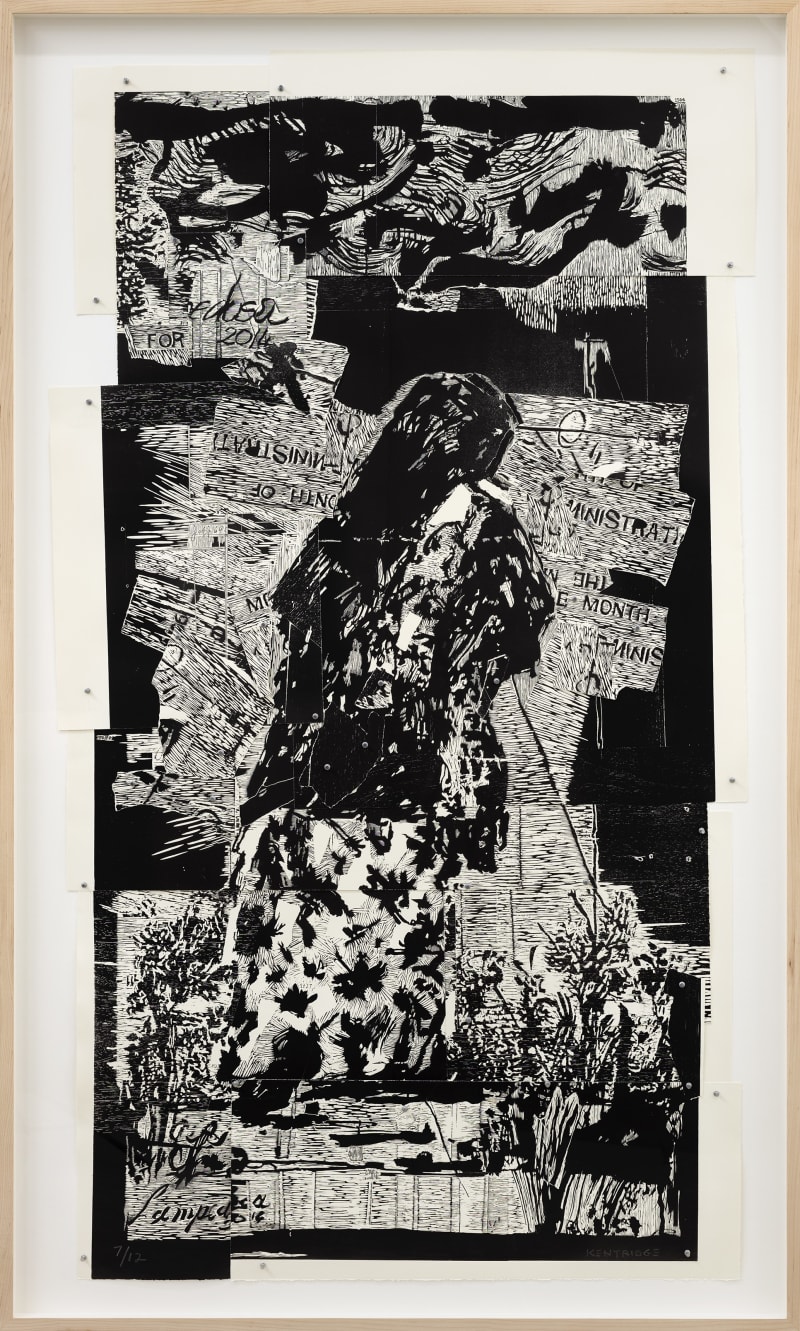

Their procession continues across the Rue du Temple as three new woodcuts, also originating through research for Triumphs and Laments, traverse the new Librairie Marian Goodman. The Flood takes us back both to the Tiber and the ’30s, as Romans carry furniture onto a perilously small vessel to escape the rapidly rising waters of 1937, while three ‘Corselet Bearers’ from Andrea Mantegna’s The Triumphs of Caesar march as if in a recent Kentridge performance. Finally, the elegiac silhouette of a lone Eritrean woman mourns members of her family who were the victims of a shipwreck off Lampedusa in 2013, reiterating that, for the myriad layers of historical cross-referencing in this exhibition, Kentridge is utterly engaged in contemporary realities.

William Kentridge’s (born 1955, lives and works in Johannesburg) More Sweetly Play the Dance will be in Afriques Capitales, La Villette, Paris, from 29 March – 2 May while Notes Towards a Model Opera is in Etre La at Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, from 26 April – 28 August, who host his Paper Music performances on 26 and 27 of April. Kentridge’s touring solo exhibition Thick Time is at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Copenhagen, until 18 June, before travelling to the Museum der Moderne and Rupertinum, Salzburg, in July, and the Whitworth Art Gallery and Manchester Museum, University of Manchester from autumn 2018. October 2017 sees the opening of two further solo exhibitions: Enough and More than Enough, at Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, and Smoke, Ashes, Fable at the Sint-Janshospitaal, Bruges.

Press contact:

Raphaële Coutant raphaele@mariangoodman.com or + 33 (0)1 48 04 70 52