Overview

Marian Goodman is pleased to present a major exhibition of new works by William Kentridge at 5-8 Lower John Street. This is Kentridge’s first substantial solo presentation in London for 15 years and includes two immersive multiscreen film installations, monumental ink-on-paper paintings, sculptures and drawings. The upper gallery is dedicated to More Sweetly Play the Dance, an eight-screen processionary danse macabre. But, beyond the medieval notion of dancing as a means of staving off death, as this 40 metre, life-sized, circular caravan traverses around us, one senses that it’s as much a cortege of those who have been deprived of a fully realised life – yet another procession of refugees fleeing a skirmish or warlord. ‘My concern has been both with the existential solitude of the walker, and with social solitude – lines of people walking in single file from one country to another, from one life to an unknown future’. William Kentridge, A Dream of Love Reciprocated, 2014

William Kentridge: More Sweetly Play the Dance

September 11 – October 24, 2015

Opening Reception: Thursday, September 10, 6–8 pm

Marian Goodman is pleased to present a major exhibition of new works by William Kentridge at 5-8 Lower John Street. This is Kentridge’s first substantial solo presentation in London for 15 years and includes two immersive multiscreen film installations, monumental ink-on-paper paintings, sculptures and drawings.

The upper gallery is dedicated to More Sweetly Play the Dance, an eight-screen processionary danse macabre. But, beyond the medieval notion of dancing as a means of staving off death, as this 40 metre, life-sized, circular caravan traverses around us, one senses that it’s as much a cortege of those who have been deprived of a fully realised life – yet another procession of refugees fleeing a skirmish or warlord. ‘My concern has been both with the existential solitude of the walker, and with social solitude – lines of people walking in single file from one country to another, from one life to an unknown future’. William Kentridge, A Dream of Love Reciprocated, 2014

Most of the itinerants are filmed holding up silhouettes transcribed from enlarged Kentridge drawings as they march: a group of priests sway past bearing a forest of lilies; patients cling to drips with sketched saline solutions barely keeping them alive; robed shadow-figures who recall pre-Quattrocento frescos hold giant classical busts, propagandist portraits, bird cages and miners’ heads (many of which are shown in the adjacent upstairs gallery); and a trio of skeletons dance on a platform dragged across the artist’s barren, charcoal-drawn landscape. An entire brass band leads the procession, and its wailing but vital, defiant anthem, while Kentridge’s long-time collaborator Dada Masilo brings up the rear, dancing en pointe with a rifle to the last strains of their canticle, as if singlehandedly “hold[ing] the hope and disillusion together”. William Kentridge, Peripheral Thinking, 2014-15

Downstairs, Kentridge presents Notes Towards a Model Opera, a three-screen film installation that grew from his research for a recent exhibition at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing. He found himself repeatedly drawn to Madame Mao’s Eight Model Revolutionary Operas, which conflated vainglorious folklore, jingoistic re-presentations of military victories, martial arts and ballet, including, as Kentridge notes, the peculiar skills of “…learning to throw a hand grenade en pointe [and] charging through the enemy machine guns en pointe…” Peripheral Thinking, 2014-15. The soundtrack for the piece, arranged by the composer Philip Miller, is based on various elaborations of the communist anthem The Internationale ranging in style from period 1950s colonial dance bands to South African toyi-toyi chanting protest marches. Masilo is here again, dancing in a cultural revolutionary uniform while wielding guns as if limbs and switching seamlessly between contemporary South African choreography and classical ballet. Her fellow cadres wave scarlet flags while torn maps, calligraphy and pages from the notebook that gave this work its title, project a constant flux of stage settings.

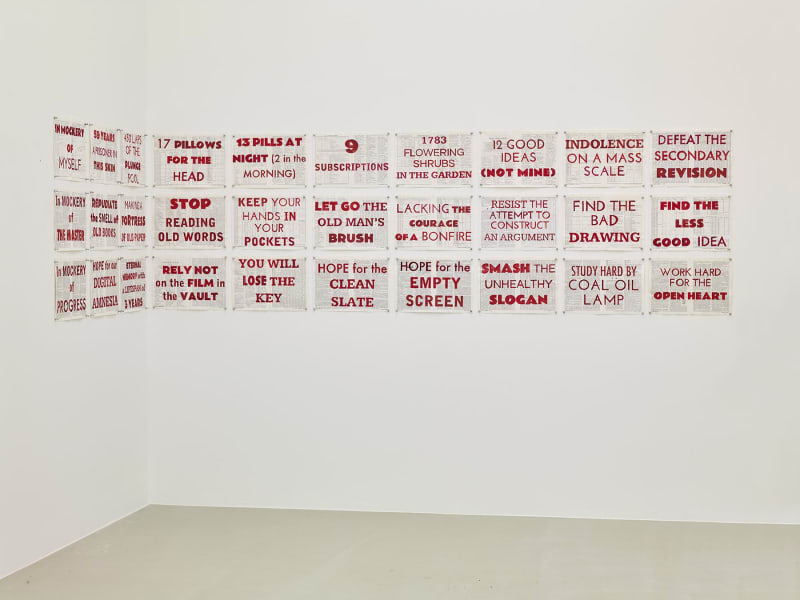

In one scene, Masilo wears a dunce’s hat and billboards covered in slogans, re-enacting the self-denunciatory public rituals that many Chinese academics were forced to endure under Mao. But even here – in contrast to the original model operas’ certainties – Kentridge’s typically implicit approach is to elucidate through peripheral associations: this humiliated professor is part Goya etching, part Dadaist performance, part contemporary African reeling from the sudden wave of Chinese economic re-colonisation of her continent. Or, as Andrew Solomon puts it in the Ullens catalogue, ‘[Kentridge]…the patron saint of ambiguity’ has again eschewed straightforward cogent storytelling for ‘seducing us with scraps of lucidity’. This love of obfuscation connects his practice directly with those of imperial-era Chinese artists, as does his blurring of language and image to Chinese literati culture as a whole. All three originated within authoritarian societies in which ambiguity and an adept use of metaphor often prove pragmatic.

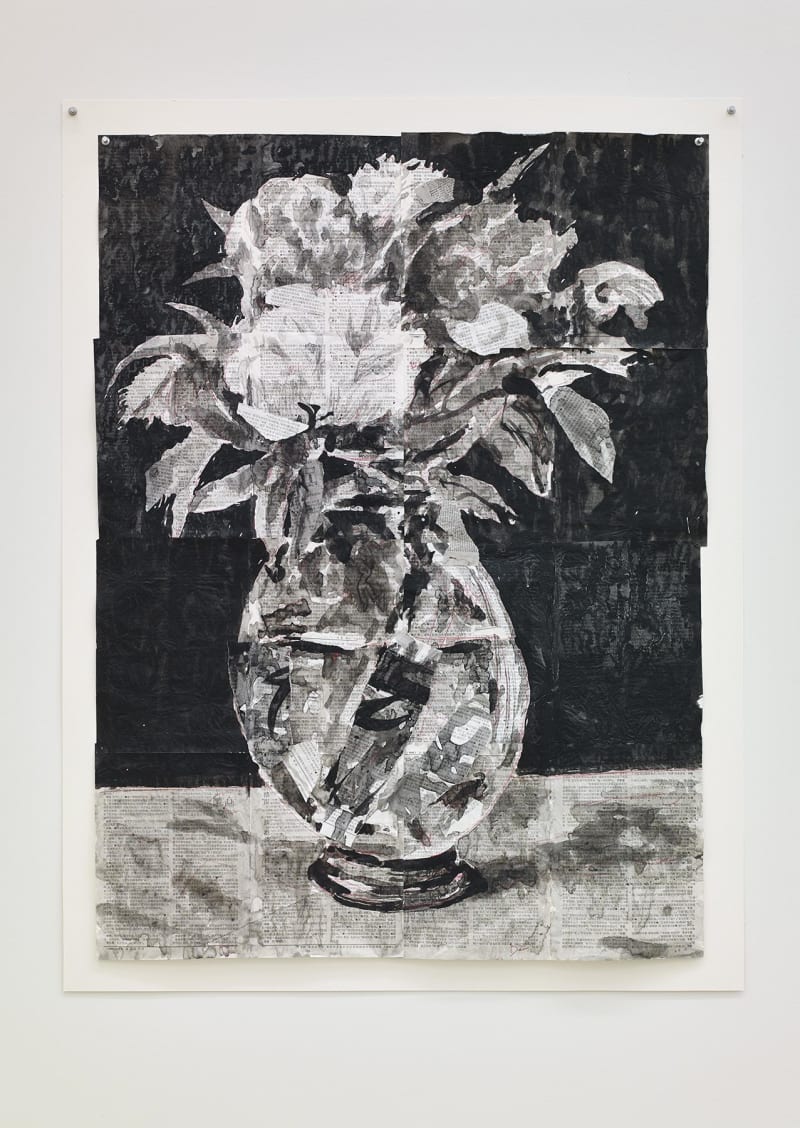

The main gallery downstairs is dominated by a new series of paintings in which generations of Chinese cultural artifacts, such as parables, Tang dynasty poetry and adapted Cultural Revolution slogans – ‘Long, Long, Long Live The Mother(Land)’, ‘Eat Bitterness’, ‘Sharpen Your Philosophy’ and ‘Defend the Rich (Harvest)’ – are interwoven throughout vast ink-on-found-text images of flowers. Beyond Mao’s now infamous ‘Let a hundred flowers bloom, let a hundred schools of thought contend’ dictum, these are premised on links between the Cultural Revolution, the events of May 1968 and the Paris Commune of 1871.

A large diptych pairs the silhouette of a single iris with a transcribed page of propaganda from the Paris Commune, which attempted to place the Communards’ daily struggles within a victorious international meta-narrative. In contrast, the leaders of the Cultural Revolution would later malign them as an ‘Imminent Probable Failure’ as they increasingly disassociated themselves from the contemporary student-led protests in Paris. Here Kentridge’s research into their delusional use, and misuse, of language abuts his abiding interest into Manet’s late paintings, and why the man who created such fervently moving political works as The Execution of Emperor Maximilian (1868–69) would devote his last years to painting solitary vases of flowers.

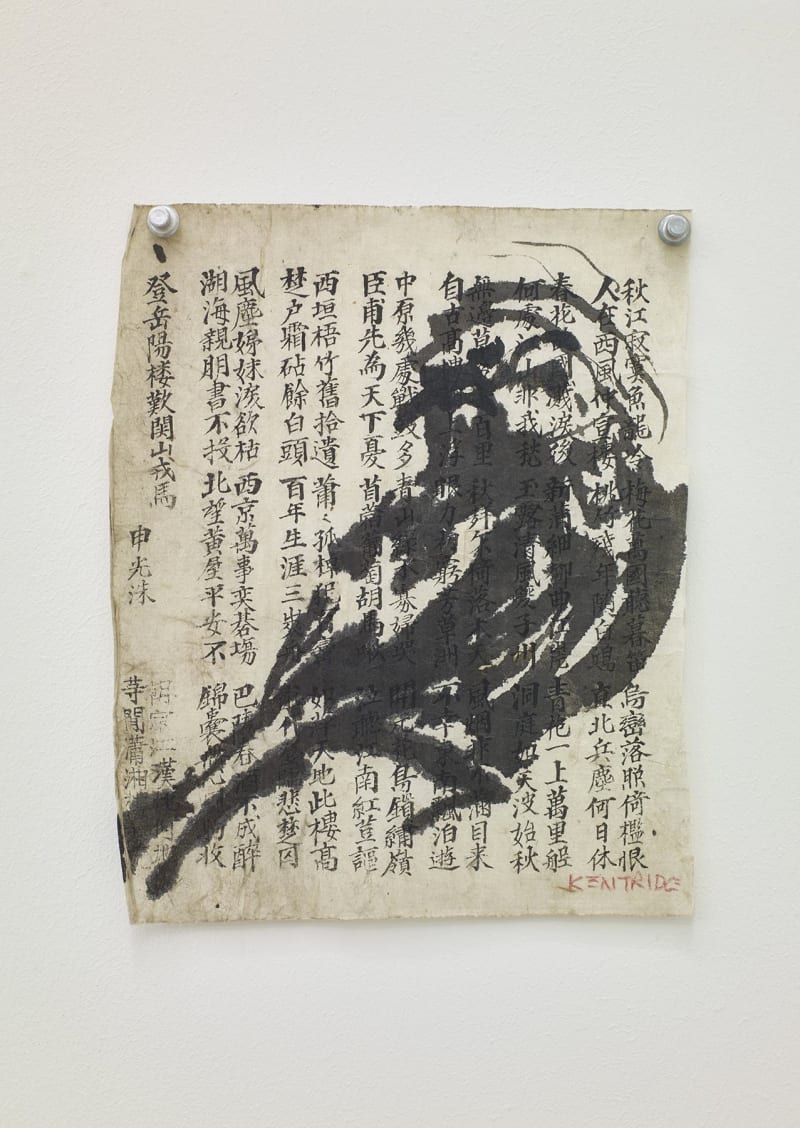

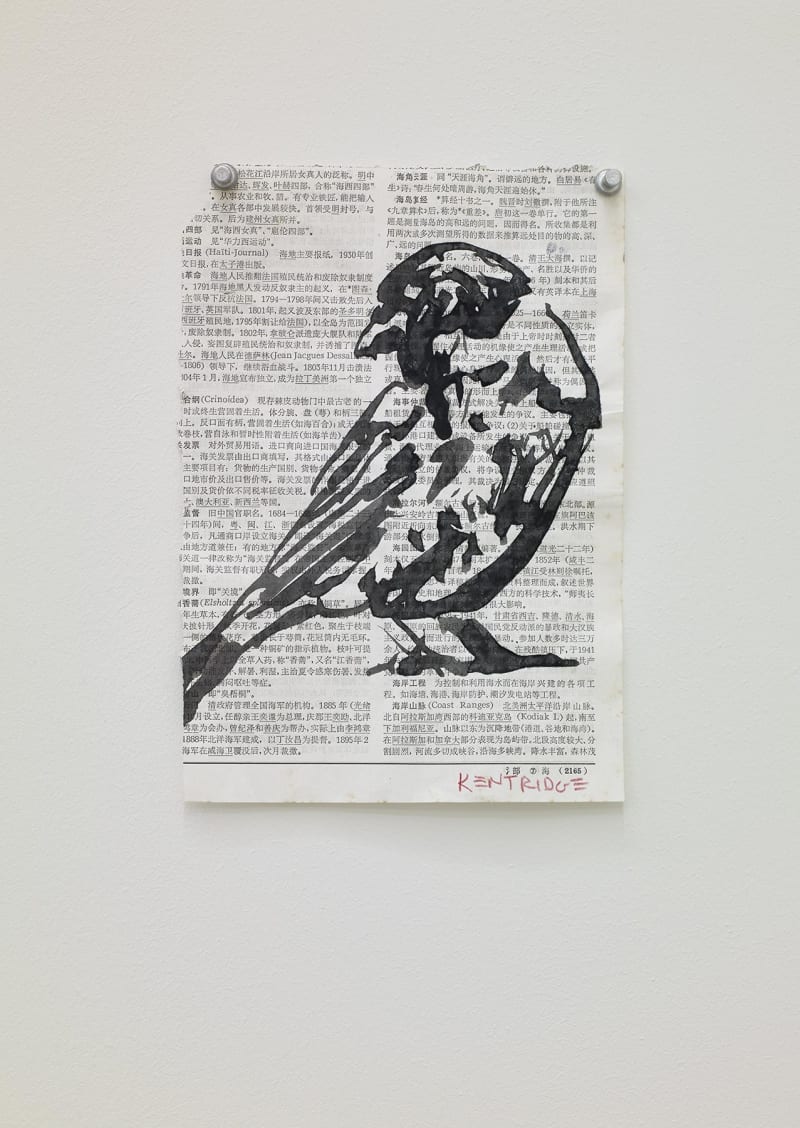

Smaller works on paper spread across two walls in the main space, including a sequence of doves flying across a sky of Chinese calligraphy and small studies of Eurasian Tree Sparrows. The latter are reminders of Mao’s ill-fated insistence that peasants should kill all sparrows, leading to the worst famine in history that followed a plague of locusts whose larvae were left uneaten – creating yet more lines of starving, subjugated people marching across barren landscapes. Suspended in a banner above them, on Masilo’s billboards, and in some ways echoing throughout this exhibition, is Kentridge’s parodied Maoist slogan, ‘Use The Wind To Rescue Speech’.

An adjacent room is bisected by two groups of painted bronze heads that originated through research for Kentridge’s production of Alban Berg’s opera ‘Lulu’. He placed cardboard cylinders over the actors’ heads, painting them with rudimentary features and creating simple masks that served as devices halfway between them and the drawings projected around them. What began as a formal investigation into how little is needed to recognise a head became adroitly bricolaged sets of five ‘Polychrome Heads’ and three ‘Roman Heads’. In addition to referring to the practice of painting over portrait sculptures in classical antiquity, each bronze head betrays Kentridge’s love of trompe l’oeil, with the materials used to construct the original – pine, fragments of Chinese maps, scraps torn from a 1906 miners cashbook, even corrugated cardboard – meticulously rendered in painted bronze. And they too point to yet another arresting Kentridge project: 'Triumphs & Laments', a 500-metre frieze on the walls of Rome’s River Tiber next year.

William Kentridge was born in 1955 in Johannesburg, where he lives and works. His work is currently a major retrospective at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, the Istanbul Biennial and Fortuna, a touring solo show in Museo Amparo, Puebla. He will be the subject of a substantial solo show at the Whitechapel in autumn next year. Lulu will be at New York’s Metropolitan Opera this November and at the English National Opera the following autumn. Kentridge has participated in most significant international biennials, including Documenta X (1997) XI (2002) and XIII (2012) and the Venice Biennale (1993, 1999 and 2005).

Marian Goodman Gallery will host a talk between William Kentridge and Iwona Blazwick, Director of the Whitechapel Gallery, in the exhibition at 10am on Thursday 10 September. Kentridge will be in conversation with Tim Marlow, Director of Artistic Programmes at the Royal Academy of Arts, at the RA from 3pm on Saturday 12 September. As part of Frieze London's West End Night, the gallery will be open until 8 pm Thursday 15 October.

The gallery is open Tuesday to Saturday from 10am to 6pm. For more information please contact Charlie Dunnery McCracken at +44 (0)20 7099 0088 or charlie@mariangoodman.com